The obvious problem that confronts anyone writing about Dreyer’s use of music in film is that the majority of his narrative films were made in the silent era when control over music was in the hands of the exhibitors. Such was the case even for La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), a film over which Dreyer otherwise had complete artistic control. To compound the problem, of the four remaining features, all of them sound films – Vampyr (1931), Vredens Dag (Day of Wrath, 1943), Ordet (The Word, 1955) and Gertrud (1964) – Vampyr bears many hallmarks of silent film, not least in its virtually through-composed score. That leaves us with only three sound films to consider, and though music plays a major role in all of them, it does so in distinctively different ways.

Dreyer’s musical background was fairly typical for a member of the Danish bourgeoisie in the early years of the twentieth century. He received free piano lessons and even for a while contemplated becoming a professional musician, though that seems to have ended after only one engagement as a piano player in a bar.1 The various clippings about recordings, radio broadcasts and concerts found in his archives point to a continuing interest in music in his adult life, attending concerts and buying records.2

Frustratingly, he has little specific to say about the use of music in film. He talks frequently of rhythm in film – of camera and actors’ movements, of cutting – but his use of the term in relation to musical rhythm is imprecise and often used as a synonym for tempo. One comment, though, stands out, this from his essay ‘A little on film style’:

I cannot talk about film without saying a couple of words about music. It is Heinrich Heine who has said that where the words come out short there the music begins. This is just the task of the music. Correctly used, it is both capable of supporting the psychological development and of deepening a frame of mind that has been previously produced either through the pictures or through the dialogue. When the music really has meaning or an artistic intention, it will always be a plus for the film. But we must, nonetheless, hope for – and work to bring forth – more and more spoken films that have not the need of music, film in which the words do not come out short3.

Dreyer here describes a common expectation of film music, that it heightens – or underscores – the dramatic content of the film. It suggests that while music for Dreyer was a useful supplement, it was an element that he ultimately wanted to dispense with. And given the way that music is used in his last film, Gertrud, that seems plausible.

The silent films

As noted, Dreyer would have had little or no say in the music that accompanied his silent films. There is, though, a tantalising glimpse of his more earnest purpose for music in silent cinema: he approached the great Danish composer, Carl Nielsen, to write music for his film, Blade af Satans Bog (Leaves from Satan’s Book, 1921) only to be turned down on the grounds that it wasn’t art.4

Of all his films, La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc is the one that has received the most scores, particularly since the extraordinary discovery in 1981 of a pristine positive of the director’s original cut in the Dikemark Sygehus near Oslo.5 Since then, barely a year has gone by when musicians haven’t honoured Dreyer’s creation, in part precisely because of the lack of any clear prescriptive demand on his part, and because the film has proved itself receptive to so many different musical styles. In 1982, La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc received a commissioned score by the Danish composer Ole Schmidt. From the classical world, Richard Einhorn’s 1994 Voices of Light, described as an oratorio, is probably the best known (featured on the Criterion edition of the film). Scored for orchestra and chorus, it also gives a nod to modern performance practice of medieval music by using the American female ensemble Anonymous 4 to represent Jeanne. From the pop world come scores by Cat Power, Nick Cave and the Dirty Three, and more recently, a score by Adrian Utley of Portishead and Will Gregory of Goldfrapp (this can be found on the more recent Criterion re-release of the film). At the risk of charges of self-promotion, I also cite Voices Appeared, a score compiled of music from the lifetime of Joan of Arc which I designed and have performed with The Orlando Consort since 2015.6

La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc had two premieres, one in Copenhagen on 21 April 1928 and one in Paris some six months later on 25 October. For the former, Jakob Gade, the musical director of the Palads Teatret, created a composite score from extant music, the details of which have been lost. The Paris premiere, delayed because the French Catholic authorities demanded cuts, earned a commissioned score by Victor Alix and Léo Pouget. The piano reduction and some of the string parts have survived, and though it has been performed in the modern day, aligning its thirteen movements with the various intertitles and action cues indicated in the score is no easy task.7 Stylistically, the music aims for a broad correspondence with the action: a comic, farting bassoon apes the buffoonish English soldiers when they taunt Jeanne in her cell; and rising sequential passages ramp up the tension during the graphic scenes of Joan at the stake and the subsequent riot. In addition to the instrumental ensemble, various recitatives and choral sections comment on the action, the lyrics of which, written by Serge Plaute, underline Jeanne’s nationality and her saintliness (she had been canonised in 1920).

