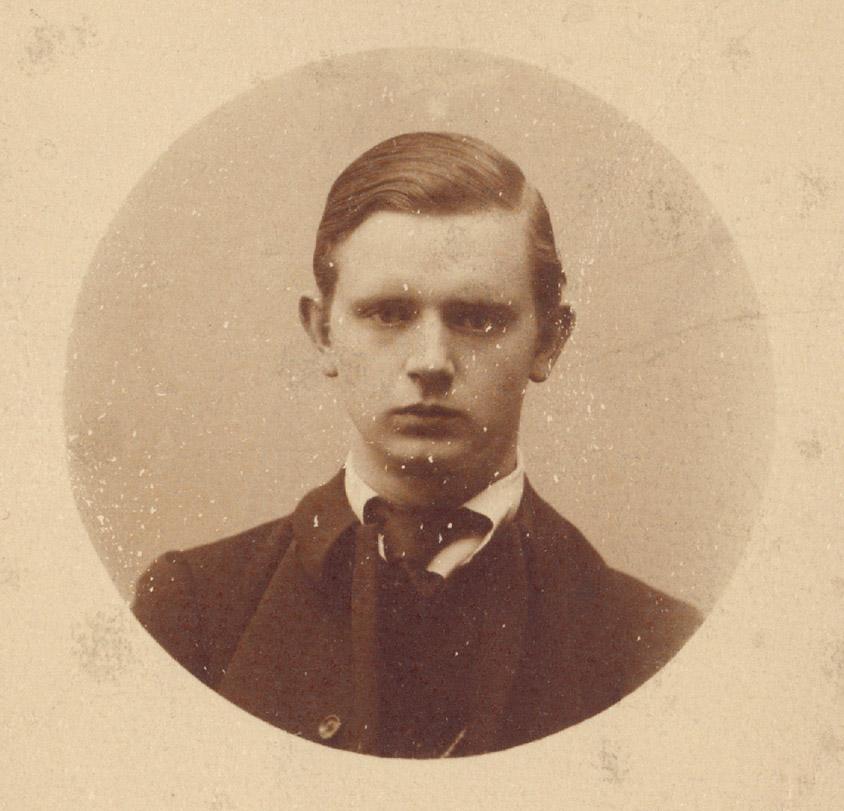

Film director, screenwriter, cinema manager. Born Copenhagen, 3 February 1889, died 20 March 1968. Married Ebba Larsen (1888-1977) in 1911. Two children: Gunni Dreyer (1913-1990) and Erik Dreyer (1923-1978).

1889: Parents wanted

Carl Theodor Dreyer was born in Copenhagen to a young Swedish woman who gave him up for adoption right after he was born. The French-Danish film scholar Martin Drouzy, in his book Carl Th. Dreyer, født Nilsson(Carl Th. Dreyer, born Nilsson) (1982), convincingly established that Dreyer was the son of a Swedish housekeeper, Josefina Nilsson, and her employer, Jens Christian Torp, a Danish landowner living in Sweden.

Because of their extramarital relationship, Josefina had to give birth in secret in Copenhagen, after which the product of the affair was given up for adoption. Drouzy moreover proves that Josefina became pregnant again the following year. She died under unfortunate circumstances on 20 January 1891 after trying to abort the foetus by consuming sulphur. She was 35 years old.

The Dreyer family

Dreyer’s adoptive father, Carl Theodor Dreyer, a typographer, passed on his full name to his adopted son. His wife Marie had a daughter, Valborg, with another man who did not acknowledge paternity of the child. The couple never conceived any children of their own. As Drouzy writes, Dreyer had a good relationship with his adoptive father but could not stand his adoptive mother. In an autobiographical sketch, Dreyer writes about the Dreyer family that it "constantly let me know that I should be grateful for the food I was given and that I strictly had no claim on anything, since my mother got out of paying by lying down to die." This choice of words reflects the grown man’s view of his childhood, though things do not appear to have been quite that bad. In one instance, the family moved him from the municipal school in Nansensgade, which Valborg had attended, to a more prestigious and respected private school, Frederiksberg Realskole. His classmates there later characterised him as intelligent and clever with an elegantly barbed and ironic wit. Marie Dreyer’s mother lived with the family and Dreyer had a very fine relationship with her. She had a strong interest in the occult and lent him books on the subject, until his parents forbid it. Dreyer took his finals in 1904. He left home soon after and, he later said, never set foot there again.

