Tranlated into English by Barbara Petersen

Dreyer was a fantastic person, but it was very difficult for him to manage his financial affairs. He went about in the film industries offering his skills and was prepared to do anything such as scriptwriting, planning, direction, or research. It was Ib Koch-Olsen from “Dansk Kulturfilm” who became aware of the world-famous director without a job. Some years earlier Dreyer had directed a short film about the organization “Mother Help”, which was absolutely no success.

To me Dreyer was “The Great Master”, whom I much admired. Therefore my feelings were mixed when I saw him coming down Madvigsallé where my place of work ”Technical Film” was. He walked into the office to talk to the manager, Knud Hjortø. But Hjortø called for me, so it became my lot to sit in the little cinema listening to Dreyer’s financial problems. He could not pay his rent, his wife was ill, and there was no end to his misery. He begged me to find a job for him. He was willing to do anything.

He also went to see Ib Koch-Olsen at “Dansk Kulturfilm”, and this time he was lucky. Koch-Olsen wanted Dreyer to make a film about the castle “Krogen” belonging to Erik of Pomerania. “Krogen” was hidden in the walls of “Kronborg”. Dreyer had now got himself a job and started with research and the manuscript. I was hired as cameraman.

The “Krogen”-film

During the preparations Dreyer had found out that it would be necessary to build a model of the castle. We went to see Poul Kanneworff at The Royal Theatre because we wanted him to build the model. We had a lot of meetings, and for the first time I got an impression of Dreyer´s meticulousness. As he did not like the construction of the roof he suggested that we ask the tileworks to produce real tiles in miniature. This would make it more realistic when we put light on it. Kanneworff got in contact with the tileworks, but it would cost a fortune to produce so many small tiles.

We started the shooting at “Kronborg” where archaeologists had unearthed a lot of ruins of the old castle which was situated inside the walls of “Kronborg”. One day we made preparations in one of the cellars to make a shot of a vault which was still intact. We were going to start at a corbel from which the ribs of the vault radiated. On the floor we had laid out rails which made it possible for us to move the camera back and follow the ribs that met in a rose in the vault. I pointed out that the picture would get better if I could use a wide-angle lens. I knew they had one at the Saga Film Studios. Dreyer wanted me to ask if we could borrow their equipment, but unfortunately it was impossible because they were going to use it themselves for the next three days. I told Dreyer who found it all right to wait for three days. I suggested that we could make some other shots in the meantime, but Dreyer did not like the idea because we had prepared to make this shot. So the whole film unit, eight persons in all, moved into a hotel and waited for three days until we got the wide-angle equipment from Saga Film. I found it a bit awkward and expensive, but it did not bother Dreyer. The result was a fine shot, which can be seen in the film “Krogen and Kronborg” (A Castle within a Castle).

Shakespeare and Kronborg

After having started the Krogen-project Dreyer got the idea to make a film called “Shakespeare and Kronborg”. The starting point should be the assumption that Shakespeare himself had been an actor at Frederik the II’s court at the castle which had given him the idea to write “Hamlet”. Koch-Olsen accepted the idea and found the money for the film. Dreyer wrote the script.

The year was 1949, and it had become a tradition that foreign companies of actors played “Hamlet” in the castle yard every summer. That year it was an American company under the leadership of Blevins Davis, a multi-millionaire. During our stay at the hotel “Marienlyst” I got to know the American actors very well, especially Ruth Ford, who played Ophelia. Ruth Ford stayed at room no 112 next to Blevins Davis. One day he asked me what I was doing, and I told him that I was working together with Carl Th. Dreyer. It left him speechless; did I really mean the Great Master? Was he 'wasting' his talent on short films? He would very much like to meet Dreyer, but Dreyer did not fancy the idea. Nevertheless a meeting was arranged during which Davis asked Dreyer about his plans for the future. Dreyer mentioned his film project about Jesus Christ, and that he could not get any further with these plans until he had made a script. He neither had the time nor the money for this work. Davis became wildly enthusiastic and was prepared to pay Dreyer for the time he needed to write the script in peace. On the spot Blevins Davis offered Dreyer a yearly pay. Thus the script was finished and Dreyer saw it as a Hollywood production. He left for Los Angeles to find out more about the conditions. At length Dreyer had got started, and it therefore was my fate to finish the film we had been working on about “Shakespeare and Kronborg”.

