Just as a sculptor takes a lump of marble, and, inwardly conscious of the features of his finishedpiece, removes everything that is not part of it – so the filmmaker, from a “lump of time”made up of an enormous, solid cluster of living facts, cuts off and discards whatever he does not need, leaving only what is to be an element of the finished film, what will prove to be integral to the cinematic image. [1]

I: Sculpture encounters Photography

It is a curious historical fact that the first person in Denmark ever to sit for a photographic portrait was the sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen. The resulting daguerrotype, held by the Thorvaldsen museum in Copenhagen, is dated to 1840, that is, within a year of the first public demonstration of the new technique. It shows an old, tired-looking Thorvaldsen, posing in a garden beside one of his reliefs. As Stig Miss comments in his introduction to Marie-Louise Berner’s book on the daguerrotype of the sculptor, ‘it is remarkable that Thorvaldsen, by putting his own likeness at stake, ushered in a new visual realism, which over the course of the nineteenth century would, with increasing force, disavow his own art.’[2] By a quirk of over-exposure, this disavowal of sculpture by photography already seems to be enacted by the obliteration of the relief sculpture beside which Thorvaldsen is posing in the photo. Meanwhile, every detail of the leaves behind him (on what, given the exposure time required, was clearly a still day) has been captured for posterity in the daguerrotype’s alchemy of silver and mercury.

From the position of Thorvaldsen’s own hand in the daguerrotype, there is reason to believe that he himself was conscious of the perilous significance of this first encounter between the two art forms of sculpture and photography in Denmark. Thorvaldsen is making the Italian corno gesture, the first and little fingers extended from a clenched fist. Was the corno simply meant to ward off the evil eye that might steal his soul during exposure to this unfamiliar technology? Or does it imply that Thorvaldsen sensed that the medium of photography, in its instantaneous, quasi-indexical registration of the play of light on the world, would usurp the function of sculpture to fix an impression of material reality in the face of ephemerality and death?[3]

A.C.T. Neubourg: Thorvaldsen, 1840, daguerrotype. With kind permission Thorvaldsens Museum.

A century later, Carl Th. Dreyer again brought Thorvaldsen, or rather his sculptures, before the gaze of the camera, this time to make a short film to mark the 1949 centenary of the Thorvaldsen Museum. The Thorvaldsen film is one of two works directed by Dreyer that I will be discussing in some detail in this essay as films which seem to engage with sculpture as a challenge for the cinema; the other is Michael ( 1924). I will also briefly mention Ordet (The Word, 1955) and Gertrud (1964).

This is part of a larger project that explores Dreyer’s relationship to the arts and to the concept of the museum, and my intention here is not to offer an exhaustive survey of sculpture in Dreyer’s oeuvre. Neither is this essay about the oft-observed sculpturality of many of Dreyer’s human bodies. Rather, I want to explore how sculpture in Dreyer’s cinema, at times, serves to pose questions about film art, about the nature of the film medium (the ontology of the image), and about the relation of the embodied viewer to the material object captured on film. If the Thorvaldsen daguerrotype literally and symbolically obliterates the sculpture, Dreyer and his cinematographers reveal and re-animate the texture and topologies of the reliefs and sculptures they encounter.

II: The close-up as painting and sculptural relief

Much attention has been lavished on the presence and play of other forms of art in the films of Carl Th. Dreyer. Of particular note in recent years was the exhibition Hammershøi>Dreyer: The Magic of Images, jointly mounted in late 2006 by Ordrupgaard Museum in Copenhagen and the Centre for Contemporary Culture in Barcelona. This exhibition traced the influence of the Danish painter Hammershøi’s interiors and landscapes on Dreyer’s oeuvre, testing out the Danish critic Poul Vad’s declaration that Dreyer was Hammershøi’s one true heir.[4]

In her introduction to the exhibition catalogue, the curator, Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark, touches on what she calls the ‘scenographic’ problem of exhibiting painting and film alongside each other, within the same ‘exhibition universe’.[5]There is a danger that film as a strong and attractive medium might steal attention away from the paintings, for example. The solution adopted at Ordrupgaard was to play five-minute segments of several of Dreyer’s best-known feature films on a loop: Inger’s funeral and resurrection in Ordet, for example, and the young apprentice’s painting of the model’s eyes in Michael.These were projected onto a screen separated from the paintings and rest of the room by a thin curtain of white muslin.[6]

In the sequence from Michael screened in the exhibition, the Master struggles to complete a portrait of the beautiful young Countess Zamikow. Unable to capture the likeness of her eyes, he allows his protégé, Michael, to attempt to complete the portrait, a task in which Michael succeeds. The sequence depicts the creative process via much the same rhythms that pervade the rest of the film: crosscutting between close-ups of the Countess’s shimmering, quivering face, and the alternately panicked and concentrated faces of the men trying to paint her. This cinematic account of portraiture, in other words, self-reflexively gestures to the similarities and differences between painting and film (a move presumably not lost on the exhibition organisers and visitors): the facial close-ups are composed and lit in the manner of the Dutch masters, but the faces are just animated enough to attest to their instantiation on film.