A clerk with a longing

Dreyer applied for a job and was hired by the Copenhagen Utility Company (Københavns Belysningsvæsen), but he found the work so boring that he quickly left, on 1 September 1905, for another clerical job at The Great Northern Telegraph Company (Store Nordiske Telegraf-Selskab), even then a big international company, which ignited his dreams of travel and confidential assignments. As it were, he was made to sort documents at the main office. As he later recounted, he fled from the job after the elderly head accountant showed him an old basement full of ledgers, proudly gesturing to them as his life’s work. That a similar fate might befall him filled Dreyer with horror and he resigned in early 1908. It was during this period that he met his future wife, Ebba Larsen. They were married on 19 November 1911.

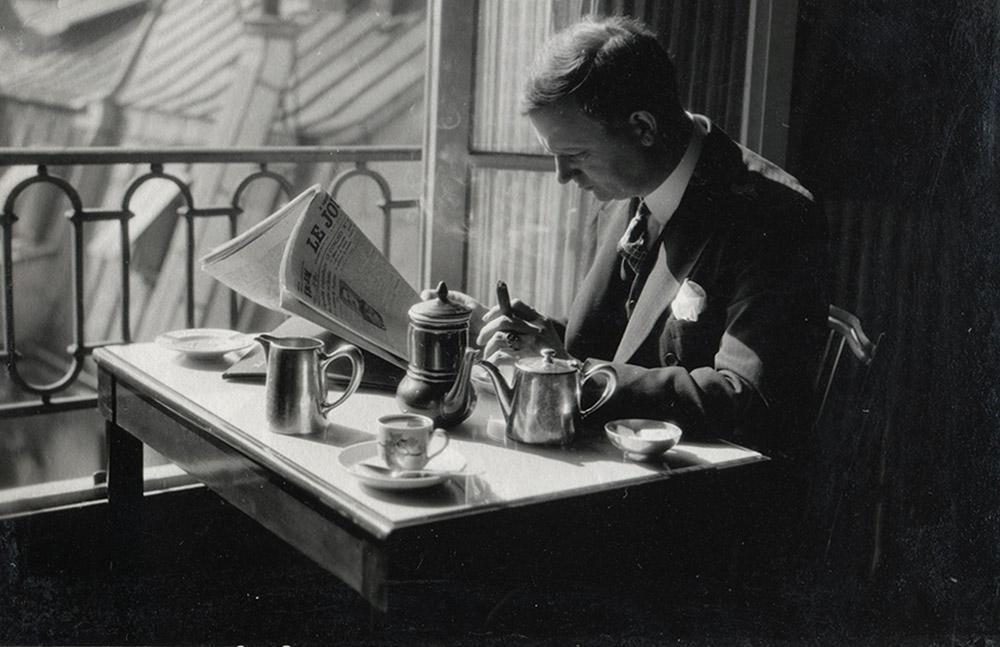

1910: Journalist and aviator

After his years at The Great Northern, Dreyer went to Sweden to seek out his biological family. He located his mother’s sister and an uncle, which is probably when he learned of his mother’s death. However, he does not seem to have stayed in touch with this family. Back in Copenhagen, he took up a career in journalism, throwing himself into this work with an altogether different enthusiasm and abandon than his office job at The Great Northern. In 1910 he was hired by the Berlingske Tidende newspaper. Among the areas he covered was the recent phenomenon of aviation. Dreyer was so fascinated that he took flying lessons himself. One of his biggest scoops as a journalist was when he reported on the first flight across the Sound between Denmark and Sweden, an exclusive for him thanks to his contacts in aviation circles. The following year Dreyer was the first passenger on a cross-Sound flight, having allied himself with the French aviator Poulain. The Copenhagen authorities had actually banned the flight, but Dreyer outfoxed them: while Poulain flew to Malmö, Sweden, Dreyer went over on the ferry and flew back with Poulain. Making the trip on a jury-rigged passenger seat under the plane between the wheels, Dreyer was subsequently described as a "young daredevil." Curiously, his image as a reporter could not be farther from the familiar image of the elderly, genteel film director, who in photographs radiates calmness and a slight air of reservation.