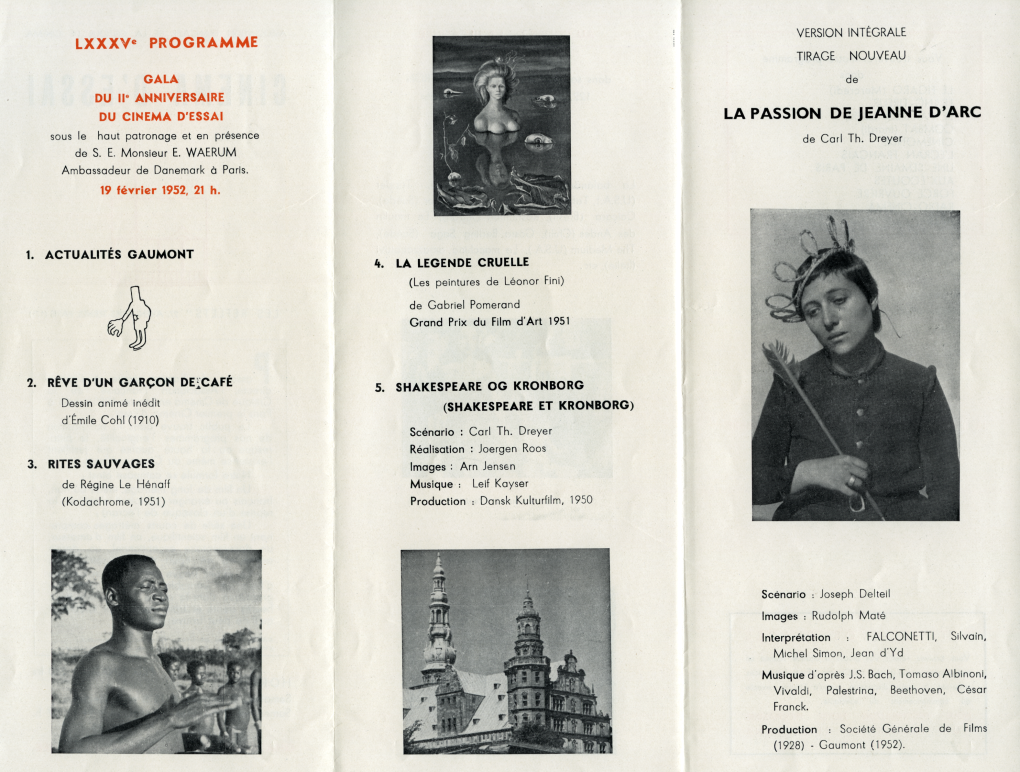

Dreyer claimed to know nothing about the score so there’s no way of telling what he made of it.8 The story of a later sonorised version, while more complicated, provides at least a sense of what Dreyer might have preferred. In 1952, an Italian film historian and co-founder of Cahiers du Cinéma, Joseph-Marie Lo Duca, discovered a print of the second ‘lost’ B negative in the Gaumont vaults and, to great fanfare, was first screened at the Cinéma d’Essai in Paris on 19 February 1952. It enjoyed an extended run through March and the soundtrack patrons heard was a confection of Beethoven, Bach, Cesar Franck, Palestrina, Albinoni and others, played back over a wire recorder.9

Dreyer was withering in his condemnation, saying that he knew it wouldn’t work, the rhythm of the music being quite different to that of the film.

I knew that my rhythm would be destroyed, it is not the rhythm of the music of a Bach or a Beethoven; what concerned me was that the actual texts of the trial did not function as a rhythmic pause, because in silent film titles were embedded organically, like pilasters in a building.11

