Whatever the conflicts that haunt the mind of a given period, I defy any spectator to whom such violent scenes will have transferred their blood, who will have felt in himself the transit of a superior action, who will have seen the extraordinary and essential movements of his thought illuminated in extraordinary deeds—the violence and blood having been placed at the service of the violence of the thought—I defy that spectator to give himself up, once outside the theater, to ideas of war, riot, and blatant murder.

-Antonin Artaud[1]

The source of the austere, recurring depictions of suffering in Carl Th. Dreyer’s films has been a point of interest and contention in scholarship that usually portrays him as an intense but always polite artist for whom filmmaking was his “only great passion”.[2] On several occasions, critics have gone so far as to characterize him as taking sadistic pleasure in tormenting his collaborators. Thefact that Maria Falconetti experienced a mental breakdown after filming The Passion of Joan of Arc (La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, 1928) likely sparked many of the rumors about Dreyer’s torturous filmmaking practices—rumors that he repeatedly took great pains to dispel.[3] In 1954, for example, during the filming of The Word (Ordet, 1955), Dreyer sent a short letter to the Danish newspaper, Information. “I am no Sadist” (Jeg er ikke sadist) as it was titled, opens with the following paragraph:

Numerous already are the myths about the means I employ, as a director, to get the actors participating in my films to perform as I wish. Torture, torment, and other physical and psychological abuse have been named. - Actors are pricked with needles, jabbed with knives, pinched with tongs, exposed to the effects of psychological shock of the most gruesome and outrageous sort, causing them to leave the studios at night, physical and psychological wrecks.[4]

Rhetorically speaking, the emphatic, detailed enumeration of the many forms of torture that he did not use betrays a curious intimacy with (or perhaps an intimate curiosity about) these practices. One might say that the language of the letter packs a rather gratuitous punch particularly considering the innocuous article that had supposedly provoked him.[5] In all probability Dreyer was still perturbed by an article, “The Tyrannical Dane” written by Paul Moor and published in Theatre Arts Magazine a few years earlier in 1951 in which he represents Dreyer in no uncertain terms as both frivolously sadistic and without the least concern for his actresses. Considering the flippant tone of Moor’s article, it is easy to understand how it provoked Dreyer. In reference to the filming of Jeanne, for example, Moor writes, “Dreyer's company and crew in Paris regarded him as a combined master, crackpot, and lunatic.” The following passage amounts to a straightforward condemnation of Dreyer’s methods, (if not of his ultimate status as a master filmmaker).

Dreyer's major works have all been concerned with anguish and horror, and his methods of achieving these effects have caused some hard feelings among his actors. The commonest charge against Dreyer is that he is a sadist. He has been known to pinch an actor cruelly in order to get a desired expression of pain. When Maria Falconetti played ‘Joan’ for him, Dreyer ordered all her hair cut off; Falconetti pled, raged, and, finally, conceding, wept bitterly; Dreyer not only filmed her weeping, but there were among those present some who swear he derived an uncommon enjoyment from the spectacle. They say the same of his decision that a young actor in ‘Day of Wrath’ be shorn of his rich, flowing locks - to no apparent purpose, as far as the plot and period were concerned. To achieve the proper wildness in the eyes of Anna Svierkjaer (sic), who was burned as a witch in ‘Day of Wrath,’ Dreyer left her bound to a ladder for two and a half hours in a blazing summer sun before photographing her; after the scene, Dreyer untied her and was solicitousness itself, but the 66-year-old actress had difficulty standing or even sitting up for several hours afterward.[6]

Aesthetic ambition and the bullfight

In what follows I would like to look more closely at Dreyer’s reaction to these accusations of sadism by drawing from an unpublished article he wrote toward the end of his career titled “My Article on Bullfighting” (Min artikel om tyrefægtning).[7] The piece affords an intriguing glimpse into Dreyer’s aesthetic imagination and ambitions. In illuminating the bullfight as art, the article functions as a defense of the controversial practice. Dreyer casts it as an initially disquieting spectacle that combines elements of performance, suffering, and death in a unity of danger and beauty. This is not to assert that Dreyer’s understanding of suffering or art remains static throughout his career. Rather, the bullfighting article provides a conceptual framework through which to understand how Dreyer’s films (and his understanding of the process of making art) generated discussions of sadism at all. At the heart of the matter are weighty ethical questions about the attribution of volition and agency to art’s offer, a word that in Danish denotes both victim and sacrifice.

In conjunction with the bullfighting article, I will consider related instances in Dreyer’s work in which reality becomes performance, performance becomes reality, and people get hurt. Dreyer’s fascination with dangerous realism and the limits of performance persisted throughout his career. I will consider three different instances in Dreyer’s film and script-work in which women (or female characters) die by fire. I will also look at an article that Dreyer wrote in 1926 about his visit to the set of Abel Gance’s Napoléon (not long before he began filming Jeanne d’Arc), in which he recounts his experiences observing the elaborate direction of a battle scene in which men were injured both on and off screen. These varied examples highlight how Dreyer’s artistic process draws upon ideas of authenticity and theatrical performance that in some sense exceed the goal of filmic representation. In other words, a film is sometimes more than the sum of its filmed parts.[8]

Similarly, the events in the bullfighting ring are only part of the story. Dreyer’s article suggests that understanding the traditions behind the spectacle (including a reverence for the sacrifice and psychology of its participants) is imperative to appreciating the bullfight-as-art. Granting legitimacy to aesthetic suffering by referring to tradition, psychology and process, serves to elevate and explain events that initially appear simply cruel. Dreyer’s defense of his occasionally intense filmmaking practices from the accusation of sadism involves a similar rhetorical move. I read Dreyer’s efforts to convey the arduousness of the artistic process: the ordeal and risk of its coming into being (which the final film can only ever partially document) and the demanding but voluntary participation of his actresses as an attempt to dispel the claim of gratuitous cruelty. The bullfighting article suggests that the creation of art that speaks to some larger aspect of human experience is an endeavor worthy of the self-sacrifice by its collaborators. To accuse Dreyer of sadism does nothing to help understand his artistic process, but neither is it helpful to assert that he simply remained a modest gentleman who never did anything questionable in the name of making art. Just as the bullfight can leave one with a queasy feeling that ethical boundaries have been crossed, so can Dreyer’s filmmaking. Perhaps Dreyer’s irritation with the entire topic of sadism betrays his own discomfort with the idea that art at its most authentic must be capable of transcending the ethical boundaries of everyday life. It is precisely this ethical gray zone—in which pathos created for some higher purpose verges on gratuitous human cruelty—that he inhabited and interrogated throughout his career.[9]