The same year, 1910, the newspaper Riget was founded as a national, liberal, independent paper, and Dreyer was onboard for its brief existence. He subsequently moved to Ekstra Bladet, whose sensational approach and political nonconformity was a perfect fit for him. On the pages of Ekstra Bladet he portrayed the "Heroes of Our Time," including the Danish movie star Asta Nielsen, whom he tore apart in a strikingly perfidious article: "Is Asta Nielsen-Gad a heroine? Yes, by Gad, she is! Now she has started appearing in men’s clothing without considering that she thereby reveals how dreadfully she was created. Is that not a heroic sacrifice for art?" Dreyer later spoke with great veneration about his years at Ekstra Bladet.

1913: Employment at Nordisk Film begins

Dreyer had let his interests steer him in the polar opposite direction of the prevailing norms of the Dreyer family, which valued solid, regular habits and a steady income as a secure framework for life. In 1913, Dreyer acted on his desires and in earnest took up a career in film. A Nordisk Film executive, Frede Skaarup, had noticed the young reporter who over the past year had penned four scripts for Det Skandinavisk-russiske Handelshus. Skaarup hired him to improve the intertitles for his studio’s films and Dreyer was soon assigned the job of reading and evaluating submitted screenplays. Dreyer also wrote quite a few scripts himself over his years at Nordisk, at least 31 in all, 20 of which were realised.

1918: Directorial debut

In 1918, Dreyer directed his first film, The President, based on a widely praised novel by the Austrian writer Karl Emil Franzos. Dreyer launched his career by making a film with a longer-than-usual shooting schedule plus location shooting, on the Baltic island of Gotland, which was highly unusual at the financially quite prudent studio. The film, a rather old-fashioned melodrama about the fate of seduced and outcast women, is tied together by familial and seduction relationships in a complex flashback structure, which Dreyer later deemed a failure. Still, his recurring theme of woman as victim of man’s desire and society’s condemnation shows up already in this, his first effort. Furthermore, he put a lot of energy into filling several supporting roles with the right expressive, everyday faces instead of drawing on the studio’s regular pool of supporting-role types. In addition to directing, Dreyer wrote the screenplay and handled the casting and sets – in short, he was involved in every aspect of the film.

1919: Growing ambitions

Before The President was released, Dreyer was already busy with his next film for Nordisk, Leaves from Satan’s Book (1921), inspired by Griffith’s Intolerance(1916). Here he began the practice that would become his unique working method in the future, burying himself in volumes of historical material about the period and persons that the film involved, in this case Jesus, the French Revolution, the Spanish Inquisition and contemporary, revolutionary Finland – historical situations in which Satan, in various guises, tempts man to betrayal and deceit. Dreyer had conceived the film on a grand scale, which meant it would be costly. When he asked the executives for more money for the production – 240,000 kroner in all – Nordisk balked. Dreyer had threatened to take his film to another studio but relented and finished the film within the allotted budget, which Nordisk’s management had already raised from 120,000 to 150,000 kroner.

1920: Swedish comedy with humanity and warmth

Over the next decade, from 1920 to 1930, Dreyer directed seven films produced by seven different companies in four countries, including Denmark. First he was called to Sweden, where Svensk Film wanted to work with the promising young director. Working conditions in Denmark were far from ideal for someone with his ambitions. Nordisk Film’s glory days were over and Sweden was leading the way with such names as Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller. Sjöström, in particular, Dreyer considered one of the great ones. Like Benjamin Christensen, another Danish director making films for Swedish money, though in Denmark, Dreyer accepted an offer from Sweden. Given a free hand, he elected to make a film that went against everything the Nordisk Film screenwriters’ manual had dictated, namely that the film must be set in the present, in higher social circles and in the city. Dreyer picked a story set in the past among ordinary people in the country. That is what Sjöström did and that is what Dreyer wanted to do. The resulting film, The Parson’s Widow (1921), is about a young pastor who cannot get a church assignment without first marrying the former parson’s widow, an old woman, while his sweetheart has to pretend to be his sister. The acting among these three characters makes the film a small gem of robust humour and human insight. It was always one of Dreyer’s personal favourites. The comedy genre was a new challenge for Dreyer, who seems to have thought all genres were worth a shot. The film’s atmospheric, lyrical nature photography was by George Schnéevoigt, whom Dreyer had worked with before, on Leaves from Satan’s Book.

1921: Gravity in Berlin and lightweight national-romanticism at home

Dreyer next went to Berlin, where he was in touch with a small outfit, Primus-Film. He proposed adapting Aage Madelung’s novel Elsker hverandre, which became the German film Love One Another (1922). Casting this story of a Russian pogrom, Dreyer had a perfect field of candidates among the many Russian immigrants in Berlin.