Indeed, the film scholar David Bordwell argues that Michael constitutes an extreme example of Dreyer’s propensity to separate face from tableau in his films; in Michael, he argues, the objets d’art that populate the space of the film are devices that emphasise the filmic interplay between faces on the one hand, and tableaux on the other.[7] We can thus see Michael as the point at which Dreyer’s early treatments of the facial close-up, simply adaptations of the ‘anthropocentric concerns of the classical style’,[8] begin to crystallise into the distinctively Dreyerian close-ups of La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928) and later films.

Complicating things further, this, like the other film sequences in the Ordrupgaard exhibition, was set to play on a loop, the faces caught in what, with successive viewings, begins to resemble the series of almost-still photographs – as opposed to the properly cinematic – that Eisenstein and others saw in Dreyer’s work.[9] Drawing on Laura Mulvey’s recent work on the effect of the digital revolution on the relationship between the still and moving image, we might muse that the digital technology that facilitates screening such sequences on a loop, using a small data projector, enables (or even forces) us to re-think not only our understanding of the interplay of narrative and image, but also the distinctions between still and moving image. Mulvey writes:

[A]t the end of the twentieth century new technologies opened up new perceptual possibilities, new ways of looking, not at the world, but at the internal world of cinema. The century had accumulated a recorded film world, like a parallel universe, that can now be halted or slowed or fragmented. The new technologies work on the body like mechanisms of delay, delaying the forward motion of the medium itself, fragmenting the forward movement of narrative and taking the spectator into the past.[10]

Played on a loop, a certain idea which is already present in Michael is emphasised: the oscillation in this film between static facial close-ups and the logic of the painted tableau turns the sequence into a meditation on the capturing of real-world objects, or faces, by the painter’s hand. As a corollary, our attention is drawn to the difference between the indexical registration of the world on (analogue) film, versus the interpretation of the object on canvas through the mediation of the painter’s (fallible) hand and eye.

This important difference between painting and cinema is clarified if we appeal to film theorist André Bazin’s famous essay The Ontology of the Photographic Image, in which he muses that the origins of the plastic arts lie in the desire to preserve the body:

If the plastic arts were put under psychoanalysis, the practice of embalming the dead might turn out to be a fundamental factor in their creation. The process might reveal that at the origin of painting and sculpture there lies a mummy complex.[11]

For the ancient Egyptians, Bazin goes on, the corporeal bodies of the dead must be preserved at all costs; as extra insurance, terracotta statues were placed in the sarcophagi, lest the mummified bodies were destroyed or stolen. This was a Plan B, we might say, being only a ‘preservation of life by the representation of life’.[12] Bazin goes on to show how mummification and the terracotta statuettes stand for two strands of art’s reponse to the real through the ages: on the one hand, ‘the duplication of the world outside’ (the mummified bodies), and, on the other, ‘the expression of spiritual reality’ (the terracotta statues).[13] Cinema and photography have freed the plastic arts from the first of these tasks, leading to a crisis of realism in the plastic arts in modern times.[14]Roland Barthes, in his last book, La chambre claire (Camera Lucida, 1980), was adamant that the same quality of objective indexicality could not be attributed to the cinema – only to still photography, in which the subject has the quality of that-has-been and the presence of the dead loved one’s body is recorded by the light that emanated from it and now ‘touches’ the viewer.[15] But for Bazin, the ‘impassive lens’ of the cinema can capture the duration of things, such that the cinema can be described as ‘objectivity in time’ and ‘change mummified’.[16]

Painting is the ‘plastic’ art on which Bazin draws in order to emphasise how different is the mechanical, nonhuman genesis of photographs. While the essay mentions sculpture as one of the plastic arts, the Egyptian terracottas are the only sculptures actually discussed by Bazin. However, in an intriguing little footnote, he compares the indexical quality of photography to that of the moulding of death-masks: both art forms, he says, ‘involve a certain automatic process’ and ‘the taking of an impression’.[17] The photographic arts, then, are the inheritors of the art of the embalmer.

The iconic sequence in Michael which charts the struggle of the painter’s hand to capture the likeness of the Countess, then, casts (pun intended) the close-up in the role of the death mask (or indeed life mask): by cross-cutting with the inadequacy of portraiture in oils, the film flaunts its basic ontology, which is to capture the face as it is. Its ability to capture even the ineffable quality of the Countess’ eyes is implied by the reflected light sparkling in them. The film’s stylistic signature of disembodied faces shimmering in dark space intensifies the allusion to the close-up as indexical impression of a real face.

Furthermore, the logic of the comparison between the ability of cinema and painting to capture mortal flesh is, I think, crystallised in the form of a sculpture which appears early on in Michael.