Call it theatre

Dreyer appreciates bullfighting as an intensely violent, but at the same time also an aesthetically refined experience. He uses vocabulary gleaned from several fine arts to describe it, from painting to dance and particularly the theater.[10] He treats the three phases of a bullfight as three acts of a play. Dreyer’s conception of the theater is perhaps more aptly conveyed by the broader term performance, considering that the term as he uses it encompasses such widely divergent practices as gladiatorial spectacle, pagan sacrifice, and tragic theater. “In the forms that bullfighting has assumed today it has nothing at all to do with sport. It should be called a play instead—along the lines of the ‘circenses’ held by the Roman emperors to entertain the people.”[11] The prologue walks the inexperienced spectator through the process of buying a scalped ticket at a local café upon discovering that the ticket office at the arena has “sold out”. Act one commences with the mayor’s waving a white handkerchief after which the matador undertakes a long string of “veronicas”[12] and it ends with the picadors entering on horseback - all attempts to exhaust and demoralize the bull. Act two, a very brief one, details the work of the banderillos who must place sharp, barbed darts (banderillas) in the neck or shoulder of the bull. In the third and final act, mirroring the commencement of the first, the matador again bows to the mayor for permission to kill the animal and then perhaps also to some other dignitary in the audience to whom he wishes to dedicate his kill. At this point the matador is granted fifteen minutes to dispatch the bull or face ridicule and shame. The bullfighter faces the bull alone at this point, performing his art by using the heart-shaped, scarlet muleta to guide the bull’s horns and head down to the ground (something Dreyer describes as an extremely dangerous maneuver), after which he draws forth steal to defeat his foe. Here the play becomes a question of life and death, “now it will be settled which of the two, man or bull, shall leave the fight the victor.”[13]

Although Dreyer overlays the bullfight with the structure of Greek tragedy he relates less about tragedy per se (for example, whether the bull or the matador plays the tragic hero in this extended metaphor) and more about the perilous risks undertaken in the name of theatrical, aesthetic effect.[14] Dreyer brings home the serious and titillating consequences of this play; the prospect of death electrifies the audience watching the aesthetic choreography of bodies in this mortal display of courage. The aesthetic pleasure and pathos he describes elevates the killing of the bull from mundane sport to art of consequence. The effect the risk undertaken for art will not be lost on a spectator possessing a sense of courage and nobility.

It is in the ‘veronica’ that the matador displays not only his composure and cool-headedness but also his style, as he, in the rhythmical swaying of his body, grants the spectators aesthetic pleasure. The matador’s work with his cape is devoted to a unity of danger and beauty, which cannot avoid making an impression upon people with a sense of courage and nobility. […] now one can truly speak of a bullfighting-art. Style has stepped into the foreground and the killing of the bull, which had previously been the goal of the fight, has slipped into the background.[15]

Over and again, bullfighting exemplifies the way in which life and death (or serious mutilation and injury, if you will) go hand in hand with creating meaningful, worthwhile art. “While toying with death, which crouches on the bull’s sharp horns, he creates a work of art, for the consummate matador goes out of his way to ensure that all of his movements are graceful and that his posture displays dignity.”[16] Or again, when Dreyer describes the effect of this fatal performance as being akin to a looking upon a living painting, sculpture, or even watching the graceful movements of a dancer,

When using his cape and the muleta he keeps his feet close together. The movements he makes with his cape and the muleta, when they are successful, give the spectator the impression of a live drawing, a piece of living sculpture—or if you will: a ‘figure’ in a ballet dancer’s solo number, arranged to the tiniest detail.[17]

Regardless of whether one chooses to condemn or extol the bullfight as aesthetic experience, Dreyer’s article clearly propounds an aesthetics that pushes the envelope.

Humanism and the gender of suffering

The bullfighting citations above would seem to suggest that Dreyer found suffering for the sake of aesthetic pleasure relatively unproblematic. That assertion becomes more complicated when held up against other evidence that Dreyer held a deep respect for art’s potential to reflect larger questions about humanity and the human predicament. Creating realistic, moving depictions of suffering remained central to Dreyer’s longstanding interest in humanism. Most of Dreyer’s projects engage not only with suffering per se but with some aspect of the causes of human suffering whether psychological, metaphorical, spiritual or the result of social prejudice or intolerance. We see suffering on account of a lover’s betrayal, or resulting from religious persecution, or coinciding with tough choices in the face of societal pressures.

It is certainly not irrelevant that Dreyer spent so many years of his life trying to create a film about the life of Jesus. In an unidentified interview from around 1965, an interviewer asked Dreyer whether his most recent film Gertrud (1964) wasn’t the most recent example of a theme that had concerned him throughout his life, namely the place of woman and the place of

love in woman’s life. Dreyer responded modestly, in English, that while this may not have been intentional, he had “always been attracted to people’s sufferings (sic) and particularly woman’s suffering.”[18] On one hand, Dreyer’s attraction to women’s suffering in particular would seem to indicate that he was nothing more than a man of his time, shuffling predictably amid sexist representations of women—the kind in which women are most beautiful (and aesthetically useful) when they are either suffering or dead.[19] On the other hand, the diversity of Dreyer’s suffering figures from Jesus, to Michaël’s Zoret, to the bull (who cannot be otherwise than male) would suggest that Dreyer viewed female suffering as particularly noble; or as unfortunately more common and therefore worth drawing attention to; or simply as one of many legitimate manifestations of the universal experience of suffering.

Meticulously composed death and suffering on set

The elegant figur of the bullfight mentioned above was hardly Dreyer’s first encounter with suffering incurred in the name of aesthetic creation. Whether or not Dreyer ever actually attended a bullfight, he did experience the perils of the realist film first-hand while researching his article entitled, “French film”[20]which brought him to the set of Abel Gance’s epic film Napoléon (1927), France’s largest and most elaborate film production to date. Gance, whom Dreyer refers to as Napoleon-like, had recently been injured in an on-set explosion during one of the film’s elaborately choreographed battle scenes. Dreyer observed three different takes including one immense battle scene involving between five hundred and eight hundred extras. The third scene that Dreyer describes amounts to a spectacle in and of itself. Wind and rain machines cause horses to rear while an army of extras receives its orders from an army of director’s assistants. Dreyer is particularly moved and impressed by the carnage of an enormous battle-scene in which the set is covered with actors and horses playing “dead”.

For the third shooting, the scenery was changed. A hill was to be stormed and taken. ‘Dead’ soldiers and ‘dead’ horses are covering the battlefield where the fight is to take place. Just as in the second shooting, Gance turns up with an arrangement so carefully planned that the ‘battle’ can be filmed without rehearsal.[21]

One can imagine Dreyer’s stylistic use of quotation marks as signaling a not-unexpected curiosity with death as a limit for ethically responsible film. (It is generally not acceptable for actors to perish in the creation of [fiction] film. The snuff film presents itself as a despicable exception.) This rhetorical gesture sets the stage, so to speak, for the “scene” that he will witness as he leaves, namely an infirmary full of actors who have actually been injured during production.

When I, confused and shaken, leave the studio, I see the ‘wounded’ gathered in the front room. The ‘warriors’ have been carried away by the heat of battle to such an extent that they have received long slashes, scratches, and deep wounds. Blood is flowing. Two nurses go around dressing wounds, in one of the director’s rooms a physician receives those most seriously injured. Gance himself probably doesn’t give them a thought.[22]

Dreyer’s shock at seeing the “wounded” is adulterated by an undeniable admiration for the individual sacrifice of these extras who, caught up in the heat of “battle,” incur deep wounds for their director and general. But the gravity of the gory scene is not lost on Dreyer who is reminded of a line he read on an advertisement for D.W. Griffith’s epic masterpiece Intolerance (1916) which included (among its various self-promotions about the extravagant number of extras and meters of film used) the unexpected claim that “During the shooting no human life has been wasted.”[23] (Emphasis in the original Danish.) Only after witnessing Gance’s hospital scene does Dreyer fully understand the import of the Intolerance boast. Obviously “French Film” is far from advocating the intentional sacrifice of actors for a film—Gance’s lack of concern for his injured actors appears cruel and heartless to Dreyer. Rather, the account seems intent on making an unappreciative spectator aware of the real costs of creating a cinematic masterpiece. Film is serious art. Considering that arteries are expressly punctured in the filming of Jeanne only a few years later, however, perhaps the experience convinced Dreyer that Gance’s elaborate film project was, when all was said and done, worth the real blood spilled to make it.