Having finished the film, Dreyer returned to Denmark, where he published a manifesto of sorts in the Politiken newspaper, New Ideas about Film. Using the example of Benjamin Christensen, Dreyer spoke up hotly for "the idealist who approaches his work with holy seriousness." He defended Christensen, who had spent two years on his film Heksen (The Witch), for pursuing his goal with unyielding obstinacy. In this writing, the outlines of a self-portrait can easily be discerned. Even so, that did not deter Sophus Madsen, head of Paladsteatret, from taking on Dreyer to adapt Der var engang (Once Upon a Time), an 1885 musical play by Holger Drachmann. It was quite a leap from harsh realism to fairytales, as Dreyer later put it in his autobiographical notes. The film was shot at Benjamin Christensen’s studios in Hellerup, north of Copenhagen, where they rented space. Dreyer later described the production as a frustrating experience and he was never satisfied with the result. If nothing else, however, the film (like The Parson’s Widow) proved that Dreyer, who had been perceived as gravely serious, was also able to make films in a lighter vein.

1924: Successful Herman Bang adaptation

In 1924, Dreyer returned to Germany, this time to work for UFA and the great producer Erich Pommer. The result was Michael (1924), based on the novel of the same name by the Danish writer Herman Bang, starring Benjamin Christensen as an aging painter who is deserted by his youthful protégé. The film got an enthusiastic reception in Germany and the Danish critics were almost as positive, though bemoaning that the film was not Danish, seeing as it was directed by a Dane, starred a Danish actor and was based on a Danish novel. Despite the rave reviews, the film was not a financial hit. Nor did anything else about it suggest that Dreyer would become Denmark’s greatest film director, deservedly ranking among the biggest international names.

1925: Big breakthrough

His next film, produced by Palladium, gave Dreyer his first out-and-out hit. Master of the House (1925), based on a play by Svend Rindom, Tyrannens Fald (Fall of the Tyrant), is an innocuous comedy about a domestic tyrant who is brought down when the role of his young wife in the household is temporarily assumed by his own former nursemaid, who tenderises him to the point where he finds himself missing his wife. Dreyer by and large maintains the simple construction of the play, while emphasising the near-claustrophobic stuffiness of the family’s small apartment. Dreyer originally wanted to shoot the film in an actual two-room apartment, but he had to let that go: the technology was too big and heavy for that to be feasible. Instead, he had a corresponding apartment built in the studio – a perfect facsimile down to the smallest details, including gas and running water. These self-imposed restrictions entailed, indeed necessitated, intimacy with the characters and limitations on camera use, creating the concentration and conciseness that became the film’s distinctive feature and also proved characteristic of the director’s future films. The film was shown to cinema managers and critics in February 1926 in Paris, where it was received with great enthusiasm and lots of press coverage. Dreyer’s international breakthrough was now a fact and the direct reason why he was subsequently invited to Paris to sign a contract with the film company Société générale de Films. First, however, he was headed to Oslo where, over a few short summer months, while the actors were on vacation from the theatres, he shot The Bride of Glomdal (1925), shooting without a script and working directly from the book by Jacob Breda Bull.

1926: Dreyer in Paris – The Passion of Joan of Arc in close-ups

Dreyer arrived in Paris in spring 1926. Société générale de Films, which preferred historical subjects, had begun to shoot Napoleon, directed by Abel Gance. Dreyer was presented with a choice of three subjects: Marie-Antoinette, Catherine de’ Medici or Joan of Arc. He consulted a specialist, Pierre Champion, who in 1920 has published the transcripts of the trial of Joan of Arc. This was the beginning of Dreyer’s extensive research into the historical material that formed the basis of his screenplay. Dreyer was determined not to make a historical film of the kind played out in grand scenes. For dramaturgical reasons, he compressed the month-long trial into a single day. The goal, as he wrote in his autobiographical notes, was to "penetrate through the gilding on the legend to the actual human tragedy – behind the artificial halo to find the actual visionary girl called Joan. I wanted to show that the heroes of history are people, too." As in Master of the House, the sets were built as whole structures, based on studies of mediaeval miniatures. Inside and out, the sets had a clear abstract shape, with windows, light sources and rooms resembling the referenced miniatures more than anything in the real world. In this film, Dreyer in earnest starts exploring the naked human face in close-ups. His demand for the un-made-up face is shown to its best advantage here. The camera captures Maria Falconetti, in the title role, until the true emotion coming from within is revealed in her face. The actors who played the priests had their heads shaved, even though their heads would be covered, and Dreyer insisted that they, too, appear without make-up.

