Mystery

I was twelve years old when my interest in Carl Th. Dreyer first arose. How did that come about? I wish I knew the answer. What was it that caught my interest back then, so many years ago now, as I was passing by a second-hand book shop in Elmegade in Nørrebro, idly letting my gaze roam the shop windows, but soon homing in on film researcher Martin Drouzy’s two-volume work: Carl Th. Dreyer, born Nilsson? Was it the picture of the aging Dreyer, seen in profile on the cover, that lured me into the shop and towards the book, which I immediately flipped through? I do not know. The book cost DKK 200, which I did not have, but my father had a solution. He said that if the imminent parent-teacher conference at my school went well, I would get the book as a form of reward. Some higher power was with me that particular year, and the book was mine.1

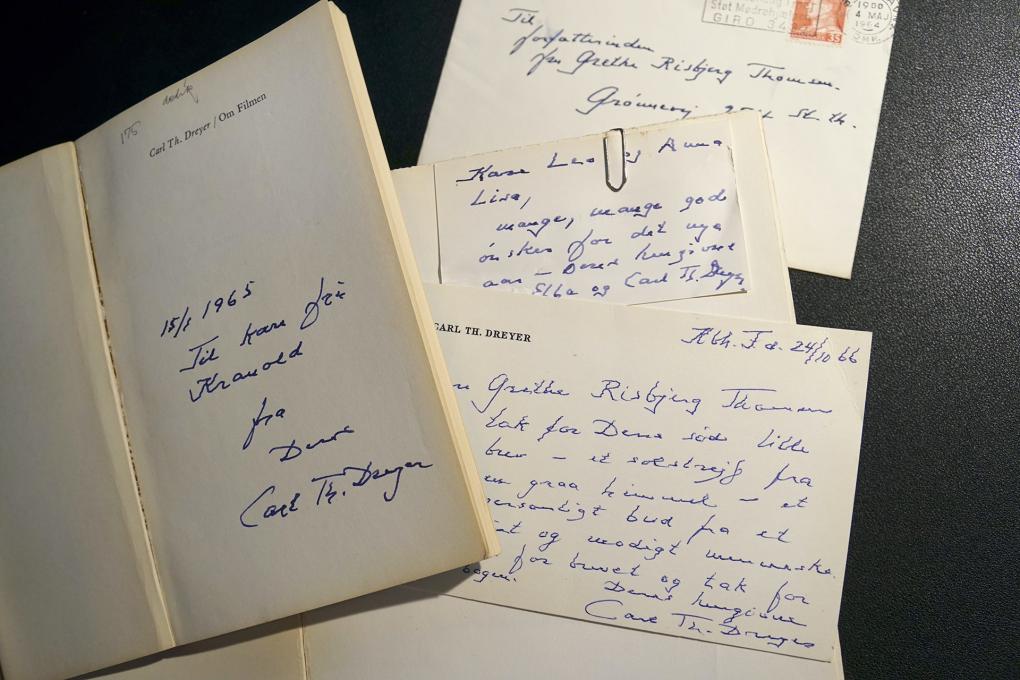

In the time that followed, my Dreyer-related efforts were all about watching his films. ‘Just’ reading about them was not quite enough. Unlike today, where these films are readily available on DVD, Blu-ray and can be rented digitally on Blockbuster.dk, it was difficult to get to watch them back then. Eventually, however, a melange of worn VHS copies and a few special screenings at the Cinematheque had enabled me to enjoy The President, The Passion of Joan of Arc, Vampyr and Day of Wrath. I was not disappointed. The old man on the cover of the book turned out to entirely meet every expectation so inexplicably created in me. My preoccupation with Dreyer’s films also quickly prompted a greater interest in Dreyer as a person. How did this small, cautious man, more reminiscent of an office clerk than an artist, create these dramas, this beauty and mystery? It remains a mystery to me.

