We know of several other tantalising, unrealised projects by other great film directors, but this "non-film" was of vital significance to Dreyer’s own life and career. Furthermore, the film has regularly been brought up over the years in the debate that flares up every time a new "Jesus film" comes out. Not infrequently, someone asks, "But, what would Dreyer’s film have looked like? Wouldn’t it have been better?"

We have his screenplay – in several drafts – in English. Add to this, a Danish translation from 1968 and a contemporary translation by Bo Green Jensen for a short-lived stage production directed by Henrik Sartou, now deceased, at the Royal Danish Theatre in 1997.

In the following, I will stick to the original English screenplay from 1949-50.

Dreyer’s first representation of Jesus in 1919

It’s impossible to pinpoint when exactly Dreyer’s idea for a Jesus film emerged, though we do know some of the circumstances behind it.

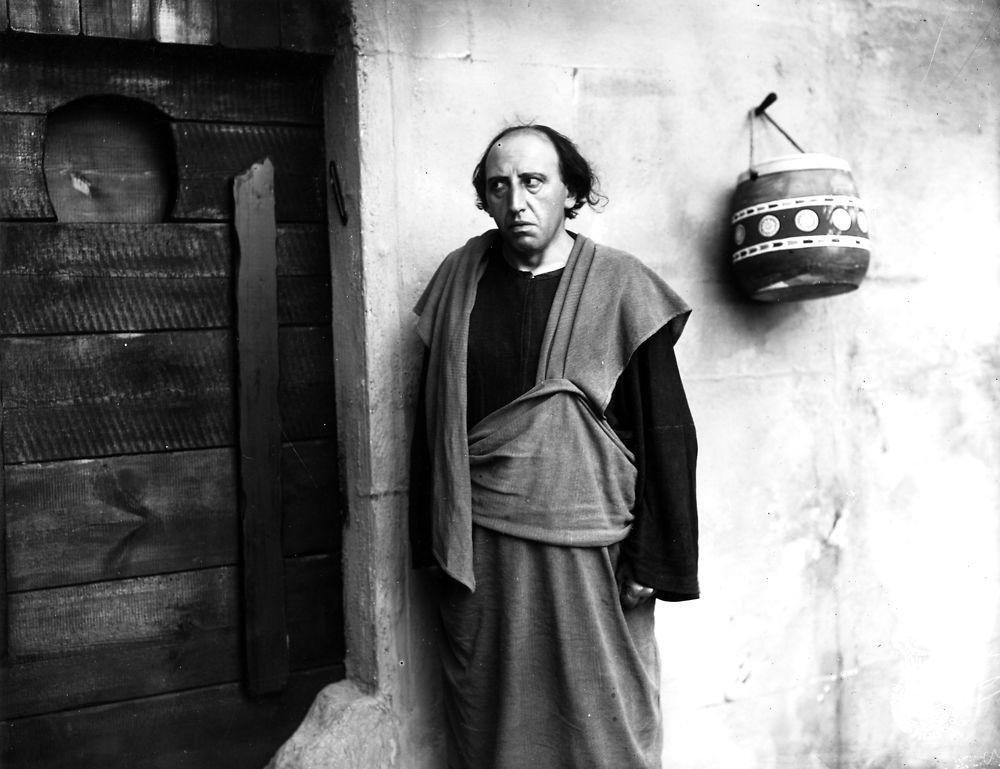

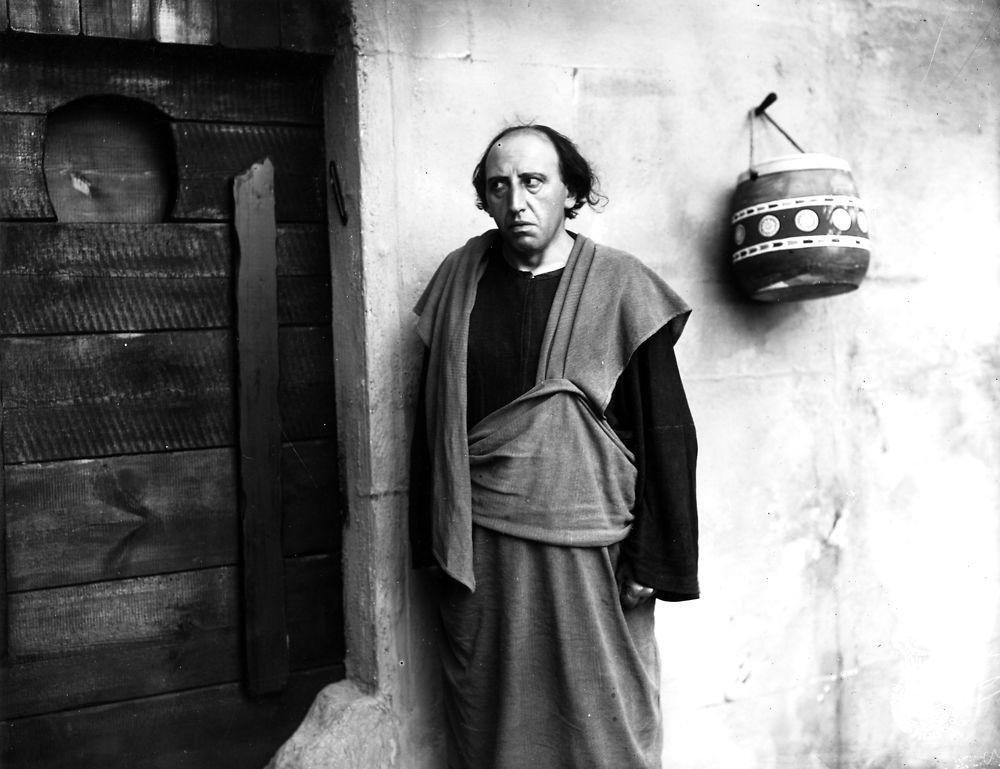

In 1919, Dreyer directed the ambitious and costly Leaves from Satan’s Book, inspired by the American director D. W. Griffith. This film was divided into four episodes, the first involving the arrest and crucifixion of Jesus Christ. The reactions to the film were quite mixed and many people at the time clearly thought that it was highly inappropriate to present Jesus Christ in the figure of a profane actor. To them, it bordered on blasphemy. The Christian daily Kristeligt Dagblad wrote a long indignant review, while Frejlif Olsen, in an enthusiastic review, in Ekstra Bladet related an amusing episode from the premiere where a woman in one of the first rows, in consternation at seeing Jesus emerge on the screen, accidentally set her whole matchbox on fire while lighting a cigarette, the resulting flare causing tumult in the theatre.

It is worth noting here that Dreyer, in a rebuttal of sorts to the Kristeligt Dagblad review, wrote that he had his representation of Jesus closely adhere to convention so as not to offend anyone. But, he added, had he followed his innermost desire, he would have depicted Jesus much more realistically (italics mine), that is, he would have made him much humane. This was exactly what he wanted to realise in his Jesus film.

Dreyer and the Jewish question

Another important circumstance behind the film was anti-Semitism, an issue that increasingly preoccupied Dreyer throughout his life.