With nearly 1,500 cuts, Joan of Arc was one of the fastest-cut films of its day. In its overall structure, the film is a quite abstract. It is not about a saint or the warrior who saves France but about Joan, a human being who will not abandon her creed and her faith and is willing to die for them. The Passion of Joan of Arc deservedly caused a sensation when it premiered in 1928. Today it is considered an absolute masterpiece of film history.

After Joan of Arc, Dreyer had a falling-out with the studio. To get rid of the headstrong Dane, they broke the contract which was for more than one film. Dreyer, for his part, took the company to court and won the suit in autumn 1931.

1930: From historical drama to hazy vampire film

After Joan of Arc and his work for Société Générale de Films, Dreyer in 1930 founded his own production company, Film-Production Carl Dreyer. The company was financed by a wealthy young film buff, Baron Nicolas von Gunzburg, on the condition that he get a role in the planned film. The rest was up to Dreyer who was now his own master. The company produced just one film: Vampyr (1932). Dreyer’s first sound film was highly unusual, a horror film employing the magic of cinema in light, sound and camera movements to create a singular, somnambulant world that can seem like a hallucination, almost unreal and just out of reach of the conscious mind. At the Danish premiere, Dreyer told the B.T. newspaper that he wanted to do something completely different from Joan of Arc, also to avoid being pigeonholed as a director of pictures about female saints. In a note to Ebbe Neergaard, Dreyer wrote that "in Vampyr I wanted to create daydreams on film and show that the uncanny does not lie in the things around us but in our own subconscious minds." The film was shot on location at an abandoned castle in Courtempierre. A few other locations were also rented, among them a mill. Apart from a single professional actor, Dreyer worked with non-actors, featuring Baron Gunzburg, under the pseudonym Julian West, as young Allan Gray.

Danish critics had respectful words for Vampyr, while also noting that it was a peculiar film for the select few. Financially, Vampyr was a disaster and, even though Dreyer at the time tried to downplay his film’s tepid reception, he had to face up to his failure. The single-minded, uncompromising director was now box office poison. During this period, Dreyer was having problems in his personal life and ended up committing himself to a clinic in Paris.

1934: Failed Africa project

Throughout the 1930s, Dreyer, undeterred, pursued different projects that all sank, some before they even made it into the water. Some made it to the screenplay stage. One film even started shooting. In 1932, Dreyer acquired the film rights to a play and wrote an outline based on it, entitled Nocturne. For another play, Monsieur Lamberthier ou Satan, which he had seen at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen, he wrote a draft of an adaptation, but that is as far as it got. The project that came closest to fruition was L’homme ensablé ("The Man in the Sand"). The story came from the Italian journalist Ernesto Quadrone who, with one Gaston Biasine, had written a screenplay, Somalia. Set in Italian Somaliland, it was more of a documentary, overlaid with a very thin fictional plot, than an actual feature. Dreyer was contacted in 1934 and rewrote the screenplay, now titled L’homme ensablé, juxtaposing nature-grounded life and civilisation in the form of natives and white colonists. Dreyer left for Somalia to start shooting, but he was unprepared for the conditions in a country so close to the equator. He contracted malaria and had to return to Denmark. A few years later the film was finished under the title of L’esclave blanc, directed by Jean-Paul Paulin of France, and barely elicited a shrug from audiences and critics.

1936-41: Life in the City Court

After the Africa project, Dreyer returned to Denmark, where the advent of sound films had replaced international silent films with national musical comedies that were a far cry from the returning filmmaker’s universe. Still, he kept writing screenplays. One, A Father, is a story defending the husband in a troubled marriage and focusing on the children as potential victims. In 1936, circumstances – that is, a lack of film work – compelled him to return to his former profession, reporting. He was taken on as a journalist at B.T., where his tasks included film reviewing. But the single-minded director had no eye for other films than his own, and after four months the paper had had enough of his disengaged and negative criticism and reassigned him. Over the next five years, until 1941, readers could enjoy his discursive reports from the city court, headed Livet i Byretten (Life in the City Court). A regular in the gallery, he reported for his readers on courtroom goings-on, big and small. He wrote roughly 1,000 articles over the years, while deferring his desire, as expressed in a 1939 birthday interview, of returning to film.