Performance on set

Along with the curious ambiguity of represented harm and real harm that Dreyer observes on Gance’s set (and to which I will presently return), something about the immensity of the production affects him profoundly. As Dreyer relates it, his nerves are made ragged by the performance of filming, well before he sees any actually wounded extras. “French Film” also hints at an underlying desire to convey the extraordinary coordination of technology and human effort behind the production, as if this might offset, to some extent, the injuries incurred in its process. The fact that extras were actually there, on set and injured in the process of filming proves that one hasn’t cheated in achieving the effect of realism. This in turn contributes something to the authenticity of the project. The authenticity that Dreyer hesitantly admires about the Napoléon production goes hand in hand with the curious ontology of the performance he observes. The realistic effect of the film derives from filming a performance event that happens a single time, not unlike the bullfight.

Just like other artists, the matador works constantly to improve his ‘style’ – to make his movements as aesthetically graceful as possible. In that way his work becomes art, which, just as that of the ballet dancer, is created before our eyes and which, when ‘the number’ is over lives only in the memory of those who have watched him. The great matadors, whose names are uttered with reverence, are in their own field geniuses like Diaghileff, Nijinsky og José Greco.[24]

Dreyer’s discussion of the bullfight as a fleeting art that comes about in the interaction between spectator and performer that then lives on only in memory illustrates an understanding of performance astute and expansive enough to include the performance event of a film set. It also suggests a role for film namely, to remember, as it were, some part of what it has seen. In Napoléon, this means documenting a battle too costly or elaborate to repeat. The immense amount of preparation needed to insure the success of the shot may or may not come across in viewing the film itself.[25] Dreyer scholarship often focuses on the formal composition and editing of his films as the sole concern of his filmmaking practice. I am suggesting that perhaps Dreyer’s “only great passion” incorporates an understanding of film as a more expansive performance experience. Dreyer’s appreciation of the film-set spectacle suggests that it is more than just means to represent a fictional world (a film, in other words). For Dreyer, a film’s authenticity relies upon more than what happens in front of the camera—process matters.[26] That Gance’s battle scene exists simultaneously as a unique performative event in its own right and as the culmination of the preparation that made it possible contributes to its authenticity. The bullfight exhibits something of the same temporality: simultaneously a single, unique performance and part of the age-old traditions that imbue it with larger meaning. A bullfight both represents larger (archetypal struggles), at the same time that it is nothing other than that struggle. There is no better or worse representation of a bullfight, for each performance of a bullfight is a bullfight. Dreyer’s filmmaking involves pressing upon this same, almost paradoxical position. Naturally, the goal of a film set is to create a filmic representation of a fictional world (the film). But for Dreyer, the resulting film exists as evidence of a much larger process (a world) of aesthetic creation.

Dangerous depictions and women in fire

Alongside any reflective appreciation of the bullfight that Dreyer might seek to convey is an account of the primordial passions that it can inspire (even in a Nordic audience inclined to prejudge Spanish and Mexican bullfighting as barbaric for all involved). The introductory passage reads as follows,

It is, on the other hand, a well-known fact that people who, despite their preconceived antipathy nevertheless decide to attend a bullfight – when they actually get there – find themselves to their own surprise carried along by the exhilaration of the fight and captured by the crowd’s hysterical excitement. Perhaps they experience – unconscious even to themselves – the intense sensation of witnessing an act originating in the long-since vanished sacrificial practices of pagan times.[27]

In comparing the bullfight to an age-old rite Dreyer emphasizes a reality rather than a realistic effect. This performance does not represent something else—the hysterical mass of spectators reacts to a real handling (event) rather than its representation. (The Danish word handling conveniently encompasses several ontological levels at once. It means action, deed and act as well as the representations of these, in plot, story, and also ceremony which falls somewhere in between.) Taking, for a moment, the same liberties that Dreyer does to generalize about the spectator’s experience, one might argue that the often immensely visceral representations of (sacrificial) suffering that recur in Dreyer’s films press upon the same ontological ambiguities between reality and representation to produce a similar effect.

Looking at Dreyer’s films themselves does little to help his argument that no real harm occurred on set; his depictions of physical and psychological abuse (suffering) demonstrate a realist aesthetic at its most extreme. Whether or not Dreyer’s actresses actually avoid being subjected to physical and psychological torture on set, many characters in his films are not so fortunate. Depictions of “torture, torment, and other physical and psychological abuse,” are some of the most compelling moments in Dreyer’s oeuvre, not in the least because they are so spectacularly realistic. Here again, he blurs the distinction between representation and reality in the pursuit of authenticity. Authenticity remains a critical aspiration for Dreyer, who spent innumerable hours researching the real people, real locations, real props and real historical sources he used in creating fictional films. That “real” suffering might have been an intriguing—if also a somewhat unsettling—fascination for him is not entirely surprising. Remainingan astute theorist of dramatic effect throughout his life, Dreyer frequently employed an effect common to avant garde theater, performance art, and spectacular stage melodrama, in which pathetic energy is created from watching suffering so vivid and “real” that a spectator’s concern for the well-being of a character is intertwined with (or even displaced by) a concern for the physical well-being of the performer’s body.[28]