The Jesus Project

Some years later I met Valentine Davis in Hollywood. He was head of Paramount. He told me about Dreyer´s visit. Dreyer arrived and had asked to see the latest film productions from all the big companies. He had written down the names of the best technicians and visited the studios to choose the best technical equipment. With the “want list” in his hand he had had a meeting with the leaders of the big companies, and contrary to their usual practice they had accepted to put technology and technicians at the disposal of Dreyer’s project. Until now Blevins Davies had helped to cover all the expences. But at this point Dreyer got a new idea. He would buy a ship and sail all the equipment to Israel where the film shooting should take place. On this ship it would be necessary to build a film laboratory because one could not rely on the laboratories they had in Israel. The spoken language in the film should be Old-Hebrew.

Now Davies had enough. He withdrew from the project and stopped answering Dreyer’s letters. I had to mobilize Ruth Ford in New York. She contacted Davies who told her that he was not at all a film producer, so now others had to take over.

At some point Dreyer was contacted by Carlo Ponti. He had heard about the failed project and invited Dreyer to come to Rome and was willing to finance the film on Dreyer’s terms. Dreyer got one week to think it over and travelled back home. At that time I was in contact with Dreyer who told me that he had made a very difficult decision. He had decided to turn Carlo Ponti’s offer down. He did not want the film to be financed by Romans – the occupying power who had doomed Christ to crucifixion!

They Caught the Ferry

We met again at Ib Koch-Olsen’s office. He had got the idea that Dreyer should make a film based on Johannes V. Jensen’s short story “They caught the ferry”. I was hired as cameraman. It was a few years after the occupation, the trials against the Danish traitors and Nazis had not yet come to an end, and some of them had been sentenced to death. The Ministeriernes Filmudvalg (a governmental film committee) that was going to produce the film was part of the Ministry of Justice, so Dreyer had got an idea: If it was possible to cast one of the condemned persons in the leading part he could crash the motorcycle into a tree as described in the short story. If he survived the collision his death sentence might be altered into a milder punishment. Koch-Olsen listened attentively to the suggestion, but to me he said that it was not at all sure that the condemned person was in possession of a driving licence for a motorbike, so after some time of reflection he gave up the idea of contacting the Ministry of Justice.

Instead the professional motor racing driver Joseph Koch drove the motor bike with his wife in the sidecar. We spent a lot of time at the Nimbus garage. The ball and socket joint which was used to fasten the sidecar could also be used to fasten the camera on the motor bike. By means of long steel tubes it would be possible to fasten the camera on the outside of the motor bike and in this way make close-ups of the wheels and other details at full speed. However, the trouble was that the shots we had prepared when the motor bike was standing still were quite different at full speed.

Dreyer had got the idea that all the takes should be made at the correct speed, that is 24 frames per second. I suggested that we could change the speed of the camera till for instance 18 frames per second and thus get the same feeling of speed. But Dreyer would not at all accept my suggestion. Even if it was a close-up of the speedometer needle he wanted it to be made at the correct speed. I was really grateful that a professional racing driver drove the motor bike. Koch liked to drive fast. In the evenings we drove to Copenhagen to have the film developed, and at night we went back again. I remember once we roared across Zealand when suddenly I saw a horse carriage in front of us loaded with sharp spruce stems hanging out from the carriage. Joseph Koch did not brake but speeded up instead laying the motor bike down on the side, just able to pass the carriage at full speed. After a few kilometers he stopped the motor bike at the verge and rested his head on the handlebars. "It was close", he said, "we would not have looked well if the spruce stems had gone through us. My only chance was to speed up and lay the bike on the side. I do not hope you got nervous?". No, I was more nervous about not doing my job properly.

One day we had planned to film the motor bike overtaking a lorry on the right. I was sitting in the side car of another motor bike overtaking on the left side. We succeeded, but the solo motor bike entered into the frame a bit late. I suggested we make another attempt on our way back, as Dreyer had left to order lunch for the crew. But this time things went terribly wrong. The solo motor bike speeded up so much that the lorry driver got nervous and moved to the left where we were just overtaking. We got struck by his rear wing and started swaying. We ended up driving into a roadside tree that went in between the motor bike and the side car. Luckily I sat on my heels in the side car and therefore I was thrown up into the air, past the tree and far into a field. When I woke up I was lying in the field and saw a taxi arriving. Dreyer got out and headed directly towards the damaged motor bike to examine the camera fastened to it. Apparently it was not damaged, but I had to go to hospital and have my arm plastered. I broke some ribs and my left wrist.