In 1921, two years after Leaves from Satan’s Book, Dreyer directed Love One Another in Berlin, which brought him into direct contact with the effects of anti-Semitism. The film is about persecution of Jews. For his cast, he hired Russians Jews who had escaped persecution in their homeland. Their stories made a deep impression on Dreyer, and over the course of the 1930s he met an increasing number of Jews who in one way or another suffered under Nazi persecution. This added the second important element to Dreyer’s Jesus film: Jesus was Jewish!

The event that brought together the different threads and elements in Dreyer’s mind was the Nazi Occupation of Denmark on 9 April 1940. Dreyer says that it suddenly struck him a few days after the Occupation that the Jews at the time of Jesus must have felt like the Danes did now, in 1940: their hatred of the Romans must have been as deep as the Danes’ hate of the Nazis. This set the project of an actual Jesus film in motion. To Dreyer, Jesus’ fate visualised the conflict between the Jew Jesus and the Romans.

Dreyer made other observations about the parallels between the Jews at time of Christ and the Danes in 1940. At the core of what would become his lifelong passion, the Jesus film, was the conflict between those in power and the strong and free man of the mind, the true "freedom fighter." The quotes here indicate that the freedom fighter Dreyer saw in Jesus isn’t a political or revolutionary one, but one who fights against any repression of personal "mental" freedom.

The Jesus of the Gospels

Obviously, any Jesus film – including its script – must relate to the Biblical stories of Jesus, since they are the main sources for our image of Jesus. It is important to point out, however, that the New Testament offers no single unambiguous image of Jesus. The four Gospels were written at different times for different constituencies, and each has its particular intention and focus. Hence, no one would be able to define the "correct" image of Jesus, though the attempt is occasionally made. Some try to piece together an image by rewriting the stories of the four Gospels into a single narrative. Others adhere to one of the Gospels, maintaining that it represents the true Jesus. Further complicating matters, there have always existed fragments of other gospels that did not make it into the Bible, though we have known about them for generations. On some points, they differ radically from the Gospels of the Bible and thus also present a quite different image of Jesus.

Consequently, any artistic representation of Jesus must necessarily draw from the image of Jesus in the Gospels, even though it cannot be evaluated by any objective Biblical criterion: Is this a true or false image of Jesus? Any artist has his or her own intentions and focus. What is important is determining what they are, and that is most clearly accomplished by comparing the artist’s manuscript to the texts of the Gospels.