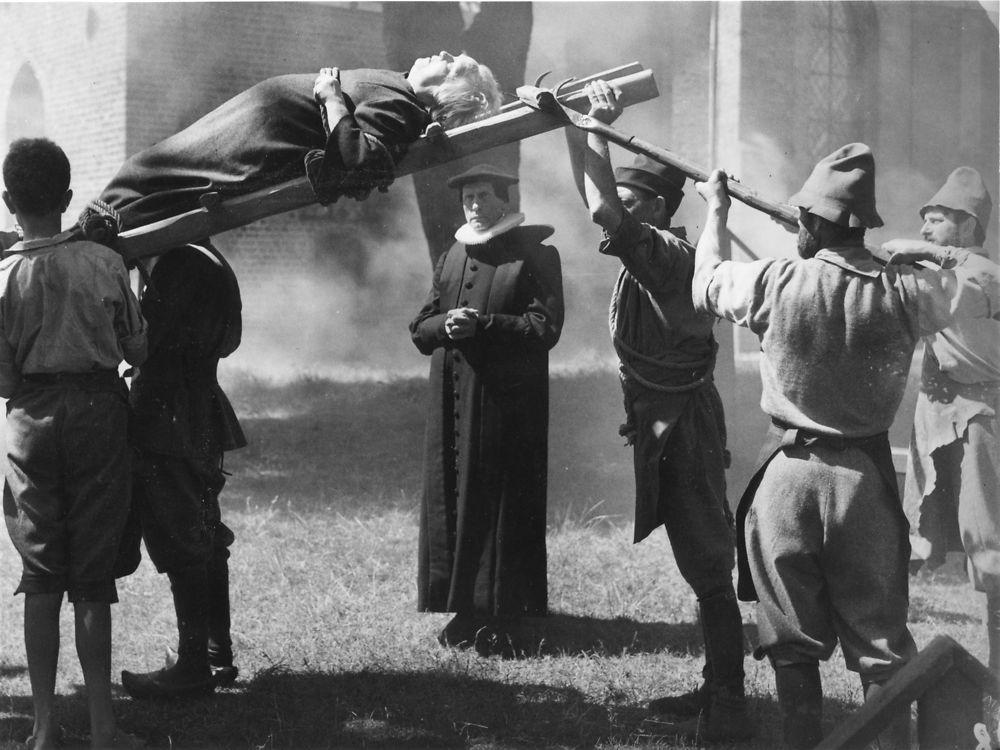

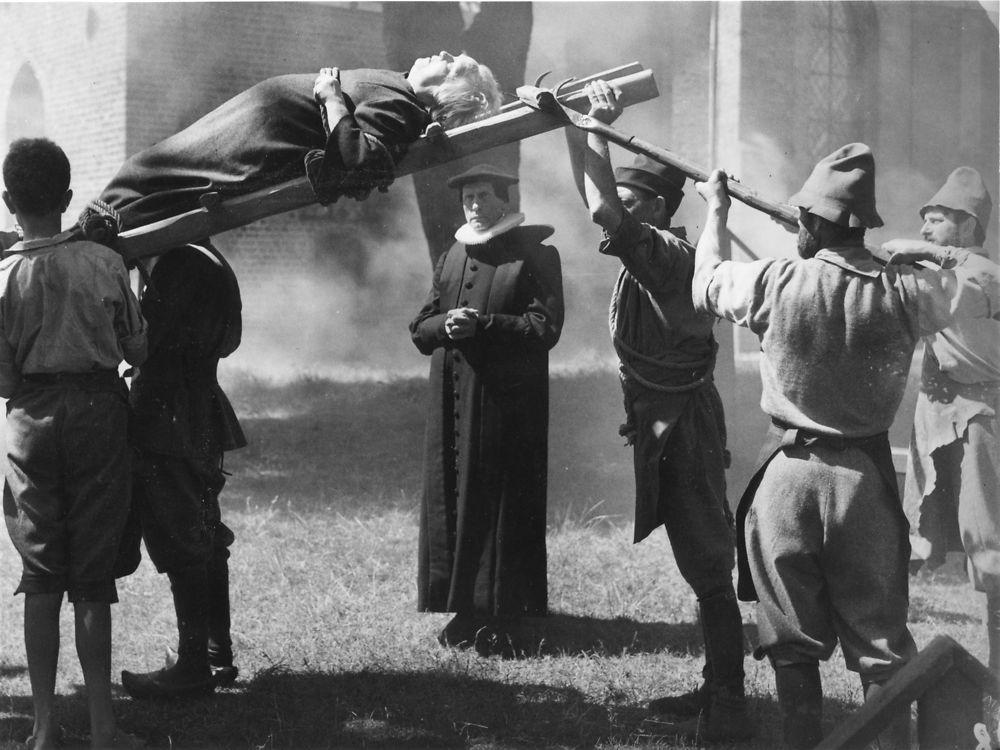

Dreyer uses this technique in Day of Wrath, for example, in the torturous scenes in which a long row of conspicuously male churchmen watch as their cohort exacts Herlofs Marthe’s confession. Our compassion for Herlofs Marthe derives from the realization that we too are among the fully clothed, heinously placid actor-persecutors watching the contortions of Anna Svierkier’s exposed body. Sverkier’s arms are pulled stiffly up behind her in a way that appears to cause pain in the older actress as well as to the character she plays. In another scene, after kneeling at the feet of Mester Absalon to beg for her life, Herlofs Marthe’s fragility becomes apparent when she falters as she attempts to stand. The elegant pathos of this scene arises out of the fact that nobody helps this determined but unsteady woman up to her feet again. Neither Absalon (nor Dreyer for that matter) comes to her aid. The same is true when she is tied to a ladder and burned alive.[29]

While the vacillation between the body of the actor and the body of the character is always a fundamental element of theatrical performance and mimesis, it becomes especially potent when the body in question incurs harm or death. In La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), our identification with the character of Jeanne is both shaken and reinforced when we are forced to consider whether the blood spurting out of “her” arm belongs to Falconetti or not. (Our concern for this arm—whether it belonged to a body double or not—is further complicated by a closer look at various versions of Jeanne, which reveals that the shots of the bleeding arm (s) do not match up entirely; Dreyer must have ordered at least two different punctures to achieve the vigorous bloodletting he desired.[30]) Watching Jeanne as she is about to burn at the stake, we forget to think about whether her subtle cough might have been scripted and instead sense the actress’s body actually deprived of air amid the smoke billowing around her. Scenes such as these are compelling because they cause concern for the bodily wellbeing of Falconetti herself. In these moments, the film’s fictional world blurs with the performative world on set to produce something of a documentary effect. Falconetti does not just play the role of a young girl whose head is shaved; her head is actually shaved. The actuality of the event leaves the spectator feeling that the fictional account she agreed to watch is tinged with the documentation of real human discomfort.[31]

Even in Dreyer’s very early career one finds curious instances of the perilous and thrilling conflation of performance and reality. Lydia, an early script that he wrote at Nordisk Films Kompagni (and that Holger-Madsen consequently directed in 1918) culminates in a climactic scene in which the eponymous heroine, a world-renowned dancer, commits suicide during the premiere performance of a death-defying “fire dance” [Ilddans]. This is perhaps the earliest instance of Dreyer’s interest in female characters that, like Herlofs Marthe and Jeanne, perish by fire. Lydia’s performance on stage begins as a performance, but then becomes real (albeit still within the fictional world of the film) when Lydia actually throws herself onto the “real,” on-stage fire that will eventually kill her. Even if the motivation for Lydia’s “choice” is a fierce societal condemnation of her illegitimate pregnancy, the theatricality of her leap seems intuitively to situate it in a different magnitude of choice than the representations of persecution and torture in Jeanne and Day of Wrath. Nevertheless, Lydia’s performance of a ritualistic sacrifice [described in the film’s program as “an adoration of fire” (en Tilbedelse af Ilden)[32]] and Dreyer’s favorable comparison of the bullfight to a sacrificial rite, while certainly to some extent coincidental, signals a productive and persistent ambiguity in the term offer.

These scenarios of burning each raise important ethical questions for Dreyer, about the attribution of agency and the productive but perilous ambiguity between victimization and beautiful sacrifice.[33] These issues bear a striking resemblance to those that occupy Dreyer in the bullfighting article - controversies that still surround the institution of bullfighting today. A first step in parsing out these issues in the context of Dreyer’s article will be to take a closer look at the roles of bullfighter and bull.