III: Dreyer’s Venus

If the technology described by Mulvey and its effects are new, the ability to fragment, capture and reproduce iconic images from the cinema is rather older. The film Michael also supplies the cover image for David Bordwell’s seminal book The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer,[18] driving home, again, the significance of the art work in the cinema of this director. In this shot, the camera is positioned behind and above a man and a woman who are gazing at each other, their profiles illuminated by the reflected light from a statuette they are cradling between them. Bordwell discusses this scene as an example of how Dreyer, in Michael, ‘projects the characters’ erotic drives onto their aesthetic tastes’.[19]As established above, this is typical of Michael: in this shot, too, the twin faces of the characters seem to float luminously in the darkness of an undefined space, the effect intensified by the use of a round iris.

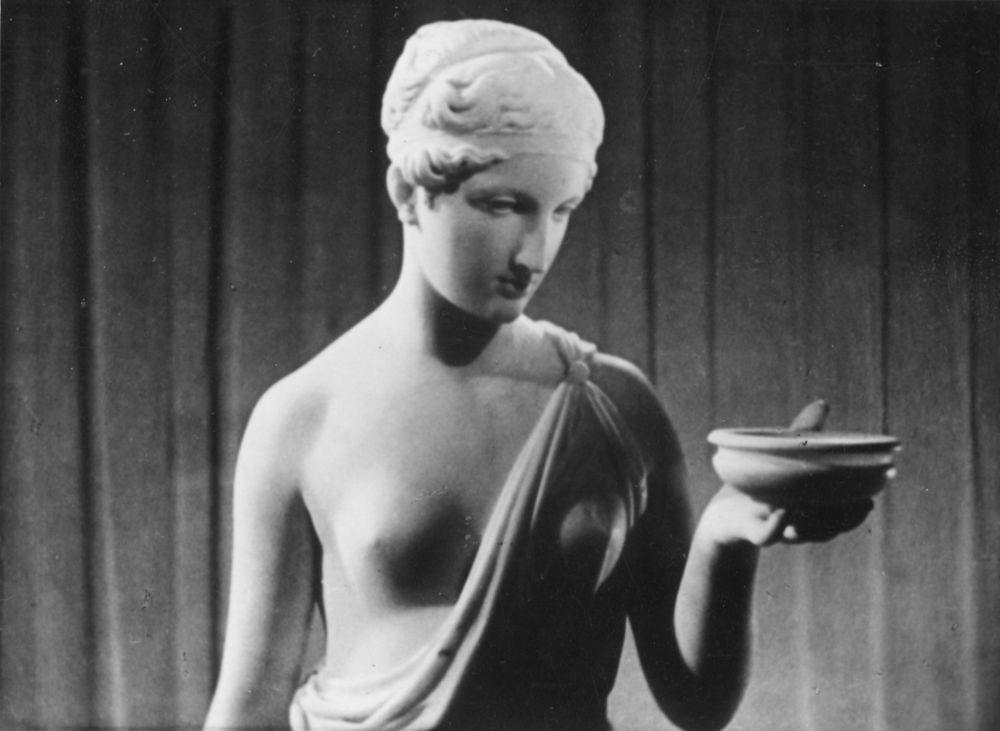

What holds my attention (and, invariably, that of my students) about this book cover is not the faces bathed in reflected light from the little objet d’art held by the lovers, but the statuette itself. The play of shadows reveal the womanly curves of its small breasts, shoulder, inner thigh and pudenda, but, in the manner of the Venus de Milo, the statuette has no arms or head. Like the free-floating, luminous, creamy-skinned human faces that people the film, the statuette is radiant, but matte. In one sense, this shot is a Dreyerian close-up, predicated on the tension between the painting, the still image, and the moving image. On another level, though, the presence of the statuette introduces another tension into the composition: the two-dimensionality of the screen is comparable to that of a painting, but what can cinema say of sculpture, or indeed of its own relation to sculpture?

This, as we shall see, is a question that was to exercise Dreyer and his collaborators, twenty years later, when planning the short film Thorvaldsen. However, we can also make some tentative observations within the context of Michael. Firstly, the circular frame formed by the faces and shoulders of the lovers in this shot keep us, the viewers, outside the sphere of contact with the art work. At the same time, the lovers do what one is not allowed to do in a museum: they are touching, cradling, caressing the object. The objet d’art is on display in its own well-defined spatial arrangement, as are the numerous other paintings and sculptures in Michael. However, this particular object is imbued with a certain tactility; the viewer touches it by proxy, and is thus moved to imagine its texture, shape and weight. One might be tempted to say that the lovers-to-be cradle the object with tenderness, with trepidation, as they might their newborn baby; but the erotic investment in the statuette is rendered unambiguous when they are called to dinner and the object, now replaced on a side table, is given a final caress by a male hand.