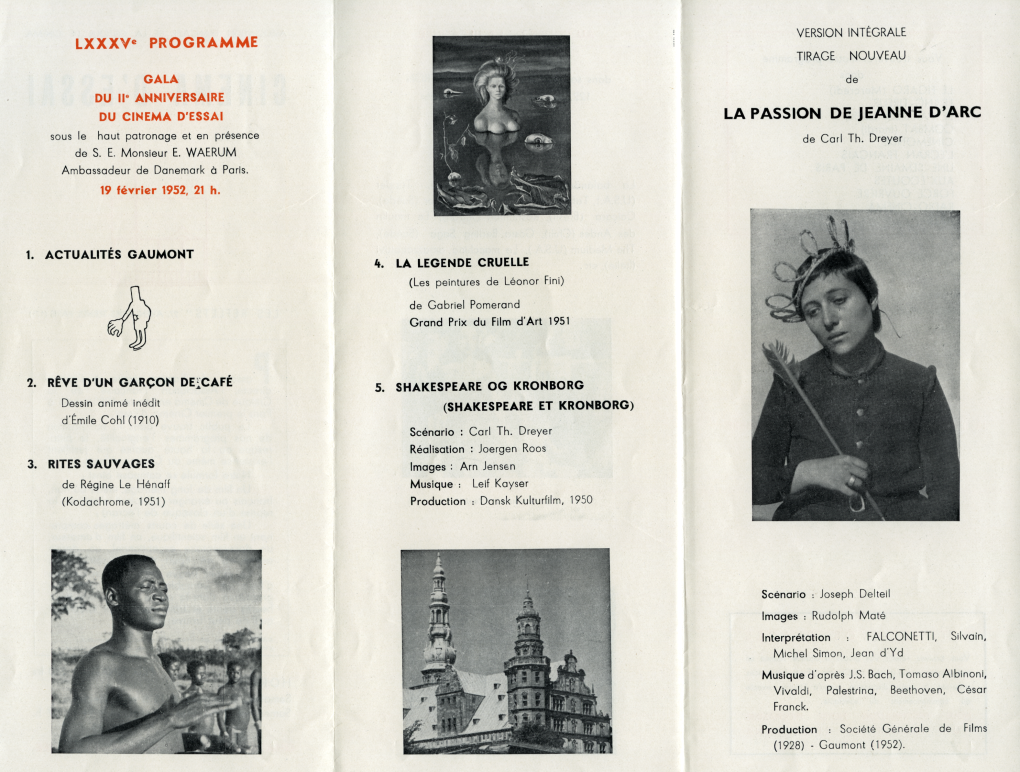

That may have been true, though Dreyer was being disingenuous: he never attended any of the screenings in Paris. The version he saw, though not until 1956, was the sonorised print in circulation until 1988, created in the first instance for a screening at the Venice Biennale on 12 September 1952, the music of which was exclusively Baroque.12 Most of this was taken from two LPs of music performed by L’Ensemble Instrumental “Sinfonia”, leader Philippe Lamacque, directed by Jean Witold for the Éditions Phonographiques Parisiennes label, SLP1 and SLP2, part of a series that championed the music of Albinoni in particular.13

Lo Duca’s choices were thus not the result of careful and eclectic selection that drew on a specialised knowledge of Baroque repertoire but prompted in the first instance by expediency; he had presumably obtained permission to use the recordings through some kind of lease arrangement. He was also perhaps encouraged by the popularity of Albinoni’s Adagio in G minor. At the time, the Adagio was known to French audiences as the theme tune for a Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française weekly programme called ‘Sinfonia Sacra’, presented by Jean Witold and Carl De Nys.14 However, it was not composed by Albinoni but by the Italian musicologist and biographer of Albinoni, Remo Giazotto, sometime in the late 1940s. Lo Duca was the first to use it as film music, since when it has become a perennial favourite in movies such as Rollerball (Norman Jewison, US, 1975), Gallipoli (Peter Weir, AUS, 1981) and, most recently, Manchester by the Sea (Kenneth Lonergan, US, 2016). To supplement the music from discs, Lo Duca arranged a new recording of Alessandro Scarlatti’s St John Passion, most of which would be used in the final crowd scenes.

When he finally saw Lo Duca’s creation, Dreyer condemned the score for anachronism, a criticism consistent with his research-led approach to his film projects in general and to La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc in particular.15 This was slightly unfair in that he had earlier professed himself happy with the idea of adding Bach’s music. His various negative comments about Lo Duca’s film have led to the idea that he wanted the film to be viewed in silence.17 Writing in 1973, the film scholar David Bordwell noted that ‘La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc is one silent film that doesn’t suffer by being shown without music’, and advised readers to rent either the MoMA print or the Lo Duca version and switch the sound off the latter.18 And indeed it is in this way that Nana, the heroine of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1962 Vivre Sa Vie, watches the Lo Duca print in that movie.

There is some justification for that approach, though I believe Dreyer’s own view has been exaggerated. Directors of silent film often used music on the set to prompt the appropriate emotional response in actors and a 1927 article by the critic Jean Arroy reported that Dreyer eschewed this practice as an artificial device, contrary to his search for emotional truth. Dreyer, however, went further: he was ‘a believer in film projected without musical accompaniment’.19 The context of the interview in a special issue of Cinémagazine, though, render his comments less doctrinal, as the preference of one who, at the time, was constructing his movie in silence in an editing suite. Furthermore, in the extensive correspondence with Lo Duca, where he on more than one occasion expressed reservations about the direction in which the Italian was taking his restoration, nowhere does Dreyer express any hesitation about the plans to add music.

Vampyr

Perhaps the strongest case for Dreyer preferring music with his silent films is, paradoxically, the first of his sound films. While technically Vampyr is his first venture into sound, the minimal dialogue and use of intertitles betray a silent-film aesthetic.20 That is also apparent in Wolfgang Zeller’s extensive musical score, which strongly suggests that Dreyer had an expectation of the almost-constant presence of music in silent film.

Zeller had trained as a violinist and was the in-house composer for the Volksbühne theatre in Berlin from 1921 to 1929 and was known at the time for his score for the first full-length German sound film, Walter Ruttmann’s Melodie der Welt (1929). His handwritten score for Vampyr, held in the Deutsches Filminstitut in Frankfurt, is arranged for strings (violins, violas, cello, double basses), woodwind (clarinet, bass clarinet, bassoon, alto saxophone), percussion (piano, celesta, cymbal, timpani, bass drum, quijada) and brass (trumpets, trombones, tuba).21 It runs to some 200 pages and consists of 61 cues. The musical material displays a convincing organicism: discrete musical cells – awkward intervals, distinctive rhythms, orchestral colours – are developed into themes that are associated with specific characters, this a fairly standard approach to film music that draws on the Wagnerian idea of the leitmotif. Some cues are very short – cue 7, for example, is merely a direction to supply the sounds of a church bell and a knock on the door, and cue 50 similarly specifies tam-tam and cymbals, this to produce an eerie sound – while other cues run to several pages. Sync moments of various kinds are scribbled into the score: characters (‘David’, ‘Gisele’), locations (‘schloss’,) dialogue (Gray’s ‘Wer sind Sie’ to the Chatelain), identifying features (‘trappe’ for staircase), or intertitles (‘karte’). The music was recorded in a studio while the film played. Some cues are missing and some were improvised. The manuscript for cue 4, for example, lacks any indication of the throbbing pedal point that accompanies the shot of the unidentified man with a sickle. Other more basic effects, including animal sounds, were created by vocal impressionists in the studio.22

