To simplify Danish film history perhaps a bit unfairly, one could claim that only two directors really matter – Carl Th. Dreyer and Lars von Trier. The two gentlemen are groundbreaking innovators, supreme auteurs, towering over a landscape of jovial folk comedy and genteel mainstream realism. Dreyer and von Trier, makers of dark cinematic art, are kindred spirits with a strong artistic connection. Von Trier has, of course, been awarded the Carl Th. Dreyer Prize – in 1995, the 100th anniversary of cinema.

Moreover, Dreyer and von Trier have in common an almost eccentric detachment from the rumblings of the local echo chamber. It should be noted, however, that there is no counterpart to von Trier’s Dogme movement in Dreyer: no school ever formed around Dreyer.

Being Someone Else

Even their personal life stories have certain parallels that may or may not have shaped their artistic profile. As first revealed in Martin Drouzy’s 1982 biography, Carl Th. Dreyer født Nilsson (French edition: Carl Th. Dreyer né Nilsson, as Maurice Drouzy), Dreyer by all indications was the product of an illicit union between a Swedish maid, Josefina Nilsson, and a Danish landholder, Jens Christian Torp, at his farm Carlsro in Grantinge, southern Sweden. Born in secret in Copenhagen, he grew up the adopted son of a Danish couple, the Dreyers.

As a young man, he got in touch with his biological Swedish family, and it was apparently from them that he learned about his mother’s tragic end: pregnant again by another man who did not intend to marry her, either, she died after trying to provoke an abortion by taking poison. In his book, Drouzy argues that Dreyer’s entire production, focusing on the martyrdom of woman in a man’s world, can be viewed as a kind of monument to his mother.

Von Trier was the product of an extramarital union between his mother, Inger Høst, and her former boss at the Ministry of Social Affairs, Frits Michael Hartmann (1909-2000). Von Trier only found out about it from his mother when she lay dying in 1989. He looked up Mr Hartmann, who did not wish to have any further contact with his biological son. When he learned about the circumstances of his birth, Von Trier was working on Europa (1991), a film about Germany in the first few months after the nation’s collapse in 1945. A scene in the film can be viewed as a comment on his new-found knowledge. Von Trier plays a small role as a Jew who has been hired by the Americans to clear the president of a large railway company, Zentropa, by naming him as his saviour, thus enabling him to carry on as head of the company. The Jew shows up at the office of the railway boss, Hartmann (!), and declares, in front of witnesses, "Max Hartmann ist mein Freund; er hat mir Essen gegeben und mich in seinem Keller versteckt" (Max Hartmann is my friend; he gave me food and kept me hidden in his basement). Then, with a studied gesture, he embraces Hartmann, who is clearly uncomfortable at the pretence of familiarity and fake gratitude from a "friend" he doesn’t even know and never did anything to help.

The similar biographical backgrounds of Dreyer and von Trier can be seen as a factor creating a mood of isolation and alienation regarding a person’s self-image. Both had the experience of being someone else than who they thought they were.

Phobias, Anxiety and Dark Moments

Dreyer was a bit of a daredevil in his early years. As a young reporter, he obtained a balloonist’s licence. Von Trier, who suffers from a well-reported fear of flying, actually practiced hang-gliding in the western suburbs of Copenhagen when he was 19 (before crashing and injuring himself).

The phobias and experiences of anxiety that haunt von Trier have a certain parallel in Dreyer, who also had his dark moments, notably after completing Vampire (1932) when he spent several months in a French mental hospital. But while von Trier has always been extremely forthcoming about his traumas, Dreyer was extremely secretive, a quality that seems to extend to his art. Von Trier once characterised Dreyer thus,

"As a person, I believe, he was unbelievably boring. He was an office clerk. But I would say that, as opposed to Bergman, who has always, so to speak, opened himself up and talked about himself and maybe dared to make the most of that openness, Dreyer is more of a mystic" (Björkman & Nyman in Lumholdt, 2003, p. 101).

In the Torture Chamber

Ever since the beginning of von Trier’s career, he held up Dreyer as his idol of admiration, which coloured some of his earliest productions. Through his maternal uncle, the documentary filmmaker Børge Høst, young von Trier got a job at the erstwhile Statens Filmcentral, which afforded him the opportunity to view Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc countless times on the editing table.

The inspiration from Dreyer is quite apparent in von Trier’s first ambitious productions, Orchidégartneren (1978) and Menthe – la bienheureuse (1979), two half-hour films made on an amateur basis while he was in the Film Studies programme at Copenhagen University in 1976-79. Freely inspired by the erotic novel Story of O, the Menthe film includes torture scenes with chains shot in a whitewashed room that are very close to the torture scenes in Jeanne d'Arc.

Framegrabs from Menthe - la bienheureuse (Lars von Trier, 1970).

Also, there is a shot of Menthe standing by the window, shot from outside, that corresponds to a well-known shot in Day of Wrath of Anne by a window witnessing the witch burning.