The treatment of the statuette is so exceptional within Michael that it seems to open up a third possibility in the film, over and above the dialectic between face and tableau that Bordwell emphasises. If Dreyer’s early films tend to ‘clip the face free of its surroundings’[20] in close-ups, this results in sequences in Michael where, he muses, even characters in conversation seem to be floating in different universes, while, at the other extreme, long-shots of the interior of the Master’s house stress ‘the enclosure of art objects within the huge rooms’.[21]But, with the statuette, here we have an object which can be apprised by touch; we enter what Bogh calls the intimsfære or zone of intimacy of the art work.[22]This play with the conventions of interaction with a sculpture is, as we shall see later, fundamental to Dreyer’s approach to filming sculpture.

There is one other peculiarity inherent in this statuette: the absence of head and arms suggest that it is a plaster reproduction of a damaged classical sculpture, rather than an original work in its own right.[23] In fact, it is recognisable as a Medici Venus, which can be seen in the Metropolitan museum of Art, New York. This same torso is the subject of an essay by the present-day sculptor Edward Allington, who writes of the statuette:

It’s a female torso: no arms; no legs; no head. The body is bent forward a little, making the curve of the belly prominent. The hips are square and full, the buttocks smooth, the breasts slightly rounded domes like the insides of wine glasses – let me tell you, it’s pretty damn sexy.[24]

Allington’s installation Roman from the Greek in America (1987) comprises a number of plaster casts of the Medici Venus, playing with the statuette’s status as a modern reproduction of a Roman copy of a Greek original; ‘a copy of a copy of an original only “presumed” to have existed’.[25] For Allington, the Medici Venus prompts reflection on how processes integral to sculpture – clay models, mouldings, castings – ‘deny the artist’s touch’ and are thus reminiscent of cinema production:

The sculptor’s vision is realized through collaborative effort. You might say that the sculptor’s role may be likened to that of the cinematic “auteur” or a composer of music. In this light the current liking for sculptors’ drawings becomes immediately understandable, for in them at least the artist’s touch is guaranteed.[26]

As we shall see, Dreyer, too, seems to have been interested in the sculptor’s drawings. For the moment, we can observe that the mode of production associated with this model in Michael marks it out from, and thus emphasises by juxtaposition, the discernibly original tableaux and portraits we see the painterly genius struggling with in the course of the film. And, perhaps, its status as a copy of an older original gestures to the mortality of the cursed lover holding it, as well as that of the Master himself.

In lingering on the sensuous encounter of the doomed lovers with their moulded plaster statuette, Michael, I want to argue, gestures to the propensity of film to embalm the dead, to preserve the body that once lived and moved and loved. That the hand that caresses the statuette belongs to the would-be suitor – who is cursed to die if he knows true happiness – drives home the paradox that the sensual pleasures of life and the mortality of the flesh are but two sides of the same coin, as does the concluding juxtaposition of the slow stilling of the Master’s dying breaths and the final shots of Michael being cradled by the Countess.

IV: Dreyer’s Thorvaldsen

In Thorvaldsen (1949), a similar set of productive tensions between cinema as moving image and its cognate artforms are crystallised.

In summer 1947, Dreyer wrote to the head of Dansk Kulturfilm, Ib Koch-Olsen, to suggest a short film about the sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1848).[27]Dreyer’s rationale was to film Thorvaldsen’s most popular and most ‘accessible’ works, so that the man in the street would be better able to appreciate what was special and unique about Thorvaldsen’s art. Incidentally, this motivation corresponds to André Bazin’s argument for the importance of the art film: ‘to bring the work of art within the range of everyday seeing so that a man needs no more than a pair of eyes for the task’.[28] The arguments raised against Dreyer’s proposal amongst the committee that evaluated the project, and, later, in the popular press once the film was made, are also echoed in Bazin’s discussion: that film as a medium ‘does violence to’ the plastic arts, and that the ‘artificial and mechanical dramatization’ that film can impose on a work of art might ‘give us an anecdote’ and not a painting or sculpture. On the other hand, the strange fusion of the two art forms can provide the work of art ‘with a new form’ of existence, making an ‘aesthetic symbiosis of screen and painting’.[29]Ultimately, Bazin makes the point that the aesthetic success of art films is dependent on how well informed and sensitive the filmmaker is.

Dreyer was certainly well-informed about Thorvaldsen. In her archival research, Britta Martensen-Larsen outlines Dreyer’s preparatory work on the Thorvaldsenfilm, and brings to light some of the contents of his original manuscript for the commentary. This was, Martensen-Larsen reports, eventually trimmed by around half on the insistence of the co-credited director, Preben Frank, and so the public was never exposed to Dreyer’s complex and fascinating narratives around Thorvaldsen’s sculptures (to which I shall return in a moment). The Thorvaldsen film had to stand or fall on the basis of the cinematography, and Dreyer himself did not regard the film as a success. Dreyer and his collaborators filmed at the Thorvaldsen Museum in the heart of Copenhagen in summer 1948, and the project was more or less complete by the time of the museum’s centenary celebrations in mid-September.