According to Martin Koerber, who worked on the restoration of the film, the film’s editor, Paul Falkenberg, was required to post-synch the film in the three languages of its release, English, German and French. The second optical soundtrack was reserved for the music and other effectssuch as thunder, a rifle shot, bells, and other basic Foley sounds, some of which are notated in Zeller’s score, and which were cued by the conductor. A primitive editing machine combined the two optical tracks to marry dialogue and music.23 However, this led to a distinct loss of quality, a consequence of which was the use of more basic musical material when dialogue is spoken. Pedal points and paused chords are Zeller's imaginative solutions, a subtle and simple form of underscoring that embraces the technical limitations of the early sound era whilst at the same time heightening the generally ominous mood of the film.

As well as augmenting the film’s emotional design, the music also dramatizes a central theme of the film, that of good versus evil. The former is represented by a consonant Mozartian idiom while the latter invites the score’s more dissonant harmonies. When Allan Gray ponders a picture in his room of a deathbed scene overseen by a priest, a hymn-like cue promises Christian redemption. Elsewhere, a solemn lament accompanies the Chatelain’s paternal vigil, and a funereal dirge played on low brass gloomily portends Gray’s potential fate. Against this are more angular cues – one for the evil Doctor, an eerie theme on the alto sax for the infected Léone – many of which foreground the musical interval of the augmented fourth, or diabolus in musica as it is often termed, a common horror trope. Zeller, though, never tests the listener’s patience with repetition, and remains inventive to the end.

There is also a telling use of silence, particularly notable given music’s otherwise persistent presence. When Gray is seemingly buried alive in a coffin there is no crashing orchestra to remind us that we should be scared, only the cruel rasp of screws biting into wood. Similarly, when the vampire is slain we have no blasting brass or percussion, only the stark tolling of bells and the sound of a metal stake being driven into the monster’s body. Dreyer clearly valued music, but he was no less aware of the potential horror of its absence.

Vredens Dag, Ordet and Gertrud

Twelve years passed before Dreyer made his next sound film, Vredens Dag, and his return to feature-film making was paved by directing the documentary short Mødrehjælpen (Good Mothers, 1942) for which Poul Schierbeck (1888-1949) wrote the music. This was the start of an enduring partnership and it is no exaggeration to say that he was Dreyer’s first-choice composer. Schierbeck is probably best known today as the composer of the music for Denmark’s unofficial national anthem, ‘I Danmark er jeg født’ (‘I was born in Denmark’), but he was an organist of note and a significant composer of the post-Nielsen generation, with several large-scale symphonic works to his name as well as an opera and many songs. The brief cues for Mødrehjælpen, like that for the later Vandet paa landet (Water from the Land, 1946) show a fondness for folk-like modal melodies, and the lush string writing evokes bleak Northern landscapes.

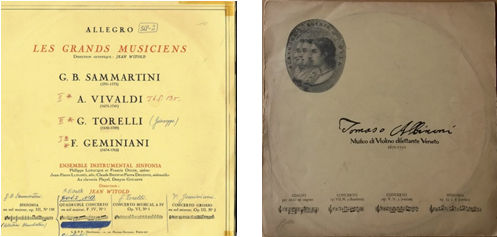

In many ways, the use of music in Vredens Dag is the most conventional of Dreyer’s oeuvre: as an aural shock, signalling the mental state of characters, and amplifying dramatic situations. And like Vampyr, music dramatizes the film’s central moral debate. ‘For the Overture the desired effect is as if it were Doomsday’, Dreyer instructs in a personal typed note to the projectionist of the premiere, ‘and it is essential for the levels to be at full volume, that is as loud as the sound system can take, and right from the start of the film’.24 The sonic assault is heightened by an initial silence that holds over an opening shot of the title in illuminated gothic script. Suddenly the main theme blasts out, played by trumpets, trombones, tam-tam and portentous, low-pitched, juddering strings. The cue is an arrangement of the Dies irae, a thirteenth-century sequence familiar to twentieth-century audiences through its frequent quotation by classical composers from Mozart to Rachmaninov, and in film scores from Gottfried Huppertz’s score for Metropolis (Fritz Lang, GER, 1927) to The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, UK/US, 1980). The scrolling images it accompanies show a vengeful Christ in the heavens, arm raised, his foot on the world, ready to enact judgement on those who transgress:

The use of Gothic script in the opening shot implies that the poem to which the tune is sung is an authentic historical document though it was actually written by Paul La Cour (1902–1956), who had acted as assistant director on La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