Dreyer’s corrections: The Jews did NOT kill Jesus

Such a comparison is particularly apt in the case of Dreyer, who attacked this project with passion but also great respect, even awe, for the original New Testament texts. In no way did he seek to profane or reduce or abbreviate the story of Jesus. Even superficial knowledge of Dreyer’s painstaking research – his handwritten notes, his years of Hebrew lessons with Bent Melchior, chief rabbi of Denmark, his intense letter correspondences with Bible scholars, his study trip to Palestine – reveals his uncommon passion and respect for his subject.

However, despite this great respect for the Biblical texts, Dreyer still has a focus that makes certain corrections necessary. As mentioned above, Dreyer urgently wanted to show Jesus not just as a – great and brilliant – human being but as a Jew. Accordingly, throughout the script, Dreyer explains and elaborates the fact that there was no fundamental conflict between the leading Jews and Jesus. The Pharisees that appear in the script are likable and open to Jesus and his preaching. They have their disagreements and discussions, but the tone among these orthodox Jews is amiable. Even Caiaphas, the Jewish high priest, appears receptive. It is "with a heavy heart" that he hands Jesus over to the Romans for prosecution. But being a pragmatic politician, he has no choice.

This is an obvious departure from how the Gospels present the story. There the conflict is clear: the Pharisees plot to capture Jesus and have him killed, while Caiaphas sees in Jesus a dangerous blasphemer. In the Gospels, the leading Jews have a very active hand in confronting and capturing Jesus.

For Dreyer, this "conflict placation" he performs is imperative to show that the Jews did NOT kill Jesus. Here, Dreyer’s political-ideological objective becomes crucial to his understanding of Jesus. Anti-Semitism, which Dreyer zealously fought against until his death, must also be fought through an understanding of Jesus and his times. In Dreyer’s representation, it is important to show that it is the Romans, and the Romans only, who accuse, convict and execute Jesus.

However, a Jewish group appears in the script (more directly than in the Gospels): the Jewish political "revolutionaries." They are a constant element of unrest. It is they who dream of Jesus as a political leader in the struggle against the Romans, and it is they who cause the disturbance in the temple courtyard in Jerusalem, the so-called cleansing of the temple (whereas in the Gospels, it is Jesus himself). Clearly, to Dreyer these are not "true," credible Jews but simple troublemakers.

Jesus – a human being

The second element that is imperative to Dreyer in his portrait of Jesus is representing Jesus as a human being – a singular human being, charismatic and brilliant, by his mere presence, speech and actions impacting his times, and times since, but still "only" a human being. Hence Dreyer’s striking decision to end his story on Good Friday, when Jesus dies on the cross. In Dreyer’s story, there is no Easter morning, no resurrection, no reunion with the disciples and no new beginning. Jesus ends his life as a singular Jewish man who dies for the spiritual freedom of his people.

Dreyer largely follows the chronology of the Gospels: from Jesus’ introduction by John the Baptist to his crucifixion at Easter. Dreyer likewise by and large sticks to the episodes from the Gospels, while gathering the generally rather fleeting and scattered narrative strands from the New Testament into a few striking stories. He has no need to reimagine the figure of Jesus outside a Biblical context. He gathers and focuses. Of course, the emphasis of some of the stories accordingly shifts.

Two key locations: Peter’s house and Bethany

Two crucial and unifying locations in Dreyer’s script are the disciple Peter’s house and the house at Bethany where Jesus’ close friends Mary, Martha and Lazarus live. The Gospels briefly mention the event in Peter’s house, where Jesus heals Peter’s mother-in-law. Dreyer’s script unfolds the story much further. We meet Peter’s wife and mother-in-law afterwards as well, including as they work in the kitchen, preparing and serving dinner to Jesus and his disciples. Moreover, Dreyer also uses this house as a gathering place for the people who want to hear Jesus speak. The Bible mainly mentions Bethany in connection with the raising of Lazarus and there is no follow-up, but in this case as well Dreyer presents a larger, interlocking story and we meet Lazarus several times after his miraculous raising.

Dreyer’s focus on miracles

Particularly striking about these stories, and the script overall, are the miracles Jesus performed, acts of healing that seemed miraculous in his day. Indeed, he even raised the dead. It is interesting that these miracles are crucial to Dreyer in creating a portrait of Jesus. Jesus possessed a singular spiritual power capable of releasing the forces that bound the sick to their illnesses.