The honourable matador

Dreyer’s project of presenting the bullfight as a dangerous but worthwhile art revolves around establishing it as the collaboration of equal participants, each of whom undertakes psychological and physical risk. Like the ambiguity of the offer, neither bullfighter nor bull embodies either pure persecution or pure victimization. Dreyer illustrates how bullfighters suffer from constantly having to put their bodies in harm’s way. During the season, they undergo immense pressure and often carry out their profession (and face death) while sleep-deprived and exhausted. “Is it any wonder that his nerves fail him now and again?” Dreyer writes[34]. Bullfighters are often injured on the job and—of particular interest to Dreyer—they exhibit quite different psychological responses to the experience of being gored.[35]

The matadors’ nerves react quite differently after being gored. Many bullfighters are gored again and again without giving it a second thought. They display the same courage as before. Others lose their courage for a while, still others are permanently filled with fear and their names are quickly forgotten. When a bullfighter can no longer watch cool-headedly as a bull comes toward him, without having his nerves begin to tremble, he will soon be booed and jeered out of the arena. There is nothing more embarrassing than to see a bullfighter who has lost his courage and is now possessed by a cowardly fear.[36]

Acknowledging the bullfighter’s vulnerabilities shores up the claim that the bulls are not the only ones that risk life losing life and limb in the ring. But Dreyer also draws an important distinction between those bullfighters who engage and those who do not. While his sentiments on this matter might be intended as a critique of the unforgiving audiences in bullfighting countries who show no pity for cowardly matadors, it also suggests that Dreyer’s sympathy lies with the matador who dares (or chooses, which amount to the same thing in the context of the article) to engage. The implication is that truly professional bullfighters overcome their fears to face the implicit dangers of their profession. “The majority of matadors are courageous by nature, but all nevertheless feel fear creep over them immediately before the fight. But as soon as they stand face to face with the bull, fear couldn’t be farther from their minds. The courageous matador doesn’t fear the bull.”[37] Dreyer’s identification with the ordeal of the matador makes sense when read as the brave filmmaker, a consummate professional who, undeterred by the perpetual lack of funding and the constant pounding by faithless critics, overcomes his fears to step into the ring once again.[38]

The noble beast

The most artful bullfighting performance is nothing without a spectacular bull to complete it, however, and Dreyer’s psychology of the bull affords a moving portrait of its crucial contribution. The emotional heft of his article resides with the bulls that choose, against all odds, to fight. Some bulls may refuse to charge but Dreyer imbues those that do—the noble ones that devote themselves to the fight—with a doggedness and courage worthy of our admiration.

Just as one demands ‘honor’ of the matador one demands ‘nobility’ of the bull. It is not just the matadors whose names are mentioned with reverence. The bulls are also remembered. A book has been published about famous bulls, referred to by name, that details the most important information about their lives. In the ring, sympathy lies just as often on the bull’s side as on the matador’s, and the spectators shed genuine tears when an otherwise valiant bull must finally concede and give up the ghost.[39]

An appreciation of bull’s sacrifice is as important as an appreciation of the bullfighter’s mastery of technique. Its desire to attack despite its wounds and its likely demise can create as much pathos (i.e. genuine tears) as a matador’s brave or artful victory. When Dreyer mentions that a bull can opt not to charge (something akin to the actions of the matador-turned-coward), he quickly reinforces the bravery of the real bull that does by charging rhetorically three times in the text, in quick succession, in a single paragraph. The truly courageous fighting bull is not afraid of anyone or anything. The truly brave bull engages without hesitation and by its own fighting instinct, because it itself yearns for the fight, and it attacks time after time, tirelessly. The truly brave bull does not try to ‘frighten—it attacks with its tail raised.[40] [My emphasis.]

Fleeing is apparently not an alternative for Dreyer’s bull, but neither would it want to. To do so would be to act against its nature, to violate its own instinct(egen drift) and act, as it were, unprofessionally. Dreyer’s personification of the bull grants it an element of agency or self-determination from whence its nobility also derives. The truly brave bull creates pathos by being something other than a cruelly persecuted victim-object.[41] The bull’s “choice” to participate is clearly not a false choice for Dreyer. The bullfighting piece draws attention to the possibility that conflating a bull’s self-sacrifice with the simple victimization of an unwitting innocent is to inflict an equally demeaning violence upon the bull’s noble efforts. If Dreyer intends the bull’s predicament to reflect humanity’s then things appear bleak. However, Dreyer’s insistence upon the bull’s dedication to something greater, something by which it might transcend the limitations of its situation, remains provocatively redemptive. The underlying implication is that the production of art, in its aspiration to be something more than everyday life, is worth violating the ethical principles one otherwise chooses to live by.

Dreyer repeatedly insisted on a similar capacity for choice and self-determination in those who worked with him. He contended that the greatness of Maria Falconetti’s performance in Jeanne depends on her having acted of her volition. In one article, Dreyer is described as destroying the myth of Falconetti’s coersion by insisting that her tears on set were “of her own free will - from her own heart.”[42] Certainly, some of the hyperbole of “Jeg er ikke sadist” must be attributed to what Dreyer interpreted as a slight against his collaborators whose talents, efforts and sacrifices he admired and depended upon. If, as the accusation of sadism implies, the heartfelt emotion in Dreyer’s films were to emerge only from the objectifying victimization of his sadistic directorial practices, then it would follow that his actors would appear incapable of producing affect on their own. Dreyer must also have understood “sadism” as implying that his actors would not willingly sacrifice their physical or mental well-being to make art with him, for on several occasions he emphasizes that making a film with him may be demanding, but it is always voluntary. “A director cannot force an actor to do anything that the actor doesn’t have the strength for. It has to come from within and without compulsion.”[43] This statement resonates with his statements about the ideal bull. Just as the truly brave bull achieves its full potential in a glorious fight, the truly strong actor demonstrates the will to collaborate and thus attain his or her full professional and artistic potential.

Dreyer’s assessment of the bull’s performance (or by extension that of his collaborators) verges on paradoxical and ethically questionable when he undermines the clarity of the bull’s volition (and in effect, its nobility) by pointing out that it remains forcefully innocent of the rules of the fight. Because of its intelligence and capacity to learn, by law the bull must remain unknowing; it can never have experienced an arena before. By way of establishing the bull as a highly intelligent animal, Dreyer writes that with the least bit of experience, it will easily learn to disregard the cape and gore the matador instead.

The truth is, that if the bulls were permitted to train to the same extent as the bullfighters and were permitted to take part in fight after fight and thus gather experience they would, on account of their courage, wisdom and good memory, be invincible and kill all of the bullfighters who dared face them.[44]

Dreyer further compounds the ethical quandary that he (perhaps inadvertently) raises, by relying on the blurring of representation and reality for authentic effect. The bull participates in a spectacle (it performs, more or less) but it does not perform any role different from what it is. In the same way, Dreyer frequently cast non-actors, particularly in his early films. These “actors” are brought into the ring, so to speak, to “play” a role that is nothing different from what they actually are. Being and representing are again blurred in the name of realism and pathos in a way that causes ethical quandaries. Whereas a matador’s challenge is to fight what he knows might harm him, the bull doesn’t act nobly; it is the (intelligent but somehow unthinking) embodiment of nobility itself. The bull’s body is the role it plays in the spectacle. But at the same time, Dreyer needs bull’s nobility to rest on its willing choice to collaborate. It must choose to be more or less nobly. It would be overstating it to say that Dreyer preferred his actors and actresses to be like bulls, the elegant, noble combination of blind courage and innocent unknowing—to be on film rather than to act.[45] One need only look at Anne’s fatal quandary in Day of Wrath, however, to be reminded that willing remains a fascinating, but unresolved category for Dreyer. This lack of resolution makes Dreyer’s work compelling (and perhaps also disturbing, depending one’s view of art) in asking ethical questions both within and beyond the frame of the film.

To what end?