It is not a good idea to change film in a so-called changing bag when one hand is out of function. Thus I made the regrettable error to put the film that was already exposed into the cassette. The next day when we made a screen test in a cinema in Assens it turned out that one roll was double-exposed. Dreyer’s comment was, “Such a thing must not happen, Mr. Roos”. No, I knew!

Dreyer’s eccentricities

At a certain time we were working as second-unit on a film which Theodor Christensen directed (I suppose it was “Citizens of the Future, 1946). This project involved visits to many Danish folk high schools. Having accommodated at a provincial hotel we normally went for a walk in the town, and I noticed that Dreyer could not stand when someone walked behind him on the pavement. Then he would stop and look at a show window with lingerie until the person behind him had passed. Nor did he like it when I opened the restaurant door to let him walk in first. One evening he asked me to come to his room where he told me that he knew very well I did it to be polite, but in the future he would appreciate if I went in first.

I remember one episode from a dinner at the hotel “Landsoldaten” in Fredericia. At that time they still had a “bell-boy” who went through the restaurant carrying a blackboard on which the name of the guest was written in case of phone calls for him. The boy rang a small bell calling out the name of the guest wanted: “Phone call for Mr. Dreyer, the inspector”. Dreyer moved in his chair: “It must be for me”. And it was. When he came back it amused him much having been appointed “inspector”.

We were going to make a shot of a child being baptized in a church, so Dreyer had found out that at Snoghøj Physical Training College there was a little church that might be suitable for the purpose. We went to visit it one morning where the fog from the Little Belt was all over the area. The principal was not at home. We walked around looking everywhere but it seemed as if the school had been abandoned. We were behind the building when I saw Dreyer’s dark figure stealing forward in the fog. All this reminded me of the final scene in “Vampyr” and spontaneously I cried out as they do in the film, “Hello, Hello”. Dreyer gave a jump, was shocked and turned round saying, “You must never do this again, I was just thinking of “Vampyr”, the feeling is quite the same”. Several times I had tried to persuade him to tell something about the making of “Vampyr”, but he had always refused to do it referring to the fact that he had been so young at that time where everything had to be a bit strange. He thought that he had grown out of that.

The première of Gertrud in Paris, 1964

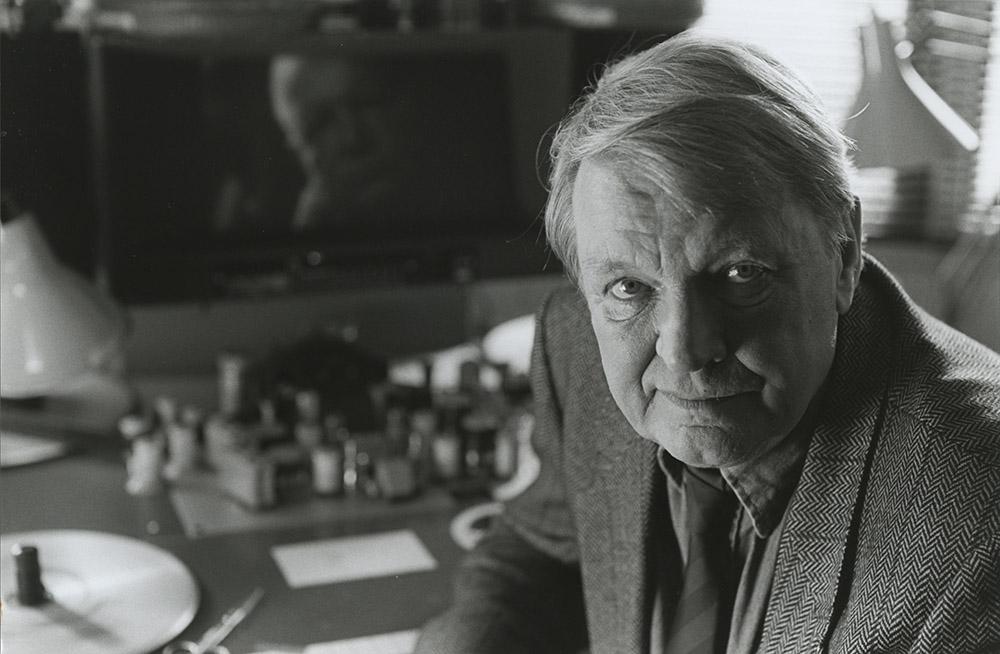

When, many years later, it had been decided to make a portrait film about Dreyer, it was again Ib Koch-Olsen who had got the idea. He talked to Dreyer who was so kind to propose me as the director. Of course I was very proud, but when the plan had to be carried out, I got the impression that he would rather not. I was permitted to meet him at the Saga Studios, where he was making some night shootings, but that alone would not do for a portrait film. The première of “Gertrud” was planned to take place in Paris, so I went by plane to Paris hoping to get something in the can. On the same plane were Dreyer and his wife. When I went up to say hello to them, Dreyer said to his wife, “This is my mortal enemy”. I hoped it would work.