The Collector

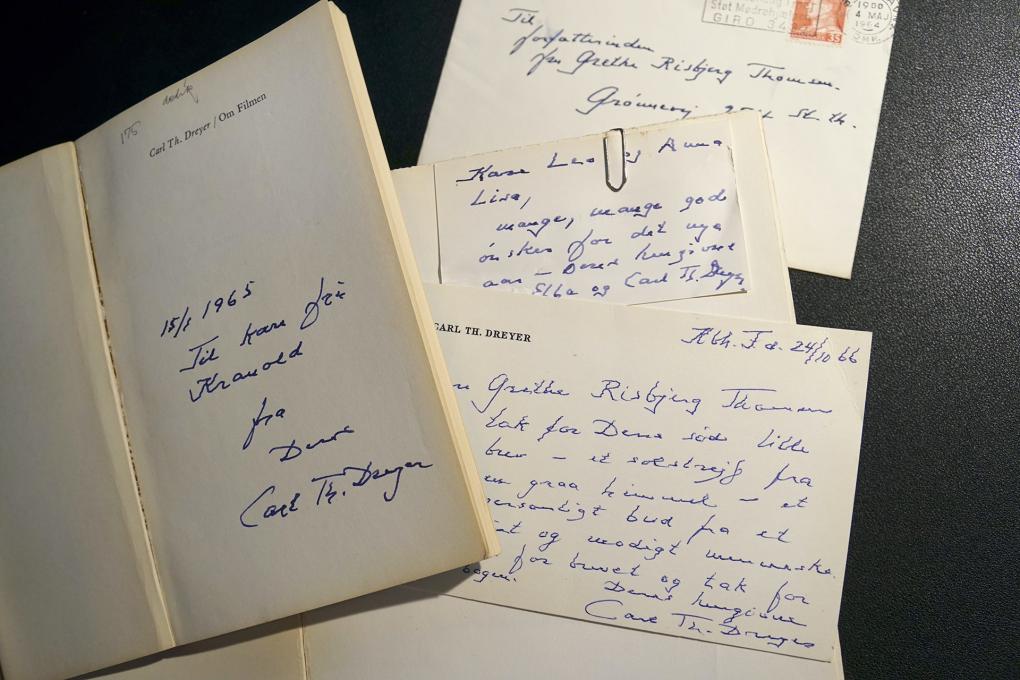

My mother was an antique dealer, and throughout my childhood I have been taken to antique stores, attended countless auctions and ploughed through flea market after flea market. Accordingly, I was a trained collector and sniffer-out of treasure even as a child, and now I flung myself, with wild abandon, at the task of tracing things, books, letters and other objects associated with Dreyer. The treasure hunt was on, and I was raring to go! However, it soon turned out to be rather heavy going. Sniffing out things that had passed through Dreyer’s hands proved more difficult than anticipated. The second-hand bookshops could do no more than inform me that it had been years and years since they last had any books with Dreyer’s handwritten scribbles inside. Even so, a mixture of sheer tenacity and countless visits to second-hand bookstores coupled with the aid of Ebay and Danish weekly printed classifieds let me build an ever-growing collection of books with dedications from the master. These are primarily brief, friendly and formal greetings. So while the collection takes up a lot of shelf space, it cannot lay claim to any great significance in terms of its content.

WHAT?!

One day, after many years of sloughing through shallow waters as a Dreyer collector, an opportunity suddenly arose to make an exciting new acquisition.

By virtue of my day-to-day work as a photographer and organiser, I was in the process of producing a documentary on the creation of Dreyer’s last feature film, the much-debated and little praised Gertrud from 1964. In that connection, I got in touch with Casper Tybjerg, an associate professor, film historian and Dreyer specialist. Having never met Casper before, I of course took the opportunity to ask if he himself owned any Dreyer ‘things’. Perhaps he had a book with a Dreyer dedication in it that he might just be willing to sell to me.

To my great disappointment, Casper told me that he was not a collector at all, which was also the reason why he had said ‘no’ to buying Dreyer’s old desk when it was offered to him a few months previously. WAIT, WHAT?! Forgetting all about the interview I was actually there to do, I immediately asked who had offered him the table. It turned out to be Mouschka Drouzy, daughter of Martin Drouzy, the man behind the book that had caught my twelve-year-old eye in that bookshop more than twenty years ago.

Why won’t she text me back?

When my afternoon with Casper was over, and the interview had been completed despite all distractions, I went straight home and sent a text message to Mouschka Drouzy with lightning speed. I stated, simply and bluntly, that I was willing to crawl over broken glass to be allowed to buy the desk from her. Having sent the text at 20.03, all I could do was to pace the room restlessly until she (hopefully) answered. What seemed like an eternity went by, and many thoughts flew through my head: ‘Why doesn’t she answer? Did I say something in the text that offended her? Was I too eager? Should I send her an email instead?’ Pliiiiiing! Finally, exactly 1 hour and 43 min. later, a text showed up on my screen. Mouschka had sent a reply.

I skimmed the long message for an answer to my question; would she sell me the desk or not? Without stating so directly, her response clearly indicated that yes, I could buy it. My bliss was assured. Almost. For there was one snag, Mouschka wrote: the desk was currently stored in her grandparents’ old house in Sweden, and what is more, it was kept at the very back of a room filled to the brim with large pieces of furniture. Topping off this litany of challenges to be overcome, she also informed me that it had taken two burly movers several hours to shift around all that furniture. I had to assert, with great self-confidence, that it would be no problem at all for me and a friend to dig out the desk. We had a deal.