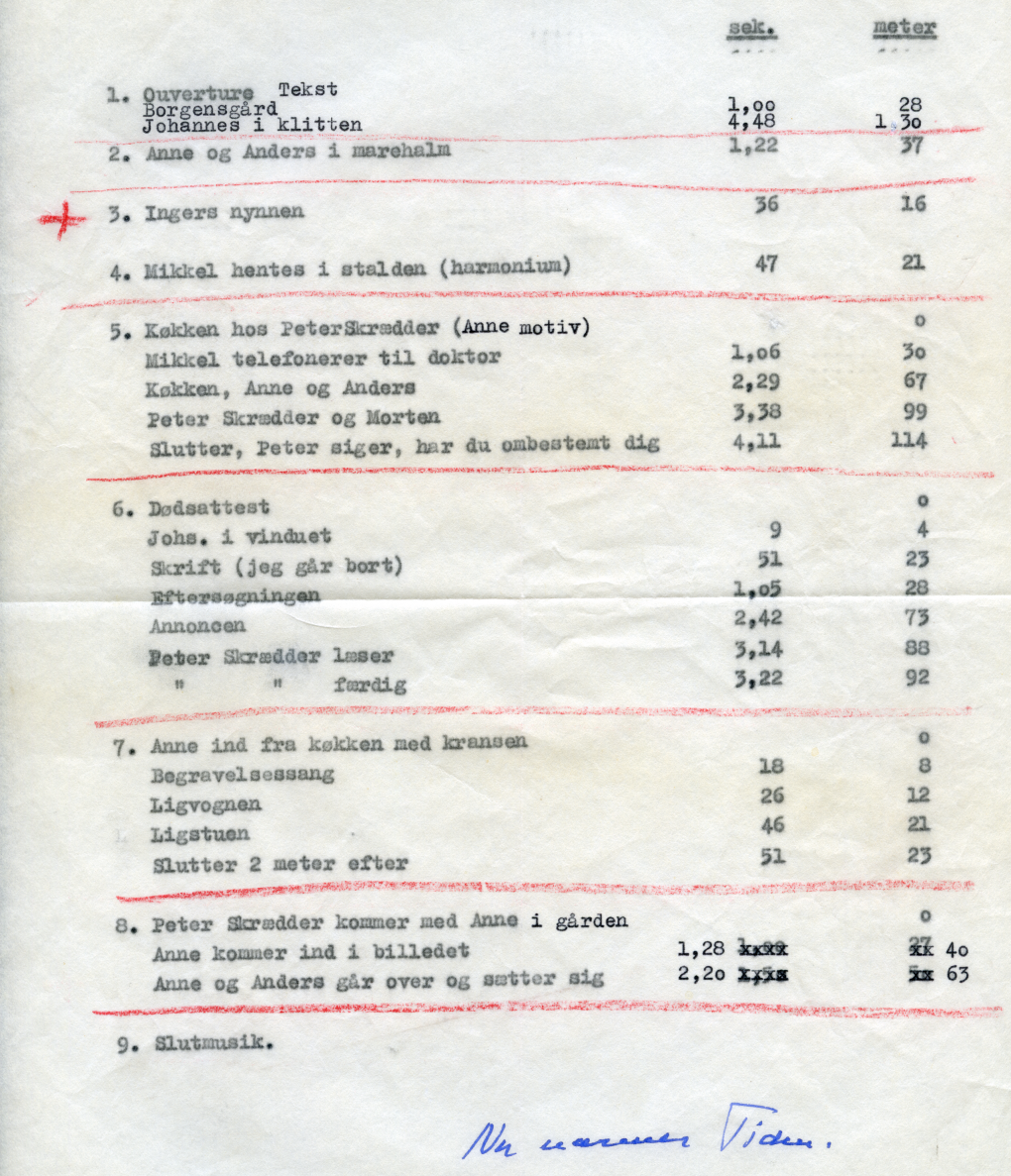

Dreyer’s personal typewritten draft of the music cues for Vredens Dag.25

The second cue, notated by Schierbeck as ‘Annes angst’ (Anne’s consternation), shows Dreyer using music to illustrate the psychology of a character. Anne emerges through a door, glances behind her, and advances through the church:

We are ignorant of her destination and the reason for her worry, and little of the mise-en-scène suggests that Anne is afraid. Indeed, the elegantly smooth track-and-pan contradicts her hurried walk, which even at moments seems relaxed. It falls on the music to instruct the spectator. Marked Molto allegro and Molto allegro inquieto, the cue begins over a dissolve with an agitated string motif like a sharp intake of breath, punctuated by stabbing muted trumpets playing in thirds. This opening motif, hesitant and interrogative, repeats in a loose sequence, ending in a scurrying descent into silence, coinciding with Anne’s momentary disappearance behind a column. She emerges back into view as a rising, urgent cello phrase invites a repeat of the opening violin phrase that leads to a diminished 7th chord in the brass, which crescendos and ushers in anxious dotted rhythms and semiquaver runs over tremolo strings.