1942: Back in the director’s chair: Day of Wrath

Another three years would pass before he got his chance, thanks to Mogens Skot-Hansen, head of short-film production for the Ministerial Film Committee. Skot-Hansen, an acquaintance of Dreyer’s, wanted to help his once so celebrated countryman get started again. A short-film assignment would allow Dreyer to prove that he was able to stick to both a budget and a schedule and was not the demanding and difficult film director that rumour made him out to be. Good Mothers (1942) is a 12-minute film about an institution aiding young, unwed, pregnant women.

In this short film, Dreyer met every requirement of a professional film director, turning the film in on time and on budget. Even so, Nordisk Film, which had produced the film, was unwilling to let Dreyer direct the feature he had written, Day of Wrath. Questioning Dreyer’s "odd, precious and filmic-filmic manner," the studio considered him unable to do anything but experimental films. Dreyer then took his project to Palladium. Day of Wrath is the story of a young parson’s wife who falls in love with her stepson, who is her age, and is since accused of causing the death of her husband by witchcraft. The film was a central work for Dreyer, but he had once again made a film that failed to win over the critics.

1943: Failed chamber-play film in Sweden

A few weeks after the premiere of Day of Wrath, Dreyer left for Sweden to sign a contract with Svensk Filmindustri, the studio for which he had previously directed The Parson’s Widow in 1920. He had a notion to adapt Monsieur Lamberthier ou Satan, a play he had been working on before, but in the meantime the rights had been acquired by another party. The film he did instead, Two People (1944), was based on Attentat, a play by the German playwright W.O. Somin. His second collaboration with the Swedish company was anything but happy. The chamber play – about a couple in crisis over the course of a single night in their apartment – held the stylistic challenge Dreyer was after, but the studio had a lot of opinions of their own regarding the film’s form, casting, editing, music use, etc. Dreyer personally was sceptical about the project in advance and in later years he would have liked to strike it from his filmography. At any rate, while he was alive, he did not want the film screened as part of his oeuvre. The reception of the film was exceptionally negative and led to mutual public denunciations by SF head Carl Dymling and Dreyer.

After this negative experience, Dreyer got in touch with another Swedish film company, Luxfilm. With the Norwegian writer Sigurd Hoel, he wrote the screenplay for Därför dräpte jag, based on Max Catto’s They Walk Alone, the story of a widowed minister who hires a young single woman as a nanny for his children. At intervals, three young men are murdered and suspicion falls on the nanny, even more so when one of the minister’s own sons is murdered. This project appears to have advanced quite far – preparations for the exterior shots had begun and an architect did sketches of the parsonage interiors – but a few months before the end of the war, work on the film apparently stopped, and Dreyer and his wife Ebba returned to Denmark.

In Sweden, Dreyer, himself a former balloonist, had also been working on a documentary project about S.A. Andrée’s ill-fated attempt to reach the North Pole by hydrogen balloon. In 1982, Jan Troëll used the story in his film Ingenjör Andrées luftfärd (Flight of the Eagle).

1945-1955: A decade in the service of short films

Returning to Denmark, Dreyer got back in touch with the Ministerial Film Committee, now under the leadership of Ib Koch-Olsen. In 1948, he was more regularly employed by Dansk Kulturfilm, where he worked on a number of films. Some he scripted, one he edited and eight films he both wrote and directed. No labours of love, this was bread and butter work, and it kept him in the service of film.

At the same time, Dreyer was working on several other projects. Some became screenplays, others remained just sketches or outlines. He went a long way with his 152-page screenplay for Kronen (The Crown), the story of a woman who marries a ne’er-do-well who deserts her and his role as father. Amerikas første Opdagelse (The First Discovery of America) was based on the Icelandic sagas of Erik the Red, concentrating on the fifth voyage which is led by Eric’s daughter and ends in a bloodbath. He also had plans to adapt Jørgen Frantz-Jacobsen’s novel Barbara, about a Faeroese parson’s widow with a powerful erotic attraction. Moreover, he merged two plays by Marcel Pagnol, Marius and Fanny, into one film. The story, set in the US, is about a woman torn between two men. Dreyer intended to shoot the film in a real town, without sets or actors, on the backdrop of the real world and using a cast of ordinary people.