The rescue

On 20 October at 14:00 the rescue mission began. Now, the desk was to be returned to Danish soil. The friend who was supposed to help was eventually replaced by my wife, and with the children safely dropped off at my mother’s, we set out on the Øresund train up through Scania and Halland, to Halmstad in southern Sweden. Here we were picked up by Mouschka in her red van and travelled on through hilly landscapes, into fairy-tale moss-covered forests, across rippling streams, all the way to an old and dilapidated wooden house on top of a hill, set in a pure idyll overlooking a large lake. Here, a major venture of modern archaeology was to be set in motion: the excavation of what for me corresponded to the tomb of Tutankamun: Carl Th. Dreyer’s old desk.

The lumber room where the table was supposed to be certainly matched Mouschka’s description.

It was filled with furniture of unwaveringly solid disposition. About three hours and a great deal of effort later, almost every piece had been taken out into the overgrown garden that enclosed the house. We had finally reached the back of the room. But where was the desk? ‘Is this it?’, I asked, pointing to something that might vaguely resemble a desk. ‘No, it’s much darker,’ Mouschka replied, a little puzzled. ‘I wonder if it’s here at all, I’m getting a bit anxious all of a sudden,’ she said with an uncertain laugh. I chose to tune out that remark entirely.

Fortunately, there was still one place that had not yet been searched. In the corner by the father’s old piano. If the desk was not there, there was quite simply no other place it could possibly be. And thank God, all our efforts had not been in vain. Underneath a blanket, Mouschka finally found it. Stood on its end, its bottom facing out towards us, was the Holy Grail: that is, Dreyer’s desk.

It had been tenderly covered in a blanket because this particular piece merited extra care. Immediately afterwards, my wife and I carried the table out of the house and down the uneven hill covered in slick autumn leaves, into the small van, and set out for Denmark.

And what a desk

The table, veneered in precious rosewood, was made by Valdemar Mortensen in Odense in the early 1960s. This was probably also when it found its new home in Dreyer’s flat in 81 Dalgas Boulevard in Frederiksberg, Copenhagen.

In his later years, Dreyer attracted a great deal of attention and interest as a public figure. It was very clear that the ‘ordinary’ Dane had become increasingly interested in him, especially after the success of The Word in 1955.

As the time drew near when Dreyer would finally have to follow up on this acclaimed and internationally award-winning work, and the preparations for Gertrud started, the media made regular reports from the world-famous Dane’s home.