Regardless of Dreyer’s intentions for the bullfighting article, the document attests to his acute awareness of theatrical effect. It illuminates larger ideas about how he exploited ambiguity between performance and reality to create a rich, pathetic realism and it also gestures provocatively back to older traditions of religious ritual and theatrical spectacle. Further, “Min artikel om tyrefægtning” gives contour to an artistic project in which aesthetic authenticity is worth the risk of injury. The lengths to which Dreyer went to achieve certain ideals of authenticity—whether in causing his collaborators discomfort, forcing his actors to inhabit sets, or pushing his actors to the limits of their corporeal integrity—suggest that he approached film as a more expansive (and I argue, performative) process than as simply the means to produce compelling cinematic images. I am proposing, in other words, that more is at stake in Dreyer’s filmmaking practice than the creation of the final cut. This makes sense if one posits a world, as Dreyer does, in which film is serious art that has the potential both to reflect quotidian human experience and also to transcend that experience. Seen from this perspective, Dreyer’s filmmaking quickly heads into deep philosophical waters. The pursuit of aesthetic creation or edification seems to justify Dreyer’s temporary suspension of certain ethical rules of behavior. If process, for Dreyer, must be at least as authentic as the images it brings about, then it is not surprising that ethical quandaries involving real suffering inevitably occur. When Dreyer scholarship focuses as it often does, on the masterfully luminous images and transcendent formal elements of his films, it loses sight of the way that Dreyer’s immersive logic of film performance enacts its own investigation of the intersections between ethics and aesthetics. The implication is that Dreyer did not view filmmaking as fundamentally different from the essential human experiences: loss and longing, intolerance, betrayal and suffering that otherwise preoccupied him.

Dreyer’s exploration of the ambiguity between victim and sacrifice (and particularly the ideas of free will and collaboration that he latches onto) might engender an ethical queasiness in a contemporary spectator, just like the bullfight. His sincere admiration for the bull’s character and sacrifice combined with his remarkable reluctance to cast the brave bull as the helpless victim of forces beyond its control (and to pity it for its unwitting persecution) provides the metaphor for his view of the collaborative artistic process. It cautions the viewer not to attribute simple notions of victimhood, whether to actresses contributing their full artistic potential to a difficult project, or to bulls fighting nobly and beautifully, against all odds.

Raising questions about the legitimacy and function of aesthetic suffering, however, is not to resolve them. The ethical risks of the realist film set (with its perilous combination of beauty and danger) clearly affected and unnerved Dreyer. The urgency with which he set about dispelling the rumors of sadism must certainly be understood in part as his own uncomfortable admission that using actual (even if consensual) suffering to create effective representations of it risks violating the larger humanist goal of alleviating suffering in the first place. Whether or not Dreyer took pleasure per se in the suffering of his collaborators, he lived to make art that treated not only life’s triumphs, but also the potential beauty in its cruelties.

[1] Artaud, Antonin. The Theater and its Double. Grove Press: New York, NY. 1958. p. 82. Translated from the French by Mary Caroline Richards. Interestingly, Artaud played the character of Massieu in Dreyer’s film La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928) and also Marat in Abel Gance’s Napoléon (1927), both of which will be discussed below. Back

[2] An excellent source for the standard reception of Dreyer as a reserved, serious, always-gentlemanly artist is “My Only Great Passion: The Life and Films of Carl Th. Dreyer” by Jean Drum & Dale D. Drum’s, Scarecrow Filmmakers Series No. 68: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham, Maryland, and London: 2000. Back

[3] One might even say that Dreyer deliberately incorporated this myth-busting into his artistic persona. Lars von Trier’s very public fascination with De Sade’s Justine during film school or of his tortured relationships with his actresses serves as less subtle variation on the practice of using Sadism to construct one’s artistic persona. Back

[4] “Carl Th. Dreyer: I am no Sadist” (“Carl Th. Dreyer: Jeg er ikke Sadist”) Information 28/7 1954. Unless already published in English, all translations from Danish to English are my own. [Mangfoldige er allerede de myter som beretter om, hvilke midler jeg som instruktør benytter mig af for at faa de skuespillere, der medvirker i mine film, til at spille, som jeg ønsker. Der nævnes tortur, pinsler og anden legemlig og sjælelig mishandling. – Skuespillerne prikkes med naale, stikkes med knive, knibes med tænger og udsættes for psykisk chockvirkning af den grusomste og mest oprørende art, saa de om aftenen forlader studierne som legemlige og psykiske vrag.] Back

[5] Most of that article (which had appeared in Information a few days earlier) addressed the adverse weather conditions that threatened the filming of Ordet. It ended with a brief anecdote about how an actor (who had played a role in Ordet at Betty Nansens teater years earlier) had approached Dreyer about a part in his film. To this Dreyer had supposedly remarked, “You were the worst of the entire cast!” [De var den ringeste i hele ensemblet!] At most, this comment shows that Dreyer could be brutally frank, but it is far from sadistic. It was not to potential actors that he addressed his response for as he also remarked, the great number of actors still willing to work with him proved that he was not a sadist. Dreyer wrote numerous set-the-record-straight letters to the editor throughout his career in defense of his public persona. Back

[6] “The Tyrannical Dane” by Paul Moor, from Theatre Arts Magazine, April 1951. This article is also available on line at: http://www.mastersofcinema.org/dreyer resources.htm Back

[7] Although the piece is undated, it makes reference to Hemingway’s Death in the Afternoon, published in 1932, and its placement in the archive suggests that it was written later in his career, probably while working as the director of Dagmar Theater, which he did from 1952 until his death in 1968. Dreyer’s manuscript was folded in an envelope encased, in turn, in another tattered envelope also labeled in Dreyer’s hand “Dagmar Teateret’s KRONIKKER” [Dagmar Theater’s Editorials]. I found the document in a bundle in one of the unregistered file cabinets in the Dreyer collection. It appears to be a fairly polished draft with few hand-written revisions, but what Dreyer actually intended to do with the piece, or why it was never published is unclear. Back

[8] An interview with Baard Ove about the filming of Gertrud provides anecdotal evidence for the importance of the unseen on set. Dreyer tries to impress upon the young actor that a tapestry hanging on a bedroom wall of the set was important to the film regardless whether it was ever “seen” by the camera. Considering the extensive research and collecting that Dreyer conducted for his film projects, I would argue that his immense textual apparatus (which occasionally makes its way into the frame of the film—such as in the opening sequence of Jeanne in which we see the actual trial document) should also be considered an integral part of Dreyer’s process—one that also in some sense exceeds the goal of filmic representation. Mark Sandberg has written on Dreyer’s elaborate, painstaking and sometimes architecturally cumbersome attempts to create authenticity on set. See "Mastering the House: Performative Inhabitation in Carl Th. Dreyer's The Parson's Widow." In C. Claire Thompson, ed. Northern Constellations: New Readings in Nordic Cinema. Norwich: Norvik Press, 2006. Back

[9] One finds traces of Dreyer’s interest in ethical and moral questions in the Dreyer collection housed at the Danish Film Institute. Among the hundreds of newspaper clippings that he saved on a wide variety of subjects, is one bundle that he labeled “ARKIV: Etik og Moral” [ARCHIVE: Ethics and Morality] which contains articles from the 1930s and 40s about topics ranging from “Dødsstraffen,” [The Death Penalty] “Hjemløse,” [Homelessness] and “Forbryderpsykologi” [Criminal Psychology] to “Ægteskab,”[Marriage] “Børneopdragelse,” [Child rearing] and “Kvindeproblemer” [Women’s Problems]. (These are Dreyer’s subheadings.) This “archive” also includes extensive notes he wrote while reading contemporary works on ethics and morality. Back