While Dreyer was writing the script, a debate was raging in theological circles about miracles. Dreyer was familiar with this discussion. The issue was so-called demythologising. A leading figure in the debate was a German theologian, Rudolf Bultmann, who endeavoured to "release" the stories of Jesus from their mythological character. To Bultmann, the miracles were not compatible with a modern consciousness – what they did have was symbolic significance, a special way of narrating Jesus’ unique status. To understand these miraculous tales you had to go behind the image, behind the symbol, to the actual teachings of Jesus. To Bultmann, the miracles were more a tool of interpretation more than events that had actually occurred.

Dreyer was familiar with this debate, but the miracles are clearly crucial for him as a way to understand Jesus and the impact he had. For Dreyer, it was not necessarily a matter of explaining away the miracles but of understanding them as real events, albeit viewed with a modern mindset. In several director’s notes, he describes how Jesus is able to use his special spiritual powers to "resurrect" the lifeless soul of the sick person he is facing.

Dreyer’s view of Pilate, Caiaphas and Judas

Though Dreyer makes the important points that Jesus is a loyal Jew and his controversies with the Jewish leaders are open discussions within a common framework, the tone of the screenplay sharpens as it progresses. This happens when Jesus "expands" the Jewish consensus, for instance by teaching his message of universal love – a message that breaks the boundaries of the traditional Jewish understanding of brotherly love. More important, however, the Romans, led by Pilate, regard Jesus as a troublemaker, another Jewish rebel.

Thus it is that the high priest Caiaphas "with a heavy heart" hands Jesus over to the Romans – to save the Jewish people! Better to sacrifice one person for the sake of the people than run the risk of the Romans, once again, punishing the entire people because of this one rebel! Dreyer views Caiaphas as a rational pragmatist. In that context, he concludes that Jesus is one in a long line of idealists who have laid down their lives for "pragmatic reasons."

As another effect of this unambiguous confrontation with the Romans, Dreyer entirely leaves out the story of Barabbas, which is so important in the Gospels – the story of how, on Good Friday, Pilate has to choose between the political revolutionary Barabbas and Jesus. To Dreyer, Pilate has just one enemy: the Jew Jesus.

The Gospels give Judas no clear rationale for betraying Jesus, while Dreyer’s script adds a few nuances. A loyal disciple of Jesus, Judas has a task to perform. He and Jesus both consider this task to be "God’s will." His so-called betrayal is, so to speak, to act as a tool of God. Judas is the one who definitively seals Jesus’ fate: to die for his principles, his eternal thoughts.

The great passion

As mentioned, it is evident from everything Dreyer wrote and said that this was the film he wanted to make. One can wonder how he managed to maintain his passion over the years, but there can be no doubt about his burning desire to make this film even up to the time of his death. We will not discuss Dreyer’s financial problems here, though they clearly wore on him, and still he maintained his ambition. One reason why the project kept falling through was that Dreyer was a man of his own head and made (perhaps unrealistically) big demands. The film had to be shot in Israel with a Jewish cast and it had to be in Hebrew/Aramaic. Moreover, he wanted the film to premier in Israel.

The Word and Gertrud as exercises in style

Meanwhile, Dreyer continued making world-class films. However, if you read him closely, you almost get the impression that the films he made, The Word and Gertrud, were "mere" exercises of sorts for him – or, attempts to filmically work out some of the complicated problems of form he knew would emerge when he made his Jesus film.

His adaptation of Kaj Munk’s play Ordet would be a test of how to give valid filmic form to a resurrection. In Gertrud, Dreyer employed a singular "theatrical" style that could also be used to represent characters, speech, scenes and so on in a Biblical film. This impression of his films as exercises in style is, of course, a colossal reduction of the actual films and their qualities. Yet I take the liberty of mentioning it here, because there are real indications from Dreyer to support that assumption.

From screenplay to manifesto

Another important reason why Dreyer was able to maintain his passion in the face of so much adversity was that the script in a way became a "manifesto" of sorts for him. From the 1950s and up to his death, Dreyer thundered against anti-Semitism. An unconditional supporter of the state of Israel, he was several times honoured by Zionist organisations. In his script, he even directly compares the Romans at the time of Jesus to the Nazis. We also know from countless letters that, every time there was political unrest in the Middle East, he wrote that now was the right time for his film, because it would be a welcome statement in a politically inflamed situation.

So, even as the project kept being out of his reach, Dreyer to the very last maintained his hope of realising the film, for artistic as well as for more ideological-political reasons.

In conclusion

A screenplay is not a film, of course. Though Dreyer in the script provides many and, at times, detailed guidelines for shaping the individual scenes, we are left with nothing but conjecture regarding the potential end product. Still, the script not only offers a window into Dreyer’s passion of many years – this very film – it also offers a window into the worldview of a great (conservative) and single-minded artist and humanist. As I see it, the following conclusion must be made: if you want to understand Dreyer as an artist and a person, there is no getting around a thorough reading of this script and a reflection on its singular position in his life and work.

By Jes Nysten | 05. July