The museum had opened around the time of Thorvaldsen’s death in 1848; its layout and the works exhibited remain, even today, more or less as they were in the nineteenth century. For Dreyer’s film, those statues that were to be filmed had been moved from their plinths and into the entrance hall. There, a grey curtain had been hung as a backdrop, and the works were mounted on a revolving plinth and lit by spotlight. This was intended to maximise the space around the sculptures – necessary in quite a compact museum – which, as Martensen-Larsen puts it, ‘strengthened the plastic effect’ of the sculptures.[30]It also enabled the camera to get close up to the sculpture and move over its surface, lingering on ‘the essential details of the human anatomy’.[31] Other works, such as reliefs, were filmed in situ.

What is immediately puzzling, however, is the decision not to film the space of the museum itself, which had been ingeniously designed to imitate a sculptor’s atélier and meticulously planned to stage the encounter of each sculpture with the visitor and with the available daylight.[32] We might speculate that the museum’s innovations in its use of daylight – the use of black lead cames in the windows results in a spotlight-effect directed at each statue, for example – produced unfeasible filming conditions. But the decision to remove the sculptures from their established spatial context and re-situate them in as featureless a filmic space as possible also suggests that Dreyer’s usual interest in the inhabitation of space by his subjects[33] is not to the fore here; rather, the interest lies in the space of encounter between sculpture and viewer.

I would like to suggest that we can understand Dreyer’s Thorvaldsen as appealing to a sense of touch – or rather the missing sense of touch that film cannot provide. This is a key idea in Laura Marks’ influential book from 2000, The Skin of the Film. Some films, usually, but not always, minor, experimental, and intercultural works, radically dislodge vision as the reigning sense. They ‘appeal to the sense that they cannot technically represent’[34] such as touch, taste and smell, in order to find ways to express experience and memory that are not completely encoded in the dominant narratives and images of Western culture. What film can do is gesture to what it cannot do; it can approach touch asymptotically, and evoke ‘tactile forms of knowledge’.[35] Here, we have to think of the viewing experience – of both sculpture and film – as embodied. Marks regards the viewing experience as not purely visual but as ‘an extension of the viewer’s embodied existence’.[36] The senses, and sense memory, help to create the meaning of the film.

In the case of sculptures, of course, the visitor is generally not allowed to touch. From behind the cordon or from a respectful distance, the museum visitor explores the sculpture visually as a three-dimensional object. But the cinematography in the Thorvaldsen film invests the sculptures with a dynamism that is not attainable for the embodied museum visitor. For example, the camera moves around sculptures that are revolving on a plinth; the Dreyerian slow horizontal pan is translated into a sensuously slow close-up shot tracing the lines of sculptures from top to bottom and upwards again; and lavish use of dissolves superimpose the lines of one sculpture on another. What is being evoked is perhaps not the sensory and spatial experience of being in the museum, but, rather, the visitor’s longing to touch the forms of the marble and plaster, to experience the cold texture of the surfaces. Thus the synthesis of film and sculpture activates a sensory experience of Thorvaldsen’s sculpture which is not attainable by the museum visitor.[37]

We could go further: it could be that Dreyer’s engagement with the sculptures gives us a Thorvaldsen that is unrecognisable to an art historian. Thorvaldsen’s weakness is usually said to be his ‘coldness’. For example, the art historian Licht, reviewing Thorvaldsen’s influence in nineteenth and twentieth century sculpture, comments:

Thorvaldsen is far more anonymous [than Canova] in his treatment of surfaces and masses. The perfection of a composition, the utmost clarity of design, the scrupulous exclusion of private, idiosyncratic emotional responses make the sheerly sensuous appearance of his sculptures a matter of indifference. One is often tempted to caress a Canova, but rarely does one care to come too close to a Thorvaldsen, whose even surfaces and slightly flaccid volumes never appeal to a muscular, haptic or visceral response on the part of the spectator. [38]

This difference in style between Canova and Thorvaldsen has been attributed both to the generational and religious chasm between them (Canova was thirteen years older) and to the latter’s Italian origin.[39] But it seems that Thorvaldsen was consciously and determinedly resistant to the Baroque practice of establishing an erotic and affective connection to the beholder:

Thorvaldsen definitely did not wish to excite the spectator and was not at all interested in the swooning gaze and the thumping heart. On the contrary, the act of viewing could never be too peaceful, contemplative and idyllic […] Thorvaldsen wanted […] to avoid completely a desiring relationship to the sculpture. No, the best thing was to imagine the sculpture as alone unto itself, completely apart from any presence of any kind.[40]

The figures seem to be alone in an untouchable intimsfære or zone of intimacy. This has been argued to herald the coming of a bourgeois subjectivity in which the boundaries of the individual subject stopped at the skin, and identity turned inwards.[41]

From the shoot of Gertrud in Vallø Slotspark - Nina Pens next to Venus. Photo:

Else Kjær.