[10] Although the article does not overtly address cinema it does make reference to the composition of the image: “Efter en lang række ‘veronicas’ kommer der nu mere liv i billedet…” [After a long series of ‘veronicas’ more liveliness comes in the picture.] (Dreyer, Min artikel om tyrefægtning p. 4.), suggesting either an attribution of filmic vocabulary to the spectacle, or a pictorial conception of the bullfighting “stage”—a conception of theater that makes sense considering the pictorial compositions in Dreyer’s films. “Billedet” can mean: image, pictures, portrait, shot, painting, and photograph. Back

[11] Dreyer, Carl. Min artikel p. 1. [Under de former tyrefægtning idag har antaget har den intet med sport at gøre. Snarere maa den kaldes et skuespil – i lighed med de ‘circenses’ de romerske kejsere lod opføre for at forlyste folket.] Unpublished manuscript housed at the Danish Film Institute’s Dreyer Collection hereafter referred to as: Min artikel. (The page numbers are Dreyer’s.) Back

[12] A veronica is a common “lance” or pass made by the bullfighter. The move is named after Saint Veronica who is said to have wiped Jesus’ brow as he walked to Golgotha. Back

[13] Dreyer, Min artikel p. 6. [nu skal det afgøres hvem af de to, mand eller tyr, der skal gaa ud af kampen som sejrherre.] Back

[14] One of the few hand-written markings on the manuscript is the following line, carefully crossed out with red pen. It reads, “The bullfight can take the shape of a tragedy for the man – for the bull’s it always does.” (Tyrekampen kanforme sig som en tragedie for manden – for tyren er den det altid.) Back

[15] Dreyer, Min artikel p. 4. [Det er i ‘veronica’en at matadoren viser ikke blot sin ro og koldblodighed men ogsaa sin stil, idet han ved sit legemes rytmiske bøjninger skænker tilskuerne en æstetisk nydelse. Matadorens arbejde med kappen gaar op i en enhed af fare og skønhed, der ikke kan undgaa at gøre indtryk paa mennesker med sans for mod og adel. […] man nu virkelig kan tale om en tyrefægter-kunst. Stilen er traadt i forgrunden og drabet af tyren, som tidligere var kampens maal, er gledet i baggrunden.] The term koldblodighedcould be translated as cool-headedness but also as cold-bloodedness or heartlessness. Back

[16] Dreyer, Min artikel p. 7. [Mens han leger med døden, der sidder paa lur i tyrens spidse horn, skaber han et kunstværk, for den fuldendte matador gør sig umage for, at alle hans bevægelser er yndefulde og at hans holdning viser værdighed.] Back

[17] Dreyer, Min artikel p. 7. [Naar han bruger kappen og muleta’en, holder han sine fødder tæt sammen. Bevægelserne han gør med kappe og muleta’en giver, naar de er vellykkede, tilskueren indtryk af en levende tegning, et stykke levende skulptur – eller om man vil: af en i de mindste enkeltheder gennemarbejdet ‘figur’ i en balletdanser’s solonummer.] Back

[18] This interview is available on-line at: http://www.mastersofcinema.org/dreyer/resources.htm Dreyer scholar Martin Drouzy reads Dreyer’s fascination with female figures as his way of dealing (perpetually) with the mother who gave him up for adoption and then died shortly afterward in an attempt to abort her second child. Back

[19] See Bronfen, Elisabeth. Over her dead body: Death, femininity and the aesthetic. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992. Back

[20] “Fransk film” was originally published in Politikens magasinet January 5, 1926 and reprinted in: Dreyer, Carl Th. Om filmen: Artikler og Interviews. Ed. Erik Ulrichsen. Gylendals Uglebøger. 1964. Back

[21] The English translation of all quotes in “French Film” are from Skoller, Donald ed. Dreyer in Double Reflection: Carl Dreyer’s Writings on Film. Da Capo Press: New York, NY. 1973. (p.45) [Til den tredje optagelse var landskabet blevet ændret. En høj skulle stormes og indtages. ‘Døde’ soldater og ‘døde’ heste dækker valpladsen, hvor slaget skal stå. Ligesom ved den anden optagelse møder Gance frem med et så omhyggeligt udarbejdet arrangement, at ‘slaget’ kan optages uden prøve.] Dreyer, “Fransk film” in Om Filmen s. 29. Back

[22] Skoller. Dreyer in Double Reflection. p. 45. The visceral reaction that Dreyer reports is reminiscent of the reaction he describes in the bullfight’s hysterically invigorated spectator. [Da jeg fortumlet, med oprevne nerver forlader atelier’et, ser jeg i forstuen de ‘sårede’ forsamlet. I den grad er krigerne blevet påvirket af kampens hede, at de har hentet sig lange flænger, rifter og dybe sår. Blodet flyder. To sygeplejersker går rundt og anlægger forbindinger, i et af direktørernes værelser modtager en læge de værst medtagne. Gance selv skænker dem formodentlig ikke en tanke.] Dreyer Om Filmen s. 30. Back

[23] Skoller. Dreyer in Double Reflection. p. 46. “Under optagelserne er intet menneskeliv gået til spilde.” Dreyer Om Filmen p. 30. Back

[24] Dreyer, Min artikel p. 7. [Som andre kunstnere arbejder matadoren bestandig paa at forbedre sin ‘stil’ – paa at gøre sine bevægelser saa æstetisk yndefulde som muligt. Derved bliver hans arbejde en kunst, der ligesom balletdanserens skabes for vore øjne og som naar ‘numret’ er forbi kun lever i erindringen hos dem, som har set ham. De store matadorer, hvis navne nævnes med ærefrygt er paa deres felt genier som Diaghileff, Nijinsky og José Greco.] Back

[25] Dreyer often demanded that his actors repeat a scene numerous times until it was to his liking. My reading of Dreyer’s experience on Gance’s set in terms of an experience of immediacy refers to the scenes interspersed with such meticulous repetition, scenes like the shaving of Falconetti’s head in Jeanne d’Arc, which could not be filmed more than once without cheating, i.e. without violating Dreyer’s standards of authenticity. Back

[26] Consider Dreyer’s economically questionable decisions to film Jeanne in sequence coinciding with the chronology of the film’s trial and to keep all of the actors on set everyday regardless of whether they were to perform in front of the camera that day or not. Clearly Dreyer is interested in the impact a performance event that exceeds what is immediately visible in the frame of the film. Back

[27] Dreyer, Min artikel p. 1 [Det er dog paa den anden side en kendsgerning, at mennesker, der trods forudfattet antipati dog bestemmer sig til at overvære en tyrefægtning – naar de først er der – til deres egen overraskelse rives med af kampens spænding og indfanges af tilskuermængdens hysteriske ophidselse. Maaske har de – sig selv ubevidst – en intens fornemmelse af, at de overværer en handling, der har sin oprindelse i længst forsvundne hedenske tiders offerskikke.] Back

[28] For a discussion of the way that spectacular stage melodrama put its heroines in the way of “real props” like timber saws and locomotives, see Ben Singer, Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and its Contexts. Columbia UP. Columbia, NY. 2001. Performance theorist Erica Fischer-Lichte offers a different take on a similar performance effect, one she calls “perceptual multistablity”. For Fischer-Licthe the effect derives from a vacillation in perception that occurs at a phenomenological level during a performance event. At moments of potential harm, the audience ceases to reflect on the performance as performance and instead just perceives—amounting to a kind of extreme identification with the performers. Interestingly, in Singer, this vacillation or multistability entails a certain reflective break with fictional illusion. (This goes against typical assumptions about audience identification with melodramatic characters and plot.) Fischer-Lichte’s book, The Transformative Power of Performance: A new aesthetics Routledge Press London and New York, 2008 and translated by Saskya Iris Jain offers an excellent discussion of avant-garde performance technique, including its roots in circus sideshow performance and religious ritual. Back