The grand projects: Mary Stuart and Jesus of Nazareth

Dreyer poured the most energy and enthusiasm into his project about Maria Stuart. The idea for the film originated with Film Traders Ltd. of the UK, which got in touch with Dreyer after the British success of Day of Wrath. Dreyer, who took on the Maria Stuart idea with the intention of making an epic, worked intensely on the screenplay for six months, doing his notoriously painstaking research into source materials – what made Koch-Olsen of the Ministerial Film Committee call him a "documentarist." The 241-page script was never realised, however. The British company shrank at the prospect of a production on that scale which would be exceedingly difficult to finance. Later, in the early 1950s, Dreyer got the idea for a film about the painter Paul Gauguin, with a theme along the lines of his failed Somalia project. Dreyer likewise saw Gauguin as a man torn between two cultures and two women, white Nordic Mette and a subconscious longing for women of colour.

Finally, there was Dreyer’s project of a lifetime, a film about Jesus of Nazareth. He got the idea shortly after he made his Joan of Arc film. The screenplay describes Jesus the man. Like Joan of Arc, it would be about the person, not the myth or the future saint. Dreyer in 1949 got in touch with an American tycoon, Blevins Davis, who was in Denmark with a theatrical troupe performing Hamletat Kronborg Castle. Davis responded enthusiastically to Dreyer’s Jesus project, and they signed a contract. Though it became clear quite early on that Davis did not intend to honour his side of the bargain, Dreyer kept pushing ahead on the project and felt a connection to Davis, even as the American was proving to be increasingly unreliable. Dreyer taught himself Hebrew, made a research trip to Israel and studied sources at the British Museum. As he wrote Ebbe Neergaard in a letter, "every scene appears in my consciousness as a finished piece of sculpture. I know how every scene should be done." In 1967, the year before Dreyer died, the Danish state and Minister of Culture Bodil Koch decided to fund the film with three million kroner, a tenth of the film’s estimated cost.

1952: License to the Dagmar Cinema

Dreyer had become financially secure years before, in 1952, when he was awarded the license to the Dagmar Cinema. Before 1972, operating a cinema required a license and no one was allowed to operate more than one cinema. The underlying idea was to foster and promote diversity in the selection of films in cinemas, and the licenses were typically awarded to filmmakers who had distinguished themselves in their profession. After the Liberation, Dagmar was one of Copenhagen’s most prestigious cinemas, showing a culturally oriented range of films. In his years as cinema manager, Dreyer ran 240 films, including more than 150 American films. He upheld a standard of quality, screening artistic high fliers as well as robust entertainment. Thanks to this job, he no longer had to struggle to make ends meet, as had been the case for years. He ran Dagmar until his death in 1968 when he was succeeded as manager by the film director Henning Carlsen.

1954: The Word

While running the Dagmar Cinema, Dreyer directed his last two films. The Word, in 1954, was based on a play by Kaj Munk, which Dreyer had first seen in 1932. Adapting the play, which deals with the possibility of miracles, Dreyer shifted the emphasis from that aspect to the characters. Personally, he sought to explain the miracle by way of parapsychology, referring to a world beyond the known world. Again, Palladium produced. The Word was a rare hit for Dreyer – well helped by the popular name of Kaj Munk, who gained martyr status after he was assassinated by the Germans during the Occupation. The film also did well internationally, taking home the Golden Lion from the Venice Film Festival.

1964: Recognition at last – Dreyer makes his last film, Gertrud

Another decade would pass before Dreyer got to make his next and final film, Gertrud (1964). Based on a play of the same name by Hjalmar Söderberg, the film is about a woman who makes absolute demands of men, asking for unconditional love. In the years between The Word and his last film, Dreyer had gained a degree of recognition he had never known before. Ebbe Neergaard’s book on Dreyer came out in 1940, an English edition was published in 1950 and a revised edition in 1963, published by the help of Neergaard’s widow, Beate Neergaard. Meanwhile, books about Dreyer came out in French, Italian and Spanish, and a steady stream of articles were appearing the world over. In 1959, Dreyer was named Honorary Artist by the Studenterforeningen students’ association, and the same year a collection of his articles on film was published as Om film (About Film). On his 75th birthday in 1964, the papers were full of tributes. The same year, four of his screenplays were published as Fire Film af Carl Th. Dreyer (Four Films by Carl Th. Dreyer).