A reception was held at the Danish House in Paris and every living creature was invited. Squeezed into a corner Dreyer was saying hello to the guests. I talked to Goddard and told him that I would like to make an interview with him and Dreyer. He was in if Dreyer accepted the idea. Then I told Dreyer that I would like to arrange a conversation between him and Goddard. Well, he would accept if Goddard would. So it was planned to take place the next day at eleven o’clock at Dreyer’s hotel. I arrived at ten o’clock to make preparations with the hotel but was asked to go to Dreyer’s room at once. Here he told me that he regretted having said yes, but he came up with a good idea: I could make the interview with Goddard and place a photo of Dreyer next to Goddard in the sofa. Then at home we could add Dreyer’s voice to it! I thought it was a crazy idea, so I had to call Goddard and cancel our appointment. Later I have thought to myself that the idea might not be so stupid after all, but how should I have come by a big photo of Dreyer on a Sunday morning in Paris within an hour?

My son Peter was the cameraman and we took part in all the events in connection with the Gertrud première. In the end it became too much for Dreyer, so he told Peter to stop following him. Peter was daunted and refused to film at the next event. When Dreyer saw him without his camera he said, “Where is your camera?”. Peter answered that Dreyer himself had told him to stop shooting to which Dreyer responded that he had, but nobody had said that he had to do as he was told!

We had lunch at the hotel, and in the afternoon the première took place at the cinema “Ursuline“, situated in the Latin Quarter. Dreyer’s wife wanted to come with us, but Dreyer said to her, “You better stay at the hotel, maybe there will be oproar”.

When we returned back home to Denmark I went to see Dreyer several times, but he often said that if people were interested in him as a person they could just go and see his film. As a person he was quite uninteresting. When, at length, I had heard this many times I said to him, “I’m inclined to admit that you are right, but I want something else. I would like you to tell me something about the style in your films”. He hesitated for a second. Then he said, “That I would like to do”. This was what was necessary, and I could now start to make the portrait film about him. I asked Henning Bendtsen to be present at the shooting, and Dreyer was satisfied with that.

In the following years our relationship was really good. It was always a pleasure to pay him a visit. I had found out that he liked oysters very much, so quite often I turned up with a barrel, and something told me that we were , if not close friends, then at least good colleagues.

Dreyer working with actors

Once we met at a première at the “Imperial” cinema in Copenhagen. I had a conversation with the actor Preben Lerdorff Rye, and he said to me, “Can’t you introduce me to Dreyer?” We went over to Dreyer, and I said that someone would like to say hello to him. Dreyer looked up saying, “Well, I think we know each other. Aren’t you an actor?”. “Yes, Mr. Dreyer, I played Johannes in “Ordet””.

How did this quiet, bashful man succeed over and over again in creating international film art of such greatness?

Once I talked to actor Emil Hass-Christensen’s wife. It was during the shooting of “Ordet”. She told me that Hass-Christensen worked for Dreyer, and her husband made himself still more impossible to be with. He could not sleep at night, and she was afraid that he would have a nervous breakdown. One day she said to him, “You must ask Mr. Dreyer for a talk”. The next day Hass-Christensen pulled himself together and asked for a talk. Dreyer answered, “Come to my office after the shooting”. Hass-Christensen did so and presented his problem. “Mr. Dreyer, I have now for some weeks been playing one of the leading parts in “Ordet”, but we have never really talked together. So every day I feel more and more uncertain about what I do. Is it right or wrong? Am I good or bad? What are your intentions with that part?” Dreyer looked kindly at him saying, “As long as I do not say anything, you can rest assured that what you do is quite right!”

Dreyer was an incredibly amiable person.

By Jørgen Roos

We are very greatfull to Jørgen Roos' son, cinematographer Peter Roos, for letting us publish this essay.