Of all the cues in the film, arguably even of Dreyer’s oeuvre, this is the most conventional, though rivalled for affective association by the longest cue (cue 5 in Dreyer’s typewritten notes, though actually cue 7) subsequently published as Pastorale.26 There is no forbidding brass here, only rich strings, the occasional tink of a triangle and a solo violin, painting an idealised expression of romantic love when Anne and Martin escape the confining rectory. Such innocent musical celebration is the musical antithesis of the opening assertion of repressive and judgemental religion, and the Dies irae returns in the final scene to haunt the young Anne, accused, like Jeanne, of witchcraft. This recapitulation is the conclusion of a musical argument staged earlier in cue 4 and clearly echoes Dreyer’s sketched description: ‘Torture chamber, The Forest, Dungeon’.27 The Dies irae theme is quoted gently and liltingly at the beginning and soon gives way to a more expansive variation led by a solo violin, the instrument most commonly associated with love. But the lovers’ freedom is soon cut short when they spy a horse and cart carrying wood for Herlofs Marte’s execution, at which point the Dies irae returns threateningly in the lower strings to remind them of the social order which opposes them.

Dreyer subsequently worked with some of Denmark’s other famous composers on various shorts: Thorvaldsen (1949) and Storstrømsbroen (The Storstrøm Bridge, 1950), contemplative film essays on the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen and the Storstrøm bridge, each feature dramatic tone poems by Svend Erik Tarp and Svend S. Schultz respectively. But it was to Schierbeck that Dreyer turned for his score for Ordet. Schierbeck, though, had died in 1949 and it was his widow, Sylvia, whom Dreyer consulted. Together with Emil Reesen, they compiled short excerpts from Schierbeck’s work to create a score that convincingly serves Dreyer’s intimate portrait of life in Jutland at the turn of the century.28

The opening cue seamlessly stitches together a short section from Natten (The Night op.41), a rare calm tonal moment from a twelve-minute programmatic piece that presents a very nightmarish version of night-time, with music from Andante Doloroso (op.57 no.2). The latter’s rising-and-falling sequential phrases conjure images of the ebbing sea that lies over the dunes upon which Johannes wanders. Later cues, such as the mournful section from Radio-rapsodi (op.49) heard when the Peterson family arrive at Borgensgård for the funeral, beautifully establishes a mood of sad solemnity. Like Vredens Dag, music in Ordet plays an important role as an illustration of communal life. And, as one might expect given Dreyer’s almost obsessive eye and ear for detail, each instance is carefully researched. Schierbeck, a church organist all of his working life, had written several hymns which were perfectly suited to the task and Sylvia deserves recognition for coaxing from the Jutlanders a spirited rendition of ‘Lyksalig, lyksalig hver Sjæl, som har Fred!’ (‘Blessed, blessed [is] every soul that has freedom’), achieved only with the judicious medication of schnapps.

Strikingly, given the otherwise emotive use of music, Dreyer does not use music at all in the climax of the film, a scene in which it is easy to imagine and indeed anticipate its presence.29 Nor, judging by Dreyer’s original cue sheet, did Dreyer even consider it a possibility:

The denouement thus unfolds in almost complete silence, a state that has defined Borgensgård since Inger’s death. Though Ordet is a melodrama, Dreyer seems to be moving towards a system wherein the two elements, melos and drama, are kept at a distance. Only when the final word of the film, ‘Life’, has been uttered, does music encroach, playing as the film fades to black and thereafter for almost a minute, a notably extended sequence in any context, the more so as there are no final credits.

For Dreyer’s final film, it was never going to be possible to assemble a score from Schierbeck’s music. The music required for Gertrud was very specific: something written in the forward-thinking idiom of the early twentieth century, this in the shape of compositions by the young fictional composer, Erland Jannson, the lover of the retired soprano, Gertrud. The task fell to Jørgen Jersild (1913-2004), an extension of filial trust in so far as he was a pupil of the late Schierbeck.31 The main composition was ‘Sang i natten’ (Song in the night), with lyrics written specially for the film by the Danish poet, Grethe Risberg Thomsen. The collaboration between poet and composer also produced five vignettes – poems with music, designed to punctuate the film’s various acts – which were ultimately cut from the film.32 Dreyer, though, retained some of the music, which is linked orchestrally and thematically to the character of Jannson. Jensen also helped Dreyer with reshaping Heine’s lyrics of ‘Ich grolle nicht’, the song from Robert Schumann’s song-cycle, Dichterliebe, that Gertrud, once more accompanied by Jannson, performs and which causes her to break down on the telling line ‘Ewig verlor’nes lieb’ (forever-lost lover).33 Jersild’s song provides much of the musical material in the film, including a piano arrangement that is heard over the opening credits and in the background of the celebration held in honour of Gabriel Lidman, arranged for string trio. ‘Sang i natten’ is also linked with the Schumann song, echoing the opening phrase and the angular arpeggiation of the first song of Dichterliebe, ‘Im wunderschönen monat mai’.

The main purpose of the music in Gertrud, then, is as a vehicle for text and for symbolic resonance. Nearly all the music is diegetic, which is to say music whose source is within the fictional world. Only at the end of the film, as an older and wiser Gertrud bids farewell to her old friend, Axel Nygren, does the music come from the nondiegetic realm, music whose source cannot be witnessed by the fictional characters. It provides a wistful and more tonal closure, reassuring us that Gertrud harbours no regrets for the choices she has made in her life.