Anne in Day of Wrath (Dreyer, 1943) and Mente in Menthe - la bienheureuse.

Medea – Directed by von Trier from a Dreyer Script

On the strength of these early films, von Trier was admitted to the National Film School of Denmark in 1979. There – helped by the director of photography Tom Elling and the editor Tómas Gislason – he developed his singular style, which first breaks through in his student film Nocturne (1980). He followed his graduation film Befrielsesbilleder (1982) with the features The Element of Crime (1984) and Epidemic (1987), the first two parts of his so-called Europa trilogy. In these films, it is probably easier to identify the influence from Bertolucci, Fassbinder and especially Tarkovsky, the Russian filmmaker who has remained a huge stylistic inspiration for von Trier’s work. Here, the Dreyer’esque element probably lies more in von Trier’s defining himself as an internationally oriented artist rising above provincial, commonplace Denmark.

Von Trier directly expressed his interest in and respect for Dreyer in the TV film Medea (1988), which he directed from an unrealised script by Dreyer. This is the only time von Trier ever worked with a script he didn’t write (or co-write) and his only adaptation of a literary source (Euripides’s Greek tragedy). Von Trier has explained how the film came to be made,

"I accepted the project because someone else would have taken it if I hadn’t. And it would have been horrible for me if someone else had taken it – to have to see someone else doing it. So I did it. But I would say that I’m not really directly inspired by Dreyer so much as I’m inspired by his way of directing. For I think that he’s a very honest director. He never made anything in a calculated fashion. Or, in other words, he always, so to speak, went against what was in vogue" (Björkman & Nyman, in Lumholdt, 2003, p. 101).

Still from Medea (Lars von Trier, 1988), produced by Danmarks Radio.

Medea had the look of avant-garde art, with a unique visual style achieved by transferring from video to film and back to video, and the film got a very negative reception, though it still stands as an innovative and daring experiment that also won a French TV award.

Reverence at Graveside

The following year, 1989, Dreyer would have celebrated his 100th birthday. The Kosmorama film journal celebrated the master in a series of articles, including a brief essay by von Trier, which concludes,

"Carl Th. Dreyer was a modest man, as were his sitting room and, later, his grave. Carl Th. Dreyer possessed the pure heart and natural humility of the passionate individual. Carl Th. Dreyer’s passion was FILM."

Newly founded TV2 also celebrated Dreyer’s centennial by broadcasting Gertrud. Introducing the film, von Trier, who purportedly had been in telepathic contact with Dreyer during the production of Medea, talked with programme director Peter Wolsgaard at Frederiksberg Cemetery. Pacing, von Trier praises his idol,

"Perhaps we can make a small experiment now, as we stand here at his graveside, and try to bring Carl Th. Dreyer’s spirit back to life by the faith of our childhood, as happens in The Word. I believe, if we all make an effort, we can lift the love of film that I see in very few places today, lift it up, so we can all benefit from it again." Upon which he reverently kneels at Dreyer’s grave and makes the sign of the cross.

Von Trier later appeared in a TV documentary about Dreyer that was part of the series Store danskere ("Great Danes") (Birgitte Lorenzen, DR, 2006).

Wearing Dreyer’s Tuxedo

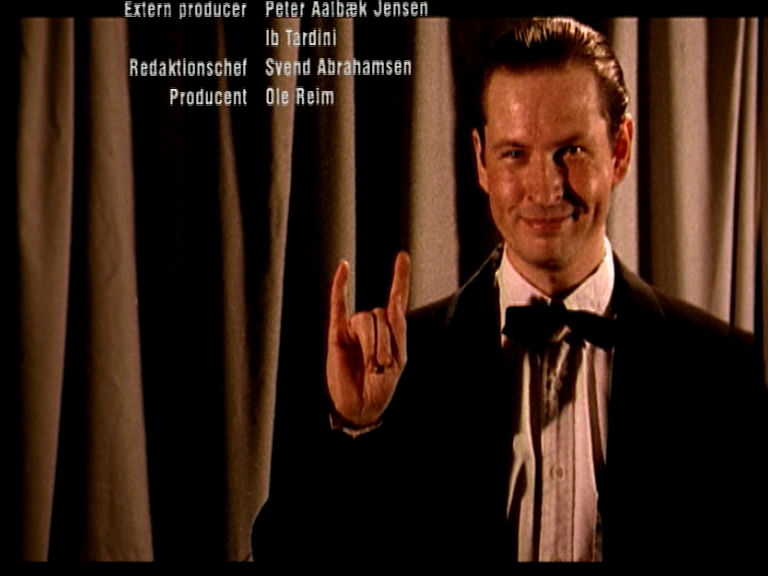

Forging a very direct link to Dreyer, von Trier hired Henning Bendtsen as DP on parts of Epidemic, a collaboration that continued on Europa. Bendtsen, who shot both The Word and Gertrud, was a direct link from Dreyer to von Trier. Later, von Trier cast the actor Baard Owe, who played in Dreyer’s Gertrud, in several of his films. It was also thanks to Bendtsen that von Trier, already the happy owner of Dreyer’s desk and teacup, came into possession of Dreyer’s old tuxedo. Dreyer had bought the tuxedo in 1926 in Paris, when he was working on Jeanne d'Arc. He later gave it to Bendtsen, who passed it down to von Trier. Von Trier wore it in his TV series The Kingdom (1994, 1997), in the short intro and outro sequences where he addresses the audience, making both the sign of the cross and the sign of the devil. Von Trier later donated the tuxedo to the Danish Film Institute.