Dreyer was planning Gertrud with Palladium in mind. The company had to adhere to a certain level of quality in order to keep its production license. Since Palladium had rented its own studios to the Danish Broadcasting Corporation, the studio shooting was done at Nordisk Film’s studios. Dreyer consequently ended his directing career in the exact same studio at Nordisk where he had first begun 46 years earlier. During the shoot, he presented the film as follows, "It is this strong and passionate woman’s tragedy that she demands the absolute – the man she loves can be hers only, or she must leave him. This demand for the absolute is her hubris, for which the gods punish her." (Politiken, 21 May 1964).

The film had its world premiere in Paris, where Dreyer had always enjoyed a special status. Though the young New Wave directors, in particular, hailed him as a master, the premiere was a scandal. The cinema was new and not actually ready to screen films. Mainly, however, the film’s whole visual and narrative style was simply too strange, and a handful of dedicated souls later felt compelled to systematically defend the film in a subsequent issue of Cahiers du Cinéma. Nor did this singular film get the reception it deserved in Denmark. Discussing the film’s reception in the film journal Kosmorama, No. 69, Ib Monty, director of the Danish Film Museum, sarcastically remarked, "It’s incredible that this could happen again. Carl Th. Dreyer’s new film, 'Gertrud,' had its world premiere in Paris. The Danish papers, almost to a one, had dispatched their big shots, the well-established, official typeballs, and they all, with one commendable exception, seized the opportunity to once again reveal their ineptitude and impotence in the face of that which they do not expect." One of these typeballs was Jens Kruuse of Jyllands-Posten, who began his article, "With petrified horror we watched image upon image on the small, crooked and wrinkly screen in the half-finished Paris cinema. Will not Carl Th. Dreyer’s genius, Hjalmar Söderberg’s refined, subtle truths or the grandiosity of the subject succeed in saving this film? we prayed silently but in vain."

Medea and Maria Callas

Dreyer, as usual, took the criticism and the subsequent debate in stride. He had made a film he could be proud of and he was thinking about the many projects he wanted to realise. One was Medea, for which he had nearly finished writing the script. According to Drouzy, he had almost signed his star, Maria Callas – who, ironically, would play the same part a few years later in Pasolini’s 1970 adaptation. Dreyer’s Medea was finally realised in 1987, 19 years after his death. Lars von Trier, who earlier had announced his inspiration from Dreyer, directed a TV version from Dreyer’s script. Dreyer intended Medea to lead into his life’s project, Jesus of Nazareth. Neither made it off the drawing board. From 1966 to his death in 1968, even while he was repeatedly hospitalised, he kept toying with projects. In March 1968, he came down with pneumonia and died, on 20 March, at age 79.

The Two Sides of Dreyer

The course of Dreyer’s life, it seems, can neatly be divided into two careers, or two personalities: one is the young daredevil, balloonist and reporter, risking his life to get the scoop as the first passenger on a cross-Sound flight. The other is the quiet burgher who spent the last 30 years of his life quietly living with his family in a modest apartment on Dalgas Boulevard in Frederiksberg. The early years are rife with stories of the young, self-assured hothead, playing the part of the great artist to his bosses at Nordisk Film, though ultimately losing the power games. Likewise, stories of the cocky young reporter abound. Peter Schepelern makes a good point in his book Tommen, on Dreyer’s film journalism, that "you might say it’s actually a redeeming feature of this otherwise so severe and profoundly serious artist that he started out as a silly, cheeky hack." The director he would become is characterised by Lars von Trier in a short piece in Kosmorama, No. 187, 1989, on the centenary of Dreyer’s birth, "Carl Th. Dreyer cultivated the bourgeois virtues. His home was decorated in a taste that was clean and unadorned in the middle-class fashion of the time; his appearance was reserved and polite, his entire existence was regular and punctual. […] Carl Th. Dreyer was a modest man, as were his sitting room and, later, his grave. Carl Th. Dreyer possessed the pure heart and natural humility of the passionate individual. Carl Th. Dreyer’s passion was FILM." At the same time, this quiet man was ready to pack up his belongings and leave for the US on a moment’s notice as soon as he got the green light from his American producer that he could start shooting his Jesus film. But word never came.

Dreyer may have been a good burgher in middle age, but his view of cinema and his own place in it bore the imprint of the young balloonist’s self-esteem and self-image. Steadfast he stood by what he had created, even when the press and the public were against him.

By Dan Nissen | 08. september