Gertrud is thus a film about music rather than a film that exploits music. In many ways this parallels Dreyer’s own filmic journey, wherein shot lengths increase together with tracking-and-panning. Dramatic expression is increasingly contained, so that by the time we get to Gertrud, actors deliver their lines almost flatly. Music traces the same path, becoming increasingly part of the action rather than being yoked to narration.

The seeds of Dreyer’s refusal of music’s coercive potential were sewn early – in Vampyr’s stunning use of silence and Ordet’s similarly restrained final scene. The eschewal of music at such dramatic climaxes amounts almost to a distrust of music’s undeniable potency that is also found in some of the shorts. De nåede færgen (They caught the ferry, 1948), for example, a suspenseful interpretation of Johannes V. Jensen’s short story from 1925 has only a doom-laden drum over the opening and closing credit sequences, sound otherwise limited to dialogue and the unsettling whine of the motorcycle engine. Dreyer, it seems, is convinced that such scenes speak for themselves, that his cinema is one wherein ‘words do not come out short’.

My thanks to all the staff at the Carl Theodor Dreyer Collection (DFI) for their help over the past three years, without which this essay would be the poorer. Particular thanks are due to Lisbeth Richter Larsen for her valuable comments and sharp editorial eye. Thanks also to Angus Chisholm and Lone Skov for their help with translations.

Notes

1. Jean Drum, and Dale D. Drum, My only great passion: the life and films of Carl Th. Dreyer (Lanham: Scarecrow Press, Inc, 2000) 21.

2. James Schamus, ‘Dreyer’s Textual Realism’ in Carl Th. Dreyer (New York: MoMA, 1988), 61.

3. Carl Theodor Dreyer, ‘A little on film style’ in Donald Skoller, ed. Dreyer in Double Reflection (New York: Da Capo, 1973), 141. It is significant that both Peter Schepelern and I should begin our respective essays on Dreyer's use of film with this quote. See 'Når ordet kommer til kort – Carl Th. Dreyer og musikken' on this website: https://www.carlthdreyer.dk/carlthdreyer/om-dreyer/filmisk-stil/nar-ordet-kommer-til-kort-carl-th-dreyer-og-musikken.

4. ‘Jeg tror det var Carl Nielsen, der afslog at ville lave musik til en film som jeg skulle lave fordi han sagde, filmen var ikke kunst.’ 'I think it was Carl Nielsen who turned down writing the music for a film I was making because he said that the film wasn’t "art".’ (my translation) https://www.carlthdreyer.dk/carlthdreyer/galleri/film-filmklip-interview. My thanks to Angus Chisholm for help with the transcription.

5. On the convoluted history of the various prints of the film, see ‘The Different Versions of "Jeanne d'Arc"’ by Lisbeth Richter Larsen on this website: http://english.carlthdreyer.dk/Films/La-Passion-de-Jeanne-dArc/Articles/De-forskellige-versioner.aspx.

6. See http://www.orlandoconsort.com/voicesappeared.htm. For further examples, see Peter Schepelern, op.cit. on this website: https://www.carlthdreyer.dk/carlthdreyer/om-dreyer/filmisk-stil/nar-ordet-kommer-til-kort-carl-th-dreyer-og-musikken.

7. Gillian B. Anderson has performed the original score and described some of this difficulty. See Gillian B. Anderson, ‘The Shock of the Old: The Restoration, Reconstruction, or Creation of "Mute" Film Accompaniments’ in The Routledge Companion to Screen Music and Sound ed. Miguel Mera, Ronald Sadoff and Ben Winters (New York: Routledge, 2017), 201-212. Six recordings of cues from the score, originally issued on Columbia (D 19253, D 19254 and D 19256) can be heard on an online encyclopaedia of music used in French theatre and radio between 1918 and 1944: http://194.254.96.55/cm/?for=docum&cledocum=alix_jeannedarc. The four indications in the score of physical acts – ‘the soldier picks up the crown with his sword’, ‘he puts the crown on Jeanne’s head’, ‘the arrow’ and the intertitle ‘She really looks like a daughter of God, eh?’ – do not align at all if we follow the tempo marking of crotchet=88. Indeed, at that speed the cue lasts only two minutes while the cue itself is marked c.3 minutes. The recording of that cue, though, which involves complex repetitions, fits the scene perfectly and matches its emotional contours.

8. A brief exchange with a Monsieur G. Carré of the Ciné-Club de Chartres, who was seeking information about the music used for the premiere of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, elicits a perfectly polite expression of ignorance on Dreyer’s part: he knows nothing about the music used. See DA: DII, A, 299 and 300.