At this juncture, it is instructive to compare briefly the engagement with the sculptures in Thorvaldsen with Dreyer’s (perhaps) most famous statue, the Venus in the park in Gertrud. During Gertrud and her young lover’s first dialogue in the park, they are positioned in the foreground, with the sculpture to the left of the frame, in the background of the composition. The apparent intimacy of the lovers’ pose is thus tempered both by the clear, sterile space around the statue, and by its stony stasis in juxtaposition with the slow-moving, organic intertwining of their caresses an the surrounding nature. In the second rendezvous in the same location, Gertrud is first positioned sitting on the plinth with her back to the statue, and then strolls away from it, so that the sculpture remains out of shot, but very much ‘present’ in the scene. Again, it is the distance from the sphere of intimacy of the sculpture of Venus that is meaningful for the lovers, here negotiating the end of their affair. The resolutely optical, as opposed to haptical, engagement with the Venus figure encodes Gertrud’s self-imposed spatial and emotional isolation in defiance of the venusian desires of the flesh.

In his original script for the Thorvaldsen film, which was, as noted previously, radically trimmed down by Dansk Kulturfilm, Dreyer also acknowledged this apparent coldness, but saw in some of Thorvaldsen’s masterpieces the sublimation of just that ‘private, idiosyncratic’ emotion which Licht and others miss in his sculpture. Echoing his own idiosyncratic vocabulary in his writings on film, Dreyer reads ‘rhythm’ into certain of the sculptures, a rhythm which, he thinks, releases the feelings which Thorvaldsen worked into his sculptures and reliefs. For example, in the part of the original manuscript that deals with the sculpture of Priamus, Dreyer writes the following:

In this work, as in all of Thorvaldsen’s art, it is the rhythm that delights. He had a gift for bringing together the movements of the figures into rhythmic […] harmonies. This rhythmic musicality is Thorvaldsen’s most essential genius. He demonstrates it in its purest form in the relief of Priamus. The facial expressions, as usual, say nothing – they must not distract attention from the articulate rhythm.[42]

In several of the commentaries, Dreyer reckons that Thorvaldsen was working his way out of a melancholic mood. This is not just sculptural lyricism, he insists: these sculptures are human documents.[43] If Dreyer sees a rhythm in the sculptures themselves, though, others have seen in film the possibility of ‘reanimating’ the ‘stillness’ of statues, as Mulvey puts it in connection with Roberto Rossellini’s footage of classical sculpture in his Viaggio in Italia (1953). Rossellini releases the sculptures from the ‘frozen moment’ that they capture.[44] In Dreyer’s film, this is not the case; he sees rhythm and movement already in the sculptures – both in their composition and in the bodily work that was put into the reliefs – and works to release it for the viewer. His film creates movement by, firstly, substituting camera movement, interacting with the movement of the revolving plinth and the consequent chiaroscuro effect of the play of shadows, and thus animating the sculptures; and, secondly, by ‘moving’ the viewer affectively through lulling her into the stroking, circling motions of the camera’s encounter with the statues.

V: The artist’s touch: Thorvaldsen’s hands

This second task depends not so much on establishing Thorvaldsen in the voiceover as a human being whose veins run with ‘warm, living blood, and not fish blood’[45] though this is certainly part of Dreyer’s strategy. It is more a matter of encouraging the viewer to use the camera as a prosthetic finger; to feel with their eyes the topology of the sculptures, a facility which Laura Marks develops at some length in her notion of haptic cinema in The Skin of the Film. Arguably, the film switches between haptical and optical visuality in its oscillation between establishing shots of the work as a whole, and its extreme close-ups, usually flowing up and down the limbs of the sculpture, of only-just-identifiable body parts. What is also interesting is the almost complete absence of any texture on the surface of the sculptures. The perfect smoothness is in itself a haptic field. To create these effects, the film has to enter the intimsfære(Bogh) of the sculpture and break through its self-contained composition to linger closely on limbs and breasts and necks – less so on faces, because, as Dreyer repeats insistently, the emotion is not in the faces. For example, in Venus, ‘we will see that there is absolutely no love to be seen in her face. But there is so much more in her torso, which is full, lovely and, behind the modesty, quite shivers with inner warmth and life.’[46]

There is a curious moment in the last thirty seconds of the film which survived the cuts, a moment where Thorvaldsen’s and Dreyer’s respective oeuvres seem to gesture to each other, even, we might muse, reach out to touch hands, across the boundary between the mediums of sculpture and film. Allington’s comment on the compelling appeal of sculptor’s sketches as the indexical trace of his hand is apt here, for Dreyer makes a point of visualising the translation of Thorvaldsen’s sketches of a sculpture’s hands – appropriately enough – into the finished statue.