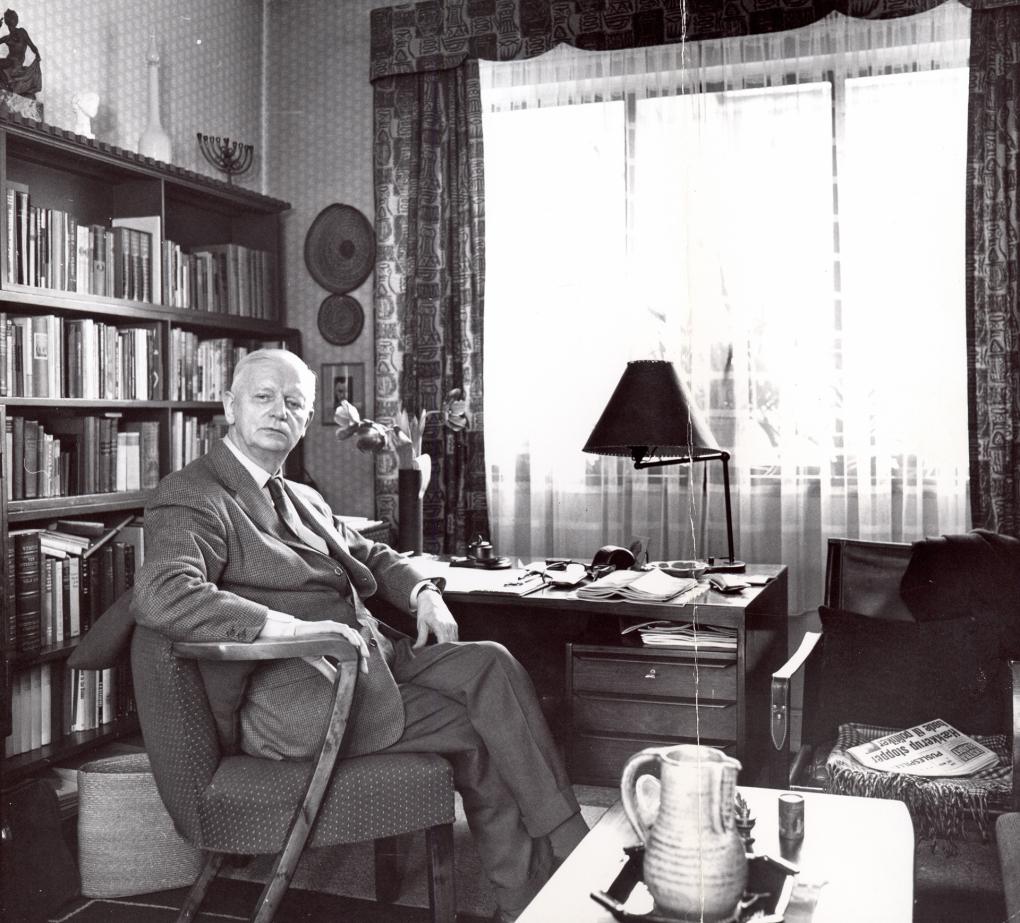

It was not uncommon for the popular Danish magazines Se og Hør and Billed-Bladet to publish several pages of articles about Dreyer. Television, too, ran brief features and longer broadcasts on him. The times were certainly different back then. Often, people were invited inside Dreyer’s study, right into the heart of the room, by the desk. Accordingly, the desk appears in a wealth of photos and TV footage.

For a home required to accommodate three adults, Dreyer’s flat was quite small, and so his so-called study served multiple functions. Looking at a floor plan of the flat, the room is described as a dining room, but in Dreyer’s time it doubled as his study and bedroom: a sofa bed to the right of the desk served as his bed; his wife and daughter shared the bedroom.2 While Dreyer had an office in the Dagmar Theatre in Copenhagen, granted to him in 1952, this was not where his creative work took place.3 When he was not selecting films for the repertoire at Dagmar, he spent all his time at his desk at home in Frederiksberg. In the words of Hans Christian Andersen: from there his world extended.

Dreyer’s death

Carl Th. Dreyer died in 1968 and his wife Ebba in 1977. Their daughter, Gunni, lived alone in the flat until her death in 1990. During these years, the interior remained virtually unchanged, and Dreyer’s study was kept intact like a sealed time capsule.4

During these years the writer and film researcher Martin Drouzy visited the Dreyer home regularly, especially in the time following Ebba’s death. He was among the few who regularly visited Gunni, both as a friend, but of course also as a writer, getting first-hand insight into the atmosphere that had surrounded the whole family and inspiring him to write his comprehensive biography about Dreyer. After Gunni’s death, Drouzy was among those who showed up in the flat in Dalgas Boulevard when it was time to break the seal and settle the estate. However, it appears that the proceedings were rather chaotic: ‘Almost the entire contents of the flat, its furniture, things, books, reproductions, objects, were put up for sale at auction, and it was impossible for me to intervene. Second-hand shops and booksellers bought in bulk, at ridiculously low prices, all those things that had formed the framework of Dreyer’s life or been the tools of this trade. The only piece of furniture I was able to save by acquiring it myself was the rosewood desk on which Dreyer had written his last manuscripts’. Martin Drouzy.5

Great expectations

The desk remained in Martin Drouzy’s possession until his death in 1998, after which it passed on to his daughter Mouschka, who for many years designed jewellery at it.

She is convinced that it holds creative power. Indeed, after the desk was sent away to Sweden for storage about a year ago, her production of jewellery ceased immediately.

Back on Danish soil, the table is safe and well here with me, and of course these lines were written on it. Now, I just look forward to being on the receiving end of any creative powers of inspiration that might radiate out of its venerable grain. The expectations are great.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank

Cathrine Rej – DFI – Katja Rie Glud – Casper Tybjerg – Mouschka Drouzy – Janne Drouzy – DR – Else Kjær – Tine Therese Bødker Sørensen – and others

Notes and sources

1. At the time of writing, the second-hand bookshop still exists in Elmegade in the Nørrebro district of Copenhagen.

2. Floor plan of the flat after the original drawing from the property management company.

3. Dreyer had a desk in his office at the Dagmar Theatre. At one point, it came into Lars von Trier’s possession. It has since changed hands again, but still exists.

4. Dreyer’s study makes an appearance in Michelle Porte’s documentary ‘In Search of Carl Theodor Dreyer’ (INA, 1987). It is clear that the interior has not changed since Dreyer’s death.

5. "Du skal ære din hustru, Dreyer og hans familie" (Master of the House; Dreyer and his family). Kosmorama # 215, 1996. As told by Martin Drouzy to Eva Jørholt, translated by Albert Wiinblad. In Danish.

Daniel Bødker Sørensen | 10. March 2021