[29] Drum and Drum includes a production still of Anna Sverkier during the filming of Day of Wrath. The caption reads, “Day of Wrath, Anna Svierkier on the ladder with aching back and an expression of real agony (picture from A/S Palladium)” [Drum and Drum photo insert between p. 173-174] (my emphasis) Back

[30] Thank you to Mark Sandberg for bringing this detail to my attention. Back

[31] Benjamin Christensen’s film Häxan (Witchcraft Through The Ages, 1922), a film that Dreyer openly admired for its artistic and technological potential (at least in its conceptual stages [see Dreyer’s article “Nye ideer om filmen. Benjamin Christensen og hans ideer.” Politiken. 1.1.1922. Also included in Om filmen.]) becomes an interesting precursor film dealing with questions of performance and torture. In one episode, Christensen films one of his actresses (acting only as an actress, not a character) with her thumb in thumbscrews—this purportedly to illustrate the kind of torture techniques to which accused witches were subjected. The re-release of this film in 1968 with narration by William S. Burroughs suggests interesting conceptual parallels between Scandinavian silent cinema and the performative turn in avant-garde art in the 1960s. Back

[32] Although Holger-Madsen’s film Lydia no longer exists its program, script and production stills are extant. A great number of these early Danish cinema programs have been digitalized by the Danish Film Institute and are accessible through the Danish National Filmography. One of the production stills includes what must be Lydia with her “fire worshipers” performing the Fire Dance. Back

[33] I read Dreyer’s engagement with the offer concept (victim and sacrifice) as developing out of his early experiences at Nordisk. Whereas one might assume that the moral position of the victim in Nordisk’s early films would be easy to predict considering that they are often referred to as melodrama and melodrama as a narrative mode frequently situates its moral universe around the figure of an innocent woman ruthlessly persecuted. In actuality, the complexity with which Nordisk offer films revel in this ambiguity is often underestimated. Lydia’s film program advertises the film as a tragedy. Both the program and Dreyer’s script imply that Fribert, the man who (being desperately in love with Lydia) tries in vain to save her from the fire, goes immediately mad, and throws himself off the theater roof—is the actual offer in this scenario. Fribert both sacrifices everything and becomes a victim of love. Back

[34] Dreyer, Min artikel p. 7. [Er det noget under, at hans nerver undertiden svigter?] Back

[35] Anecdotally, many modern bullfighting rings (like Gance’s set) house their own on-site infirmaries in the event of injuries. Back

[36] Dreyer, Min artikel p. 4. [Matadorernes nerver reagerer meget forskelligt efter en stangning. Mange tyrefægtere bliver stanget gang efter gang uden at de bagefter skænker det en tanke. De viser det samme mod som før. Andre mister modet for en tid, atter andre faar frygten i sig for bestandig, og deres navne glemmes hurtigt. Naar en tyrefægter ikke længere koldblodigt kan se tyren komme imod sig, uden at hans nerver begynder at dirre, vil han snart blive hujet og pebet ud af arena’en. Der er intet pinligere end at se en tyrefægter der har mistet sit mod og nu er besat af en kujonagtig frygt.] Back

[37] Dreyer, Min artikel p. 7. [Flertallet af matadorer er af naturen modige, og dog føler de allesammen umiddelbart før kampen frygten krybe over sig. Men saasnart de staar overfor tyren, tænker de overhovedet ikke paa faren. Den modige matadoren frygter ikke tyren.] Back

[38]Also offsetting the accusations of sadism in the context of Dreyer’s oeuvre is the way in which his auteur persona frequently rests upon playing the role of the persecuted artist who boldly endures all forms of criticism, misrepresentation and ridicule in the relentless pursuit of his artistic vision. Back

[39] Dreyer, Min artikel p. 8. [Som man kræver ‘ære’ af matadoren kræver man ‘adel’ af tyren. Det er ikke blot matadorerne, hvis navne nævnes med ærefrygt. Ogsaa tyrene huskes. Der er udkommet en bog om berømte tyre, nævnt ved navn og med angivelse af de vigtigste data i deres liv. I arenaen er sympatien lige så ofte paa tyrens side som paa matadorens, og tilskuerne fælder oprigtige taarer, naar en ellers tapper tyr tilsidst maa give op og bide i græsset.] Back

[40] Dreyer, Min artikel p. 8. [Den virkelig modige kamptyre er ikke bang for nogensomhelst eller nogetsomhelst. Den virkelig tapre tyr inlader sig uden tøven og af egen drift i kamp, fordi den selv ønsker kamp, og den angriber gang efter gang, utrætteligt. Den virkelig tapre tyr forsøger ikke at ‘skræmme’, men angriber med løftet hale.] Back

[41] Much of Dreyer’s work deals with volition and free will both at the level of the characters in his films and also at the level of their production. The plot of Day of Wrath revolves explicitly around the status of Anne’s will. Gertrud Kanning, the eponymous main character in Gertrud (1964), also muses on the matter of free will and determinism. In conducting research for Gertrud Dreyer became interested in Maria von Platen (the inspiration for Hjalmar Söderberg’s play that Dreyer adapted. Von Platen enjoyed an intimate relationship with Swedish literary scholar John Landquist (upon whom the Axel Nygren character is in part modeled) and supposedly helped Landquist write parts of Viljan : en psykologisk-etisk undersökning (Will: A Psychological-ethical investigation), published in 1908. Viljan is one of the many sources of which Dreyer read large parts. His extensive research notes exist in the Gertrud files of the Dreyer collection. Back

[42] “Admiration for Carl Th. Dreyer” (“Beundring for Carl Th. Dreyer”) Aktuelt December 20, 1965. The relevant passage reads, “Dreyer himself destroys that myth and relates that on the contrary he and his actress had worked the entire time in the perfect agreement, and everything that the girl had given came voluntarily—from her own heart.” [Dreyer afliver selv den myte og fortæller at han og hans skuespillerinde tværtimod hele tiden havde arbejdet i den bedste forståelse, og at alt hvad pigen havde givet var kommet frivilligt – fra hendes eget hjerte.] Back

[43]Ninka, 33 Portrætter (Copenhagen: Rhodos, 1969), cited in English, in Drum & Drum p. 131 Back

[44] Dreyer, Min artikel p. 8. [Sandheden er, at dersom tyrene fik lov at træne i samme omfang som tyrefægterne og fik lov at deltage i kamp efter kamp og indsamle erfaringer, vilde de paa grund af deres mod, klogskab og gode hukommelse, blive uovervindelige og dræbe alle de tyrefægtere, der vovede sig imod dem.] Back

[45] Despite Dreyer’s repeated assertions that many actresses and actors wanted to work with him (which they presumably wouldn’t have had he been a sadist) few of them actually did work with him more than once. Clara Weith [Pontoppidan], who appeared in Once upon a time (Der var engang, 1922) and Leaves out of the Book of Satan (Blade af Satans Bog, 1920) is one exception. Back

By Amanda Doxtater | 17. August