The Suffering Woman

In the last half of his life, Dreyer was planning to film the great story of male suffering in his famously unmade Jesus film. In the films he did make, the suffering of women is the great, pressing theme. First, in The President, about young women who are seduced and abandoned with tragic results. Then, in Leaves from Satan’s Book, Clara Wieth heroically kills herself. Later, there is the oppressed wife in Master of the House, the Jewish girl caught in a pogrom, in Love One Another, the suffering and death of Jeanne d'Arc, the young woman who falls victim to a vampire in Vampire, the abandoned young woman in the short Good Mothers, Anne and the old woman accused of witchcraft in Day of Wrath, to a lesser degree Inger who dies and comes back to life in The Word, and Gertrud whose uncompromising commitment to love makes her disappointed in men.

Von Trier, too, has delved into this theme in his work. In his early films, however, it seems that the women are largely to blame for their own suffering. This goes for Kim, the prostitute in The Element of Crime, and deceitful Katharina in Europa. Medea, both victim and villain, is a true wronged avengeress. The women in von Trier’s so-called Goldheart trilogy, especially Breaking the Waves (1996) and Dancer in the Dark (2000), come across as innocent victims submitting to martyrdom. Von Trier commented on the influence from Dreyer on Breaking the Waves,

"I do feel that films like Jeanne d'Arc and Gertrud have been important in relation to Breaking the Waves. Dreyer’s films are more academic, of course, more purified. What’s new for me is having a woman at the centre of the story. All of Dreyer’s films have a female protagonist. And a suffering woman, to boot."

The miraculous ending of Breaking the Waves obviously owes a debt to the resurrection climax of Dreyer’s The Word (as well as to Tarkovsky’s Solaris and Nostalghia). But Von Trier’s suffering women change. Grace, in Dogville (2003), is submissive at first, patiently accepting the pain and degradation heaped upon her, but then she has had enough and exacts a terrible vengeance. This character points ahead to the notion of woman as innately evil in the horror fable Antichrist (2009). The film has echoes of Vampire, whose evil vampire is an old woman.

When Dreyer's women are burned at the stake, in Jeanne d'Arc and Day of Wrath (the latter’s Anne ultimately facing a similar fate), it is in the nature of martyrdom and oppression. When von Trier has a woman put to death by burning in Antichrist, it is presented as a necessary act of self-defence by a suffering man.

Careers With and Without Obstacles

In light of the many similarities, it is important to stress a striking difference in Dreyer’s and von Trier’s careers. After the brisk activity of his silent-film years, when he directed nine films in five different countries, Dreyer’s career was beset by obstacles, adversity and failed projects. Dreyer not only focused on martyrdom, he himself was one of the greatest artistic martyrs in the history of film. Over the last 35 years of his career, it was tremendously difficult for him to get to make the films he wanted to make. After the privately financed sound film Vampire (1932) flopped, he did not get to make another feature until Day of Wrath in 1943. He renounced his Swedish production Two People (1945), and over the next 25 years or so he got to direct just two other features, The Word and Gertrud. His pet project, Jesus of Nazareth, was never realised.

Unlike Dreyer, von Trier has met with almost limitless recognition and support in his career. While he did fail to make The Grand Mal, which would have been his second feature, after his debut with The Element of Crime, he has otherwise gotten to do whatever he wants, and the funds to go with it, extending to various bizarre experiments. The reasons he never finished the Kingdom trilogy or the planned American trilogy (Dogville, Manderlay) lie with him. In fact, you might say that is the only real problem von Trier has had in his career. He is not, like his great idol, an unrecognized genius. He is an innovative, controversial and provocative artist who has nevertheless always enjoyed the full backing of the establishment. Crucially, Dreyer and von Trier are connected by their uncompromising will to create great cinema. Inarguably, a straight line – and a spirited legacy – runs from Dreyer to von Trier.

Sources:

Björkman, Stig: Trier om von Trier. Alfabeta, 1999.

Björkman, Stig and Lena Nyman: "I Am Curious, Film: Lars von Trier," in Jan Lumholt (ed.): Lars von Trier Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2003.

Drouzy, Martin: Carl Th. Dreyer født Nilsson. Gyldendal, 1982.

Schepelern, Peter: Lars von Triers film, Rosinante, 2000.

Trier, Lars von: "Om Carl Th. Dreyer," Kosmorama, No. 187, 1989.

By Peter Schepelern | 15 December 2010