9. For a different perspective, see Casper Tybjerg, ‘Cinephiliac and Political Passions: Seeing Dreyer’s Jeanne d’Arc at the Cinéma d’Essai’ in Nordic Film Cultures: A Globalized History of Cinematic Elsewheres, ed. Arne Lunde & Anna Stenport (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, forthcoming). For more on the Lo Duca sonorised version, see Donald Greig, ‘Lo Duca and Dreyer: Baroque music, extant recordings and aleatoric synchrony’, Music and the Moving Image, 13 (2) (2020), 25-61.

10. DA: DI, A, Jeanne d'Arc, 2.

11. 'Je savais que mon rythme serait détruit, ce n'est pas le rhythm de la musique d'un Bach ou d'un Beethoven; cela m'effraie que le texte veritable du procès ne serve plus de pause rythmique car dans le film muet, les titres étaient encastrés organiquement, tels des pilastres dans un bâtiment.' Lotte Eisner, ‘Rencontre avec Carl Th. Dreyer’, Cahiers du Cinéma no.48 (June 1955), 2.

12. “Gaumont Will Withdraw Its Sound Version of Dreyer’s "Joan of Arc”’, Variety, June 28, 1989.

13. Source: WorldCat. The OCLC Number of the recording is 53235794

14. A generally favourable review by Jean Germain makes reference to the signature theme. See Disques, nouvelle série, vol.V No 50, 30 September 1952, 457.

15. As well as going back to the original court records, this with the help of Pierre Champion, a French historian who acted as historical consultant, the set designs clearly also derived from fifteenth-century drawings. See Britta Martensen-Larsen, ‘Inspirationen fra middelalderens miniaturer’, Kosmorama 39, no. 204, (1993), 26-31.

16. Letter from Dreyer to Lo Duca 4 February 1949: ' I think it an excellent idea to choose J.S. Bach for a musical accompaniment provided that you do not introduce any other sounds’. DA: DII,A: 1649

17. A qualified version of this appears in the accompanying booklet to the Eureka Entertainment edition: ‘As far as is known, Dreyer’s preference was for La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc to be shown in silence, with no musical accompaniment.’ The Passion of Joan of Arc, directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer, Eureka Entertainment Blu-Ray EKA70267 booklet, 2.

18. David Bordwell, Filmguide to La passion de Jeanne d'Arc (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1973), 79.

19. Jean Arroy, ‘Carl Dreyer’ in Cinémagazine (Special edition, 1927), 29-39. This edition falls somewhere between a magazine and trade promotion, with pictures of its stars and extensive space devoted to information on how to order the film.’

20. Noël Carroll refers to Vampyr as one of a series of ‘silent sound films’ made during the transition to sound between approximately 1928 and 1931. See Noël Carroll, ‘Lang, Pabst, and Sound’ in Ciné-Tracts 2 no.1 (Fall, 1978),15–23.

21. WZ 39 Nachlass Wolfgang Zeller/Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt am Main.

22. According to Martin Koerber, the voice shouting ‘Ruhe!’ was cued by Zeller from his score. However, there is no such indication there, only an instruction: ‘Plötzlicher abbruch’ (abrupt stop). Martin Koerber, ‘Some notes on the restoration of Vampyr’, in: Vampyr, directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer, Eureka Entertainment DVD, EKA40215 booklet, 59. An earlier version of the article appeared in Danish in Film 7, (Feb., 2000).

23. I am grateful to Martin Koerber for clarification on this issue. Private correspondence of 23 March 2018.

24. ‘For at Ouverturen kan faa den tilsigtede Dommedagekarakter, er det vigitict, at den gengive med fuld Styrke d.v.s. med saa stor Styrke som Tonsanlæget overhovedet kan taale, og det straks fra Filmens Start.’ (original emphasis). DA: I, A: Vredens Dag, 57

25. DA: DI, A: Vredens Dag, 56. Schierbeck's score is part of the Poul Schierbeck collection held in the Danish Royal Library, Copenhagen.

26. The published copy held in the Dreyer archive was sent to Dreyer by Poul Schierbeck on 12 November 1943 and personally inscribed: ‘To Carl Th Dreyer. In grateful reminder of unforgettable cooperation. From your very devoted Poul Schierbeck’ (‘Til Carl th. Dreyer. i taknemmeligt minde om uforglemmeligt samarbejde. Fra Deres meget hengivne Poul Schierbeck’) DA: DI, A: Vredens Dag, 4.

27. ‘Torturkammer, Skoven, Fangekælder’ DA: DI, A: Vredens Dag, 57.

28. For this and following, see Oddvin Mathisen. Bogen om Schierbeck (Copenhagen: Nyt Nordisk Forlag Arnold Busck, 1988), 340-2.

29. I am being deliberately vague here so as not to spoil the ending for those who haven’t seen the film.

30. DA: I, A: Ordet, 78.

31. Jersild’s score and sketches are part of Jørgen Jersild's archive in the Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen.

32. A letter of 12 August 1964 from Thomsen to Dreyer indicates that she had sent texts to Jersild so he could assess the length and mood of each and get to work on them ‘as quickly as possible.’ DA: DI A: Gertrud, 13.

33. There are three separate sketches in his own hand, none of which Dreyer is happy with. DA: DI A, 13.

26. October 2018 | Donald Greig