Specifically the Thorvaldsen film concludes by moving out of the sphere of intimacy constructed around the sculptures and real space, into Vor Frue Church in Copenhagen, to show the sculptor’s most famous work, the Christ, in the context for which it was designed. Our attention is drawn to the particular composition of the statue’s arms and hands; Thorvaldsen conceived the distinctive, beckoning pose only after considering several other gestures, including ‘arms outstretched or raised to heaven, blessing or praying’, the voiceover tells us. The creative process of finding the right position for Christ’s hands and arms is enacted in the film by a series of dissolves. A long shot of one of the apostle sculptures in the church dissolves into a shot of an armless sculpture – a nod to the classical sculptural heritage, superseded here by the persistence of the nineteenth-century advent of the artist-as-genius? – which in turn is superimposed, by way of a dissolve, onto one of Thorvaldsen’s exploratory sketches of Christ with one arm raised and a finger pointing heavenwards. This, finally, dissolves into the film’s penultimate shot, a medium shot of the Christ sculpture, the position of its arms emphasised by the shadow of the hands cast on the wall behind it; this insistent emphasis on the hands is shared with the subsequent long shot of the same scene, as the film fades to black. The skilled hands of the sculptor, their traces embedded in his sketches, are thus doubly inscribed by the palimpsest of sculptor’s hands and sculpture’s hands on screen.

The distinctive pose of the Christ statue is echoed – indeed, imitated – in Ordet(1955) in the person of Johannes, who positions his arms in almost exactly the same way for his sermon on a grassy dune. Here, at the end of this essay, we return to Ordrupgaard Museum in 2006, where the end of Ordet is playing, like the sequence from Michael, over and over. Weeping at his wife’s coffin, Mikkel refuses to be comforted by the thought that her soul has departed; he cries ‘But I loved her body too!’. Soon after, the dead Inger is resurrected bodily, apparently through the faith of her brother-in-law Johannes and that of her daughter. Inger’s spirit, her life, is returned to her corporeal body; it is in the minute flutterings of her fingers that we first perceive life returning to Inger’s corpse. This event fulfils, in a way, the hopes of the ancient Egyptians, mentioned in the first lines of Bazin’s ruminations on cinema’s defiance in the face of time and death. Ordet, like Michael, performs and flaunts this same cinematic defiance.

But Inger, and, with her, the Countess and Michael and the painter himself, are also embalmed in another way, in Ordrupgaard’s bringing together of Hammershøi’s still, quiet rooms and Dreyer’s moving images; and perhaps, also, in the digitized versions of some of Dreyer’s films available in this website. As Mulvey writes,[47] it is the ‘relentless movement’ and rhythm of cinema that robs it of the potential of the still images, of the photograph, to reveal its indexicality and therefore its direct, almost tactile, relationship to the dead one. And though this musealized sequence on a loop, or images from the streaming server, are not quite still images, they nevertheless, again in Mulvey’s words, ‘restore to the moving image the heavy presence of passing time and of mortality’ – and here I would add: of their reversal. The aura, she says, is returned to these ‘mechanically reproducible media through the compulsion to repeat’.[48]

Dreyer’s play with sculpture, then, speaks to what Dreyer shares with Bazin and with Barthes and indeed with the fundamental remit of the museum: the persistence and the mutability of matter. In this respect, the Thorvaldsen film can be seen as a lodestone for all Dreyer’s work. Just as Barthes writes of the photograph that the presence of the dead loved one ‘touches me like the delayed rays of a star’, Dreyer tries to re-activate in Thorvaldsen’s marble and plaster sculptures the sculptor’s fleshly desires and the dust and sweat of his work, in order to move the spectator – resurrecting the studio space in which flesh becomes stone and stone becomes flesh, creating dust of both.[49]

[1] . Andrei Tarkovsky: Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005: p64 Back

[2] Miss, Stig: ‘Foreword’ in Berner, Marie-Louise: Thorvaldsen: A Daguerrotype Portrait from 1840. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2005, p8 Back

[4] Fonsmark, Anne-Birgitte: ‘Forord’ in Hammershøi > Dreyer. Billedmagi. Copenhagen: Ordrupgaard Museum, 2006, p9. For a recent discussion in English of extant scholarship on other art forms in Dreyer’s films, see Harrison, Rebecca: ‘Haunted Screens and Spiritual Scenes: Film as a Medium in the Cinema of Carl Theodor Dreyer’ in Scandinavica 48:1, 2009, pp32-43 Back

[5] Fonsmark, Anne-Birgitte: ‘Forord’. In Hammershøi > Dreyer. Billedmagi. Copenhagen: Ordrupgaard Museum, 2006, pp9-10 Back

[6] I have since been advised by Casper Tybjerg that the films were exhibited in Barcelona quite separately from the paintings. Back

[7] Bordwell, David, The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981, p56. See also Tybjerg, Casper: ‘Det indres genspejling: Dreyers filmkunst og Hammershøis eksempel’ in Hammershøi > Dreyer. Billedmagi. Copenhagen: Ordrupgaard Museum, 2006, pp27-42 Back

[10] Mulvey, Laura: Death 24x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image. London: Reaktion Books, 2006, p181 Back

[11] Bazin, André: What is Cinema? Vol.1. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2005 (1967), p9 Back

[15] Barthes, Roland: Camera Lucida. Reflections on Photography. London: Verso, 1981, p80 Back

[18] Bordwell, David: The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981 Back

[22] Bogh, Mikkel (1997): Bertel Thorvaldsen. Dansk klassikerkunst. Copenhagen: Forlaget Palle Fogtdal, p32 Back

[23] Between 1750 and 1800, the practice of modelling in plaster emerged amongst sculptors in Europe as a solution to the prohibitive cost of working in marble or bronze. Paradoxically, however, the use of plaster by contemporary sculptors also placed their creations on a par with the classical works of art they were trying to emulate. The art historian Janson explains that ‘many of the surviving masterpieces of classical sculpture were themselves copies of lost originals, often with a change of materials (e.g., marble copies after bronzes), and because of their fame as embodiments of an aesthetic ideal these copies, in turn, were constantly reproduced as plaster casts for the benefit of students and connoisseurs.’ Janson, H.W.: Nineteenth-Century Sculpture. London: Thames & Hudson, 1985, p13 Back

[24] Allington, Edward: ‘Venus a Go Go, To Go’ in Hughes, Anthony and Erich Ranfft (eds): Sculpture and its Reproductions. London: Reaktion, 1997, p154 Back

[27] See Martensen-Larsen, Britta: ‘Om Carl Th. Dreyer’s Thorvaldsens kunst’. Konsthistorisk Tidsskrift LXIV, 2, 1995, pp117-28 Back

[30] ‘forstærkede den plastiske virkning’, Martensen-Larsen, p118 Back

[31] ‘de væsentlige detaljer af den menneskelige anatomi’, ibid. Back

[32] Henschen, Eva: ‘Lyset i Thorvaldsens Museum’ in Meddelelser fra Thorvaldsens Museum, 1998, pp55-67 Back

[33] See Sandberg, Mark: ‘Mastering the House: Performative Inhabitation in Carl Th. Dreyer’s The Parson’s Widow’ in Thomson, C. Claire (ed.): Northern Constellations: New Readings in Nordic Cinema. Norwich: Norvik Press, 2006, pp23-42 Back

[34] Marks, Laura U.: The Skin of the Film: , p129 Back

[37] Martensen-Larsen, p120 Back

[38] Licht, Fred: Sculpture: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. London: Michael Joseph, 1967, p34 Back

[40] Thorvaldsen ønskede bestemt ikke at hidse beskueren op og interesserede sig slet ikke for det svimlende blik og det bankende hjerte. Tværtimod, beskuelsesakten kunne ikke blive fredfyldt, kontemplativ og idyllisk nok […] Thorvaldsen ville […] gerne fuldstændigt undgå den begærlige relation til skulpturen. Nej, det mest nærliggende var faktisk at forestille sig skulpturen som alene med sig selv, helt hinsides ethvert samvær af nogen art. Bogh 1997, p31 Back

[42] ‘I dette Værk som i al Thorvaldsens Kunst er det Rytmen man glæder sig over. Han havde en egen Evne til at bygge Figurernes Bevægelser op til rytmiske […] Harmonier. Den rytmiske Musikalitet er den inderste geniale Evne hos Thorvaldsen. I sin klareste Form har han vist den i Relieffet med Priamus. Ansigternes Udtryk siger som sædvanlig ingenting – de må ikke drage Opmærksomheden bort fra den talende Rytme.’ Martensen-Larsen, p123 Back

[43] Martensen-Larsen, p125 Back

[44] Mulvey, p117

[45] ‘varmt levende Blod og ikke Fiskeblod’, Martensen-Larsen, p125 Back

[46] ‘…vil vi se, at der absolut ingen Elskovsfølelse er at spore i hendes Ansigt. Men så meget mere er der i Torsoen, der er fuldent, dejlig og bag Blufærdigheden ligefrem sitrer af indre Varme og Liv.’ Martensen-Larsen, p122 Back

[49] Parts of this article started life as papers for the conference ‘Film and the Museum’ at Stockholms Universitet in March 2007, and for the 2008 Hammershøi exhibition at the Royal Academy of Art in London. I would like to thank Thomas Elsaesser, Laura Mulvey, and Davina Quinlivan for commenting on these earlier papers. Much credit is also due to my Nordic Cinema students at UCL, especially Tiago De Luca, Hannah Gregory, Rebecca Harrison, Lauren Godfrey, Tom Haynes and Ian Meikle, whose class discussions and essays have opened up fruitful new ways of thinking about Dreyer. Back

BY CLAIRE THOMSON | 16. MAY